Rome vs. Carthage: The Road to War

How two of the ancient Mediterranean's superpowers came to clash.

The Punic Wars determined the course of the Mediterranean’s history. It was an existential clash between two powers: Rome and Carthage.

Rise of Rome

At the dawn of Rome’s power, Italy was not yet a unified state. In fact, that did not happen until the mid-to-late 19th century AD. The young Roman Republic expanded against its Italian neighbors, including the Etruscans, the Umbri, the Samnites, and many other smaller Italic tribes. These territories were absorbed and incorporated into the Roman Republic, bound by treaties with Rome. In exchange for their autonomy, the allies promised to cede their foreign affairs to Rome. The Romans incorporated the armed forces of these Italic states into their own, resulting in a near-endless supply of manpower for the Republic. The Italian allies were granted shares of Rome’s spoils of war, giving them a stake in Rome’s aggressive expansionism.

Having conquered central Italy, Rome turned its attention to the Greek states of southern Italy. In 280 BC, provoked by border skirmishes with Rome, the city of Tarentum appealed for aid from the Greek kingdom of Epirus, located across the sea in modern-day Albania and Greece. Ruled by Pyrrhus, a seasoned military mercenary, the Kingdom eagerly obliged Tarentum’s request. Pyrrhus and his men crossed the sea, where they confronted the Romans at Heraclea. Facing a professional army for the first time, the Romans were defeated, but only narrowly. Pyrrhus pressed onward with another hard-fought victory at Asculum later that year. In the process, the Romans inflicted high losses on Pyrrhus’ army. Hence the term “Pyrrhic victory.” On paper, Pyrrhus was winning the battles, but he wasn’t able to resupply his army the way that the Romans could. The losses were too much for him to sustain.

Pyrrhus decided to divert the war to Sicily, where he fought against Carthage. He returned to southern Italy in 275 BC, where he fought a bloody stalemate against the Romans at the Battle of Beneventum. Lacking the manpower to continue the war, Pyrrhus abandoned his allies and returned to Epirus in 272 BC. Tarentum fell, securing Rome’s control over all of southern Italy.

As Rome expanded, so did its institutions. By the 3rd century BC, Rome had created a stable government, which would continue intact for centuries. The Republic was led by two consuls, elected each year, who acted as Rome’s chief executives. Consuls were tasked with commanding Rome’s armed forces. There was also the Senate, in charge of political decision-making. The Senate advised the consuls, and managed Rome’s treasury and foreign policy. The Senate was further responsible for discussing and passing decrees. The Senate itself was balanced by a number of popular assemblies, which gave legislative power to the Senate’s decrees. The assemblies elected consuls and other offices, and had the power to declare war. Decisions were heavily weighted toward the wealthy, and it was an oligarchy.

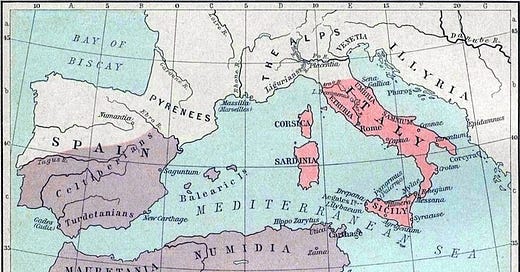

By 270 BC, Rome had control over all of central and southern Italy. Rome’s ambitious wars were funded by its conquests. The Roman legions were able to defeat their enemies by waging long wars of attrition, thanks to its endless supply of manpower. Aristocracy and commoners alike endorsed Rome’s military adventurism. Generals vied for triumph and glory.

Carthage’s Empire

At the same time as Rome’s conquests, Carthage was consolidating its own influence throughout the Western Mediterranean. Located on the northern coast of modern-day Tunisia, Carthage was one of many Phoenician colonies sprinkled across the Middle East. The Phoenician cities of Arwad, Byblos, Sidon, and Tyre—all based in modern-day Lebanon—controlled a vast Mediterranean maritime empire. The Phoenicians reached their apogee by the 9th century BC, when they became a challenger to the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Very little is known of Carthage’s early history, which is difficult to disentangle from mythology. Archeological evidence, based on carbon 14 dating, suggests that Carthage was founded as a colony of Tyre. By the 8th century BC, the flowering colony of Carthage had grown independent of its mother state of Tyre. Over the next 300 years, Carthage continued to expand across North Africa. It engaged in trade with the other Phoenician colonies, including Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and Iberia. During the same period, Carthage forged ties with the various tribes of central and northern Italy, as well as the Greek colonies in southern Italy.

In 573 BC, the mainland Phoenician city-states lost their autonomy to the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Many of these cities were captured, and its overseas colonies. Carthage, on the other hand, continued to prosper. Situated strategically between North Africa and the islands of the Western Mediterranean, Carthage was now the largest of Phoenicia’s colonies. Throughout the 6th century BC, Carthage began to exert its influence aboard on the other overseas Phoenician colonies, forging a distinct Punic identity.

Beginning in the 5th century BC, Carthage expanded more aggressively to the east, making gains in Africa. They signed treaties with the Libyan tribes and local Numidian kingdoms. Sardinia became a major supplier of food to Carthage. Settlers from Carthage poured into Sardinia over the second half of the 5th century BC. Threatened by the Greek settlement of Syracuse, Carthage began to expand into western Sicily. By the 4th century BC, Carthage regarded the Western Mediterranean as an integral part of its territory. After defeating the Romans, Pyrrhus made further gains in the Punic territory of Syracuse in 278 BC. Within a couple years, Pyrrhus nearly wiped out Carthage’s control over Sicily. Lacking supplies to invade North Africa, Pyrrhus simply returned home to Greece. This allowed Carthage to restore its former control of Sicily. The stage was set for a conflict between Rome and Carthage over the disputed territory of Sicily.

By the early 3rd century BC, Carthage had ballooned into an enormous maritime empire. In addition to controlling the whole coast of Northern Africa, between Cyrenaica and to the edge of the Atlantic, Carthage controlled sections of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, the Balearic Islands, and southern Spain.

Rome and Carthage

Carthage had a similar political system to that of Rome. According to Aristotle, Carthage was an oligarchy, which ruled according to representative institutions. The most important were judges, called sufetes, which were elected two at a time. Unlike Rome, the judges of Carthage did not command armies. Separate generals were elected. Carthage also had a council of elders, which the Romans equated with their own Senate. There were also popular assemblies, just like in Rome.

Unlike the homogenous Roman Republic, Carthage’s overseas empire was a loose confederation of diverse peoples, united only by their common payment of tribute. Later on, in the Punic Wars, Carthage would have to rely on African mercenaries, since their citizens were exempt from military duty. Carthage had a much stronger navy than Rome. At the start of the Punic Wars, Carthage enjoyed a significant advantage in terms of fleet size and experience.

Outbreak of War

By 270 BC, the battle grounds were set. But a conflict did not appear imminent. Rome and Carthage were more often allies than enemies. They traded with one another. From the 6th to the 4th centuries BC, the two superpowers signed many treaties. The earliest of these was signed around 509 BC, when Rome was still a tiny city-state. It was a non-interference agreement, carving out spheres of influence for Rome and Carthage. Carthage pledged not to intervene in mainland Italy, while Rome was barred from trading with or invading North Africa, Sardinia, and Corsica. Later treaties were signed in 348 BC, as Rome expanded its dominion over central Italy. Another treaty appeared in 306 BC, after Rome’s second war against the Samnites. The treaty, whose existence was disputed by ancient authors, allegedly required Rome not to intervene in Sicily. A final treaty was signed around 278 BC, during Pyrrhus’ wars in southern Italy and Sicily.

In the lead-up to the Punic Wars, a conflict broke out in Sicily, caused by a group of mercenaries known as the Mamertines. After Syracuse was defeated in a war against Sicily, the city of Messina was handed over to Carthage in 307 BC. Upon the death of Agathocles in 289 BC, many of his mercenaries were left idle and unemployed in Sicily. Most of them returned home, but some stayed on the foreign island. When Syracuse’s tyrant, King Hiero, besieged their base at Messina in 265 BC, the Mamertines called for help from a nearby fleet from Carthage, which proceeded to occupy the harbor of Messina. Seeing this, the Syracuse forces retreated, not wishing to provoke Carthage. Uncomfortable under Carthage’s new protectorate, the Mamertines appealed to Carthage’s rival, Rome, for aid.

At first, the Romans did not want to aid the Mamertines, who were seen as unjustly stealing the city. However, unwilling to see Carthage expand into Sicily, the Romans begrudgingly entered an alliance with the Mamertines. In response, Syracuse allied with Carthage. As tensions grew between Rome and Carthage, the Syracuse-Mamertine conflict escalated into the First Punic War.