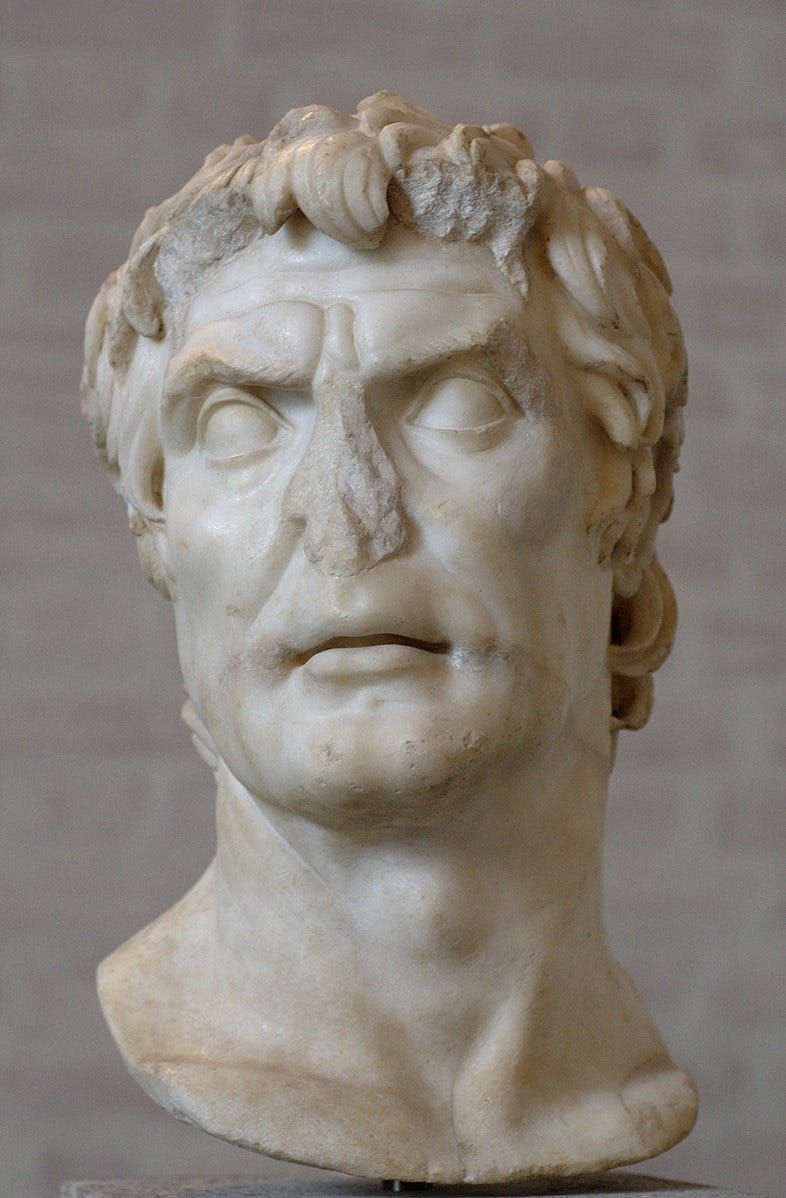

Sulla: Rome's First Dictator

How an ambitious Roman general plunged the Republic into a civil war.

Before Julius Caesar, there was Sulla. Sulla was Rome’s first dictator, and he established the dangerous precedent of the military marching on the Eternal City itself. He became the first person in the Republic’s history to seize power by force, and instigated what became a bloody civil war in the Late Republic. Despite his questionable moves and authoritarian reign, Sulla nevertheless was a source of fascination and admiration even among his enemies.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla was born in 138 BC, in the city of Puteoli, near Naples. He came from one of Rome’s oldest patrician households, the gens Cornelia. By Sulla’s time, the family had lost most of its former prestige. According to Plutarch, our primary source about Sulla’s life, Sulla grew up in cheap lodgings only marginally better than those of an ordinary freedman.

As a young man, Sulla loved to carouse and drink wine. He kept the boisterous company of actors and musicians. In order to improve his financial situation, Sulla often turned to offering sexual favors in his 20s. He was something of a gigolo to an old Roman widow, who in turn named the young man as her heir. Through the connections of his stepmother, the ambitious Sulla made his thunderous entry into the politics of the Late Roman Republic. He first served as a quaestor during the consulship of his future rival, Gaius Marius.

Jugurtha’s War

In 112 BC, Rome declared war on the Kingdom of Numidia, as retribution for their support of Hannibal during the Punic Wars. This conflict became known as the Jugurthine War, named after Numidia’s King Jugurtha. It was hardly the walk-in-the-park that the Romans had hoped for. Four consuls were defeated and humiliated, until Gaius Marius was sent over there in 107 BC. Marius appealed for aid from a Roman ally named King Bocchus, who ruled over the nearby kingdom of Mauretania. Bocchus agreed to assist Marius, in exchange for the western half of the spoils. The Romans ultimately prevailed, with the Numidian King being paraded and executed in Rome in 104 BC.

Cimbri War

The Romans declared war against a Germanic confederation of tribes, led by the Cimbri, which had migrated into Roman territory. The Cimbrian War saw many humiliating Roman losses, including the ill-fated Battle of Arausio, Rome’s worst defeat since the days of Hannibal.

Marius again was tasked with vanquishing the enemies of Rome. He was permitted by the Senate to do whatever necessary to stop the Germanic tribes from marching into Rome. Despite tensions between the two men, Marius and Sulla worked together to push back the tribal invaders. Together, the two men turned the war in Rome’s favor.

In 102 BC, Marius received the consulship for the fourth time. Sulla worked behind the scenes to shore up his own power. His generosity to the Roman legions won him strong support from the military. This enabled Sulla to embark on a successful political career in 97 BC. Sulla campaigned in Cappadocia against King Mithridates VI, and returned to Rome by 93 BC.

Social War

Rome’s next major conflict was the Social War, fought against its Italian allies, collectively known as the socii. The allies demanded Roman citizenship, but when their request was rebuffed, they revolted against Rome in 93 BC.

Sulla fought against the Samnites and other Italic groups in southern Italy. He besieged the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, before capturing the enemy capital at Aeculaneum. His greatest victory occurred at the Battle of Nola, where he overwhelmed an army of 20,000.

The war ended in Roman victory in 87 BC. Sulla was awarded by being elected consul in 88 BC, at the age of 50. He received the Grass Crown, one of Rome’s highest military honors.

A civil war

King Mithridates returned with a vengeance, annexing Cappadocia and the Roman client state of Bithynia by 88 BC. He engaged in a genocidal campaign, known as the Asiatic Vespers, against all Romans and Latin-speaking Greeks. Between 80,000 to 150,000 people were harmed.

The 70-year-old Sulla was given a prestigious military command, much to Marius’ frustration. Marius engaged in behind-the-scenes politics, in order to get Sulla’s command removed. Sulla was enraged. The tensions between the two men had been growing for decades, and it had reached a boiling point.

In truly unprecedented fashion, Sulla did the unthinkable: he took 30,000 troops and marched on Rome. He and his army captured the Esquiline Gate. As they marched through the streets, Sulla and his men were pelted with rocks by the enraged, unarmed masses of Romans, who had taken refuge on the rooftops of their homes. Sulla responded with brutality and force. He ordered their homes burned to the ground.

Marius knew he was in serious trouble. In a last-ditch effort, he asked slaves and gladiators to take up arms on his behalf. But it was in vain. Marius was forced to flee the city, leaving Sulla as Rome’s new leader.

Rome’s dictator

Now the new ruler, Sulla summoned the Senate. The dictator enacted a death sentence against Marius and his close supporters. To show the Republic was still free, Sulla allowed one of his political opponents, a man named Lucius Cinna, to become consul. It turned out to be a foolish move.

As Sulla left Rome to fight Mithridates, Cinna conspired covertly with Marius, who was in exile in North Africa. In 87 BC, Marius returned from exile with an army and recaptured Rome. But the Romans didn’t realize that Marius would be even more cruel than his adversary Sulla. Five days of chaos, death, and violence broke out. Marius and Cinna decapitated many of Sulla’s supporters, and displayed their heads near the Senate.

Amid the violence, the distinction between friends and enemies broke down completely. Marius’ rapacious supporters went after anyone whose property they wanted to confiscate. In 86 BC, Marius and Cinna ran for consul. Due to their heavy-handed, authoritarian tactics, the two men won the election. Two weeks later, Marius died of natural causes.

Fighting Mithridates

As all of this drama unfolded in Rome, Sulla was still away fighting King Mithridates. He began by fighting against the king’s Greek allies. At this point, the Greeks had been under Rome’s power for only a few decades. Many Greeks were eager to support a Hellenistic revolt against their Roman occupiers. When Sulla arrived with his fearsome legions, the Greek allies abandoned their cause and restored relations with Rome.

One exception was Aristion, the tyrant king of Athens, who longed to restore the city’s former glory. He remained allied with Mithridates, hoping to restore the Hellenistic world. The city-state became Sulla’s first target, as he besieged Athens and its nearby port-city of Piraeus. This stopped food shipments from reaching Athens. It was ruthless, but effective. The city was strangled out, struck by famine, death, and even cannibalism. By early spring of 86 BC, Athens came back under Rome’s grip, and Aristion was executed.

Mithridates released that the war was lost, so he made peace with Sulla. He agreed to renounce his claims over Bithynia and Cappadocia. He paid 2,000 talents to Sulla, and gave him 70 ships. In exchange, Sulla agreed to recognize the king as a legitimate ruler, elevating him to the favored status of a Roman ally.

Second civil war

Sulla returned back to Rome, where he again marched on the Eternal City. He clashed against a new alliance, led by Marius the Younger and Carbo. In 84 BC, Cinna was killed by his own men, in a mutiny.

Sulla arrived in southern Italy in 83 BC. His first battle took place near Capua, which was a decisive victory. One by one, he defeated the consular armies of the Senate.

In April of 82 BC, Sulla crushed the forces of Marius the Younger. In November, another decisive battle was fought outside the walls of Rome. The Battle of the Colline Gate nearly ended in Sulla’s defeat, but it saved by the intervention of Crassus. Crassus managed to rout the right flank, as Sulla struggled against the left one.

Having subdued his enemies, Sulla was declared dictator by the Senate. He showed no mercy to his enemies, executing and banishing them. Pompey and Crassus, who had participated in the war on Sulla’s behalf, were generously rewarded by the Roman dictator. He gave himself immunity, and became consul. After serving his term, Sulla finally stepped down. He gave a passionate speech in the Forum, explaining his actions to the Roman people. Sulla assured the Romans that he did not want to be a tyrant, but that it was forced upon him by circumstances. Even anti-Sulla writers, such as Cicero, Plutarch, and Appian, had to admit some admiration for the man.

In 79 BC, Sulla retired to his villa in Naples, where he penned his memoirs. Spending the rest of his days in the company of actors and musicians, the Roman general died the next year, in 78 BC, at the ripe old age of 60. He received a public funeral with honors. His tomb was placed at Rome’s Campus Martius, which proudly displayed Sulla’s motto of life: “No better friend, no worse enemy.”