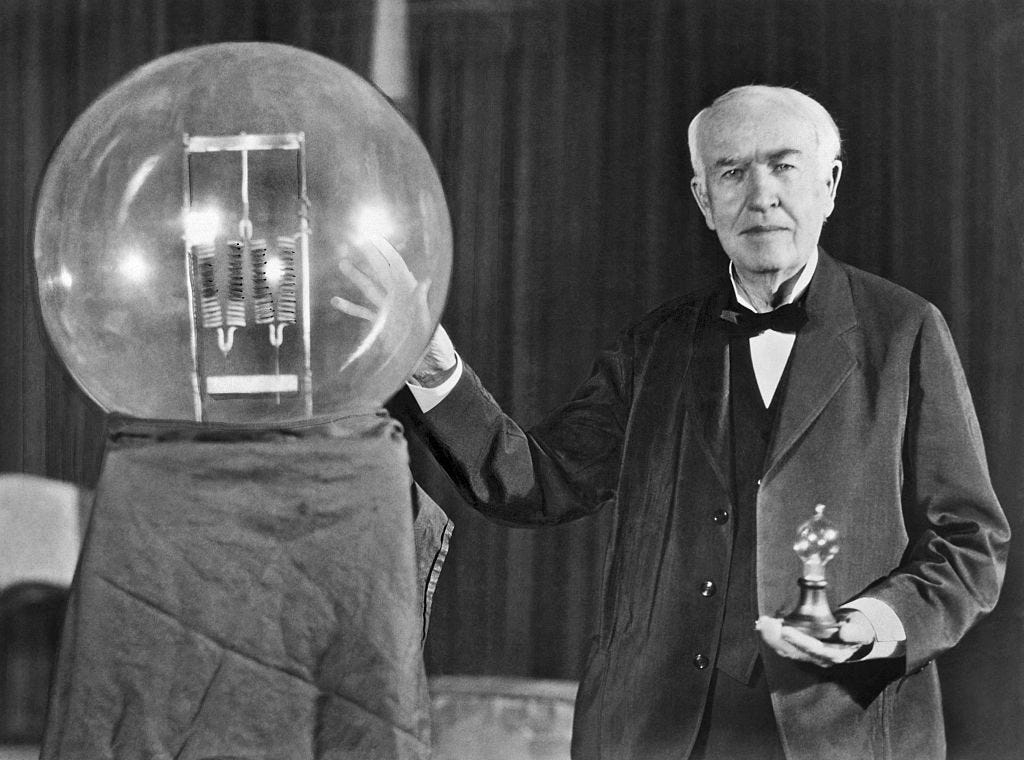

Thomas Edison: American Inventor

The life story of the famous Father of the Lightbulb.

Thomas Edison was one of the world’s greatest inventors. Everyone has heard his name, and their lives affected by his revolutionary inventions. Although best known as the Father of the Lightbulb, this famous American inventor made significant contributions to sound technology, cinema, branding, and countless other domains of modern life. Here is the enlightening story behind the glorious Ohioan inventor and Gilded Age titan, Thomas Alva Edison.

Early life

Edison was born in 1847 in Milan, Ohio. He was raised in Port Huron, Michigan after the family moved there in 1854. From an early age, he was driven by ambition. By his own recollection, Edison was curious to the point of being mischievous. On one occasion, the young boy sat on a neighbor’s goose eggs in an effort to hatch them. Another time, young Edison set a barn on fire just to see what would happen.

Thomas received a mere three months of formal education. He spent the carefree afternoons of his childhood reading through the library, and obsessively conducting chemistry experiments in the cellar. Money was tight. To finance his curiosity projects, Edison went to work at the age of 12. He took a job as a newsboy on the train that ran daily between Port Huron and Detroit.

Telegraphy

New technology was radically transforming and nationalizing the United States. Railways and telegraphs provided an unprecedented level of communication and connection; they were the social media of their day. Telegraphy consisted of sending information along copper wires at the speed of light. He was amazed by this technology. He taught himself Morse code, and he practiced sending and receiving messages for up to 18 hours a day. This hobby eventually landed him a job as an operator at the age of 15, in 1862.

By this time, Edison was already beginning to lose his hearing. But in the world of telegraphy, it was a blessing in disguise. It numbed his ears to the incessant noise of the machines. Thomas’ deafness made him more introspective and a clearer thinker. He often felt alone, even when other people were around.

Edison worked as a press operator for five years. He deciphered dots and dashes of news reports, as they came in over the wires. But after a while, he grew bored of the job. He took the night shift, which allowed him time to read and experiment. He began to tinker with the telegraphy equipment.

Lacking much formal education, Thomas Edison received much of his training at his telegraphy job. Telegraph offices were schools of electricity. He learned about this mysterious natural force, and how it could be used for human benefit. Over time, Edison developed a self-image as an inventor. He resigned the telegraphy job in 1869, and moved to New York on borrowed dollars. He had dreams of pursuing inventing—his lifelong hobby—as a full-fledged career.

For the next several years, he bounced from one business partnership to another. He often produced telegraphic gadgets on a contractual basis. Sleep was not something he cared about. Edison manufactured all sorts of variations of telegraphic devices. Some were automated. Others were printed. Multiplex telegraphs were capable of sending multiple messages at the same time, on the same wire. The booming telegraphy industry responded well to Edison’s innovative endeavors.

Menlo Park

By the early 1870s, Edison already had several telegraphic patents to his name, and enough money to finance his dream laboratory at Menlo Park.

Menlo Park was a great risk for Thomas. But he did it because of his creative vision. He wanted to be a great inventor. This was a revolutionary idea, and a very unorthodox life choice. He listened to his heart, and it paid him handsomely. Thomas met the love of his wife, a beautiful woman named Mary, in 1871. The couple married shortly thereafter. They had two kids, Marion and Thomas. He affectionately called them “Dot” and “Dash,” respectively.

It was 1876, and Edison was ready to work. He assembled a small cadre of technical experts and assistants, many of whom he had worked with for years. Edison moved his young family into a spacious house, just down from Menlo Park. Thomas, who was often busy with his work, rarely had time for his family, apart from Sundays. Menlo Park was a laboratory hard in toil. As many as a dozen men were working at a given time. Edison sought to produce a minor invention every ten days, and a large invention every month.

The Centennial Exposition opened on May 10, 1876 on 236 acres of land in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. It was America’s debut as the world’s leading industrial powerhouse. One item displayed was a steam engine capable of running hundreds of machines simultaneously. Another was an elevator that climbed eight stories. Another invention was a battery-operated pen. By this time, it was clear to the world that America trafficked in the trade of genius.

Bell’s telephone

Thomas Edison’s all-too-familiar world of telegraphy was revolutionized by yet another ground-breaking invention: Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. Bell’s ingenious device converted sound waves into electrical signals. It promised to replace the impersonal dots and dashes of telegraphy with the warm sound of a real human voice. It was truly magical.

Realizing the enormous potential, Western Union turned to Thomas Edison to investigate into Bell’s telephone. In truly American fashion, Edison was enthralled by the prospect of competition. He lived and breathed not for the cash, but the opportunity to outcompete his professional rivals. Bell, who was college-educated and bankrolled by his future father-in-law, was the yin to Edison’s yang. Bell had no respect for Edison, feeling little more than contempt. This only motivated Edison even more to overcome Bell.

It would take months for Edison to design a device that could outshine Bell’s telephone. He created a carbon button transmitter, which could carry sound over longer distances. This turned the telephone into a commercial viable product. In this process, Edison stumbled upon an invention that would change his life forever.

Phonograph

By the summer of 1877, Edison experimented with telegraphic devices that could leave impressions on paper. He was trying to figure out a way to do with this, but with a telephone. He had the basic idea of the vibrating diaphragm from the telephone, and decided to add a needle in the middle. He put a strip of paper in the middle, and as a person speaks, impressions were recorded on it. Edison drew up some sketches for this new device, which he called the phonograph. In Greek, this means “writer of sound.”

After testing various designs, Edison decided upon one where a sheet of foil was mounted on a hand-crank cylinder. The first words he tested were those of the classic nursery rhyme “Mary Had A Little Lamb.” It became the world’s first-ever recorded sound.

Scientific American, the nation’s leading publication for science and technology, began to aggressively promote the new invention. Reporters flocked to Menlo Park to witness Edison’s miraculous invention. He became an overnight sensation.

All-American inventor

Edison cultivated his larger-than-life inventor’s persona to go along with his inventions. He demonstrated his devices wearing a lab coat. He offered slices of pie and cigars to his onlookers. He loved to crack jokes, as he unveiled the mysteries of science at Menlo Park. His answers to questions were always insightful and thought-provoking.

Edison’s personality matched the archetype for the all-American inventor genius. He came from humble origins. He was self-taught. He was a charismatic storyteller. All of these qualities endeared him to the press, which he skillfully used to promote his inventions. Edison became the personal embodiment of the ideals of the American Gilded Age, combining commercialized entrepreneurship with a romanticized lust-for-life curiosity about the natural world.

In 1878, Edison demonstrated his phonograph before President Rutherford B. Hayes and Congress. A portrait was taken by celebrated photographer Matthew Brady. By then, news of Edison’s phonograph reached international ears. He received dozens of fan letters each day.

Age of Electricity

Artificial lighting has existed for thousands of years. Before the lightbulb, gas light was common. It was a terrible technology for many reasons. It sucked the oxygen out of the air, and overheated rooms. It produced acidic vapor. Accidental leaks led to accident death by asphyxiation.

Edison recognized that, if he could create a new light that was safer and cleaner, it would change the world. By September of 1878, Edison began his work to create a new form of artificial indoor lighting.

For the previous 70 years, electricity had powered American life and industry. But before Edison, the only commercially viable product that had been produced was the arc light. It was a method that forced a current to jump between two carbon rods. The light was so blinding, that it could only be used outdoors or large public spaces. People could not bear how obnoxiously bright it was. The only alternative to the arc light was the incandescent light bulb, which was first patented in 1841. But it was still not viable, even after four decades.

After just a couple days of experiments, Edison felt he knew the answer. He grabbed headlines in the press, boasting that he had found a way to produce an electrical system that would be cheaper and safer than gas. Gas stocks plunged, and financiers flocked to Edison. The Wizard of Menlo promised that, within a matter of weeks, he would set Manhattan aglow with incandescent lighting.

But weeks turned into months, and then years. The public grew increasingly impatient with Edison’s outlandish prognostications. He was denounced as a stock manipulator who merely got lucky with the phonograph. Edison was deeply angry at these criticisms, because the inventor and his associates were working tirelessly for their goal. It unnerved his Wall Street investors, notably J.P. Morgan.

Finally, by 1882, Edison’s grand project was complete. On September 4, Edison’s electrical power system was switched on in Pearl Street, New York City. It successfully lit up a square mile of Lower Manhattan.

Second marriage

But the light of Edison’s life was extinguished after his wife died in 1884. A couple of years later, the 39-year-old Edison married the 20-year-old Mina Miller, the daughter of an Ohio industrialist. Thomas was madly in love with her. He taught his new wife Morse code, which allowed them to communicate privately. He proposed to her through telegraph. With marriage came a new house, a grand mansion of 23 rooms in West Orange, New Jersey. Edison had three more children: a daughter, and two sons. Now that his marital life was settled, Thomas was eager to return back to work.

AC/DC

In 1887, Thomas Edison founded a new laboratory on Main Street, just down the hill from his new home. The new lab was ten times larger than Menlo Park. It was full of machine shops, chemical rooms, libraries, and bizarre paraphernalia. But despite Edison’s surge of creativity, there were plenty of other inventors who posed fierce competition.

By the late 1880s, the rivalry between Edison and Bell renewed. Bell had transformed Thomas’ phonograph by adding a wax surface. This was the graphophone. Edison was deeply annoyed. He denounced Bell and his associates as “pirates.” He vowed to create an even better version of the phonograph.

Other inventors were now experimenting with another type of electrical power: alternating currents. In 1884, Pittsburgh entrepreneur George Westinghouse began buying up patents from electrical investors in America and abroad. The AC technology of Westinghouse and others could deliver electricity several hundred miles from the generating station. But Edison’s DC system could only deliver within a mile or so from the generator. Edison’s system now seemed obsolete.

Edison had 121 stations. By just one year into business, Westinghouse had 68 stations. His competitors offered cheaper, better products. Thomas’ friends begged him to start using AC, but he refused. He lacked the mathematics needed to handle AC technology. Unable to out-invent his competitors, Edison now embarked on a campaign to discredit them. He tried to convince the public that AC was unsafe. But it was no use. By 1890, it was clear that AC was the wave of the future. Edison’s financiers abandoned him, and his name was dropped from his company. It was now called General Electric.

Iron ore

Frustrated, Edison vowed to embark on an even greater project than electricity. By the 1890s, America’s building industry was in full swing. For two decades, railroads and bridges were rapidly constructed. All of this construction dependent on steel and iron ore. Edison saw a new opportunity for invention. He wanted to find a new process for extracting iron from low-grade ore. His plan was to use dynamite to break up mountains into giant boulders. He would then caulderize the boulders in giant, interlocking drums that would crush them into bubbles. Iron would then be extracted by magnets out of a very fine sediment. He intended to automate this entire process.

Edison’s mining plans were dashed after a new source of high-grade ore was discovered in the Midwest. He finally admitted defeat in 1898, after wasting ten years and $2 million of his own money. But he didn’t care. It was the fun that mattered.

Film

Edison built the world’s first movie studio, called the Black Maria, in winter of 1893, just outside his main laboratory at West Orange.

In 1894, the American inventor filmed a sharp-shooting woman named Annie Oakley. Annie was performing her live act, firing away at tiny glass balls—all as Edison’s latest invention captured the action in real time. The device was an electrically-powered camera, which recorded motion. It was the first of its kind in the United States.

Edison’s idea for the movie camera came six years before, in 1888. It was sparked with a conversation he had with British photographer Edward Muybridge. Muybridge was known for his photos of animal motion. He used a revolving disc with images, which looked like what we would now call motion pictures. Edison attended one of his lectures, and he thought about combining the phonograph with Muybridge’s moving pictures to create talking pictures. This was the genesis of film. Edison came up with the kinetograph, a recording device whose name in Greek means “writer of motion.” It promised to do for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear. Further inspiration came during Edison’s visit to Paris in 1889, where he first encountered chronophotography.

The world was immediately fascinated by Edison’s cinema. People paid a nickel to watch his short films. But soon enough, the novelty wore off. Edison realized the problem. Moving from machine to machine really ruined the viewing experience. So his friends urged the American inventor to produce a projection device. Edison was reluctant, fearing that such an invention would completely undermine his kinetograph. But this proved to be a short-sighted move. Edison was beaten at his own game when, in 1895, the French Lumière brothers invented their own projector system. It was a massive hit in Paris. That same year, another invention called the fantascope was unveiled in Atlanta, Georgia. Larger-than-life figures began to appear onscreen. It became clear that projectors were the future of motion pictures. Edison decided to convince the inventor of the fantascope to sell off his rights to him. Edison unveiled his own version, the vitascope, in 1896. The American movie industry was born.

Final years

By 1911, Edison’s company was a global phenomena. He aggressively promoted his products using his charismatic inventor image. His face, name, and signature graced all of his products. Beyond his inventions, Edison played a pivotal role in the history of American branding. Edison suffered misfortune when his phonographs were burned in a city fire in 1914. Damages were up to $3-5 million. Undaunted, the 67-year-old Edison simply laughed. He continued to enjoy his national celebrity status.

In 1926, at the age of 79, Edison officially retired. He took up permanent residence in Fort Myers, Florida. By this time, he had over 1,000 patents in his name. Edison embarked on yet another project, this time to cultivate a domestic source of rubber. Almost completely defeat, and suffering from kidney disease and chronic indigestion, the elderly Edison stopped eating. His diet was limited to cigars and a pint of milk every three hours. He returned to West Orange in 1931. His health waned, and he was left bedridden. Edison died on October 18, 1931, at the age of 84.

Legacy

Thomas Edison left an indelible mark on human history. He literally illuminated a world of darkness. Before him, most people did not enjoy the luxuries of industrial life. Even the basic luxury of indoor lighting was barely around. Lighting was restricted to kerosene lamps. There was no recording of sounds, voices, or motions. By the end of Edison’s life, he had left behind a luminescent modernity, characterized by an exciting and optimistic technological progress. His inventions were too numerous to count, and his distinguished career demonstrated that anything could be changed and controlled. He was not just a first-rate inventor, but also a charismatic celebrity and entrepreneurial businessman. Edison’s electrifying dynamism and boundless ambition reflected the great nation that he lived in, and whose ideals he personally embodied. Today, Thomas Edison remains an enduring American symbol of self-invention, modernity, and creative exploration.

Learn More