Rameses the Great was born around 1303 BC. His father came from a prominent aristocratic military family in northern Egypt, probably from one of the fortified cities of the Nile Delta. This man would later assume Egypt’s throne as Seti I. His mother was Tuya, also a member of the Egyptian nobility.

The Hittites

During the Bronze Age, powerful centralized states emerged in many parts of the Eastern Mediterranean. Greece was dominated by the Mycenaeans of the mainland, and the Minoans on the island of Crete. Throughout this time, literary and artistic societies emerged for the first time. In modern-day Turkey, the powerful Hittite Empire rose to prominence. Its capital was the city was Hattusa. Shortly before Ramses’ birth, the Hittites had begun its conquest of the Levant and Mesopotamia. It was Egypt’s dominant rival in the region. Further southeast were the empires of Babylon and Assyria. Both were rich, sophisticated, and engaged in international trade. Under Hittite control, gold and silver was mined in western Anatolia. Copper was mined in Cyprus in order to construct chariots, weapons, and utensils.

Egypt’s New Kingdom

Like the Hittites, the Egyptians were entering their own golden age. It was called the New Kingdom. Egypt enjoyed wealth and prosperity. The term “New Kingdom” was invented by scholars in the 19th century, although it is still widely accepted by modern Egyptologists. The New Kingdom of Egyptian history was an epoch of Bronze Age affluence that exceeded all preceding periods. The New Kingdom even outshone the Old Kingdom, when the Great Pyramids of Giza were constructed a millennium earlier. During the New Kingdom, the Egyptian pharaohs created a powerful government that was administered by viziers and scribes. Egypt maintained a massive military, thanks to developments in technology, such as chariots and bronze weapons. The centralized state of Egypt extracted more taxes from the people, and expanded its empire in all directions. More outposts were established down the Nile in Nubia, in what is now Sudan. The Egyptians annexed the territories of the Sinai peninsula, and northward into Canaan and modern-day Lebanon. The Egyptian Empire peaked around the 15th century BC, during the long reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III. He expanded the empire northeast to include parts of modern-day Syria and northern Iraq.

Ramses I

Around the time of Ramses’ birth, Egypt had recently stabilized after the revolutionary changes of King Akhenaten. King Horembheb managed to reverse those unpopular changes, restoring Egypt’s traditional religious and political institutions. However, he lacked a biological successor, so he chose his vizier to assume the throne after his death. This was Ramses I, who assumed the throne around 1292 BC. Ramses I was the grandfather of Ramses II. His rule ended with his untimely death a few years later. The elder Ramses was succeeded by a son, who took the name Seti I, in honor of the Egyptian god Seth, the god of war. During this time, the future Ramses II served as a prince regent. Over a decade of Seti’s reign, the Egyptian regime consolidated its control over Canaan and Syria. Ramses undoubtedly gained crucial military experience while campaigning with his father.

Ramses II

Ramses II acceded the throne on May 31, 1279 BC. He reigned for 66 years. This became an unprecedented Golden Age for ancient Egypt. Ramses began his reign by cracking down on sea pirates, which were threatening the prosperous settlements of northern Egypt. Forts were established to police the area. Additional forts were constructed in the disputed territories of Sinai and Canaan, in the northeast. New ships were built to patrol the waters of the Eastern Mediterranean. Watchmen posts were set up to warn the Egyptians of any impending raids. Ramses’ campaigns against the pirates culminated with a colossal sea battle. Egypt’s mighty navy prevailed over the enemy. This victory was commemorated by a stele, which still exists today. However, no other details are known with any certainty. Having secured the northern shores of Egypt and the Nile Delta, Ramses’ next objective was to reassert Egyptian control over Canaan and the rest of the Levant. Egypt’s economy boomed from the bountiful agriculture of the Nile, and the production of pottery and papyrus from cities like Thebes and Memphis. However, the most prosperous settlements of the region were Tyre and Sidon, which benefited enormously from trade with its imperial neighbors on all sides. Egypt’s ambitions in the Levant were countered by the mighty Hittites. The conflict between the two superpowers would characterize the bulk of Ramses’ reign. Ramses established a new capital in the northeastern Nile Delta in the 1270s BC. It was located near the modern town of Qantir. The new capital served a military function. Large workshops and factories were built to produce weapons, armor, and chariots. Ramses’ new capital became an administrative center for Lower Egypt. However, Ramses regarded the city of Thebes as the spiritual capitals of Egypt.

Conquest of the Levant

Ramses clashed against the Hittite Empire, ruled by King Muwatalli II since the mid-1290s. Early in his reign, the Hittite King exploited Egypt’s weakness by moving his capital southward into the contested Levant region. So the earliest years of Ramses’ rule in Egypt were spent campaigning northeastward from the Nile Delta. The first of the Great Pharaoh’s campaigns took place in 1275 BC. It established Egypt’s control over southern Canaan. Ramses then advanced further northward into the region, around the modern-day city of Beirut. There, he ordered a stele be erected at Nahr el-Kalb. The actual text of this commemorative monument has not survived. Ramses campaigned further against Amurru, a vassal state of the Hittites, in modern-day Syria. But Ramses abruptly ended his campaigning, which allowed the Hittites to restore their influence in the Levant.

Battle of Kadesh

The conflict between the Bronze Age empires of Egypt and the Hittites culminated with the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC. Kadesh was located on the banks of the Orontes River, in western Syria. The Battle of Kadesh was a landmark moment in military history. The armies involved were massive by the standards of the Late Bronze Age. It is the best documented battle of the second millennium BC. Both sides left behind extensive records of the battle, such as tablets, wall paintings, and inscriptions. It was an era-defining battle. The battle took place in the context of Ramses’ Syrian campaign in 1274 BC. As with the previous year’s campaign, the pharaoh sought to expand into Canaan at the expense of the Hittites. The Egyptian King led four divisions of troops into Canaan, and then northward toward Syria that year. They were named after the Egyptian gods Amun, Ra, Seth, and Ptah. It consisted of as many as 40,000 men, riding 2,000 chariots. These soldiers were reinforced by thousands of Canaanite mercenaries, who joined the pharaoh’s invasion. Not all of those men were deployed at Kadesh, however. Ramses probably used 30,000 men or less on the battlefield. The Egyptians clashed with Muwatalli’s army, which numbered between 25,000 and 45,000 troops. Several thousand Hittite chariots were brought southward into Syria. The armies of the two sides were quite evenly matched. Kadesh is considered history’s largest chariot battle. Ramses was caught off guard at Kadesh. He received faulty intelligence about the proximity of the Hittite invaders. The Egyptian Ra division was scattered by a chariot assault of the Hittites. At this point, the mighty pharaoh summoned his Amun division, and led a counterattack against the Hittites. This broke up the enemy’s chariot assault. Muwatalli was forced to withdraw toward the Orontes River. The Ptah division arrived at Kadesh. The Hittite King ordered a renewed counterattack, but was unable to break the Egyptian advance. Many Hittites had to fling their weapons and armor aside to swim to safety. It is not clear how decisive Egypt’s triumph at Kadesh was. It was possibly a stalemate, although it was presented as a mighty triumph by Egyptian propaganda. Ramses celebrated his victory through numerous steles, inscriptions, poems, and statues. The Poem of Pentaur was read in all of Egypt’s temples. The Battle of Kadesh did not conclude the conflict. The region continued to be contested by Egypt and the Hittites for centuries. Despite this, Kadesh signaled the end of the most feverish and intense conflict between the two superpowers. Smaller skirmishes continued for many years afterward. In 1269 BC, Ramses embarked on a new campaign into Syria, where he conquered the city of Dapur. Even with the personal presence of the pharaoh, Egypt was unable to maintain any lasting control over the region. Finally, the two sides agreed to the world’s first peace treaty. It was signed by Ramses and his Hittite counterpart, Hattusili III, who had acceded the throne sometime in the 1260s. Known as the Eternal Treaty, or the Silver Treaty, the agreement brokered a lasting peace. Both sides were tired of the exorbitant costs of conflict. Syria was left as a Hittite sphere of influence, while Egypt maintained its control over Canaan and the southern Levant. The gods were invoked as overseers of the Eternal Peace. The Eternal Treaty is considered a landmark moment in the history of international relations. Its text has survived from multiple copies in various languages over three millennia later. Two copies of the treaty, written in Egyptian hieroglyphics, were discovered in Luxor, in central Egypt, in the first half of the 19th century. In the early years of the 20th century, German archeologist Hugo Winckler uncovered a copy of the treaty’s text in the Akkadian language, which had been the lingua franca of the Hittite Empire and other states of the Bronze Age Levant. Copies had been deposited in royal archives and temples in cities 2,000 kilometers away from each other. Both Ramses and Hattusili believed that peace and trade in the Levant would be more beneficial than continued hostilities. Both great powers were wary of the Assyrians, who rose to power in Mesopotamia. The Eternal Treaty also enabled Ramses to refocus his military attention to the south of Egypt.

Nubia and Libya

Nubia was an ancient kingdom located in modern Sudan. It was dominated by the Kerma culture, which produced states like the Kingdom of Kush. During the New Kingdom of Egypt, Nubia had increasingly come under pharaonic control. Like Canaan and Syria, Nubia had fell out of Egypt’s orbit following the instability of Akhenaten’s reign. The powerful Ramses was now in a position to reverse this situation, and restore Egyptian dominance in those lands. Early in his reign, he campaigned against the Nubians south of the Nile. By the 1260s, the Egyptian pharaoh had extended his control further down the Nile, in what is now northern Sudan. Ramses’ treaty with the Hittites allowed him to campaign further south against the Nubians, as far down as the Dongola River. There, the Egyptians established a southern military colony at Tombos. Pharaonic and royal inscriptions were discovered in tombs there. By the 1240s, Ramses had successfully annexed a significant portion of Nubia. After reasserting Egyptian influence in Nubia, Pharaoh Ramses turned his attention westward to Libya. Despite its proximity to the dynamic civilizations of Egypt and Crete, little is known about ancient Libya. The Egyptians called the land Tjehenu. The name Libya comes from later Greek descriptions of this same region. Throughout the New Kingdom, Egypt maintained significant contact with Libya. This mostly came in the form of Berber raids into the western branches of the Nile. The Egyptians, for their part, tried to colonize northern Libya. Ramses established new forts along the Mediterranean coastline. Trade and vassal states were founded further west of Libya Proper. By the middle of Ramses’ reign, Egypt had reached its greatest territorial expanse since the days of Thutmose II two centuries earlier. He had successfully annexed Nubia, and campaigned westward into the deserts of the Sahara. He reduced Libya to vassalage. His most consequential efforts occurred in the northeast, where he seized Canaan and Syria from Hittite hands. By the Late Bronze Age, the Great Pharaoh Ramses had transformed Egypt into the most powerful state of the known world.

Pharaonic polygamy

Throughout his campaigns in the 1270s, 1260s, and 1250s, King Ramses came into contact with many women. He had as many as a hundred children, about equally sons and daughters. Egypt’s mighty pharaohs were polygamous. Ramses had many wives, and their lives are well-documented. His main consort was a beautiful woman named Nefertari. She descended from the Pharaoh Ay, who had ruled Egypt four decades prior to Ramses. She and Ramses married very young. She immediately became queen consort after Ramses assumed the throne in 1279 BC. They had many kids together. Nefertari was Ramses’ main wife, and he had many temples erected in her honor. Unusual for women in ancient Egypt, Nefertari’s written correspondence survives. She wrote letters to King Hattusili III and his wife Puduhepa in the 1260s and 1250s. The text survives in the form of tablets, unearthed at the Hittite capital of Hattusa. Nefertari died around 1255. Ramses outlived his wife by many decades. Another significant wife was a woman named Isetnofret. She too married Ramses before he became pharaoh. But she was a junior consort during Nefertari’s lifetime. She became a senior wife after the mid-1250s, as attested by numerous inscriptions and records of her in statues and temple walls across Egypt. Other wives came from the pharaoh’s political arrangements. As part of the Eternal Treaty with the Hittites in 1259, Ramses married one of the daughters of King Hattusuli and Queen Paduhepa. Her name was Maathorneferure. The marriage was not solemnized until the mid-1240s, because the girl was too young for the marriage to be formalized at the time. Ramses’ blood daughter, a girl named Bintanath through his marriage to Isetnofret, was one of his consorts. The disgusting practice of incest was common in pharaonic Egypt, resulting in sickly complications. The famous King Tut suffered from physical ailments because of royal incest.

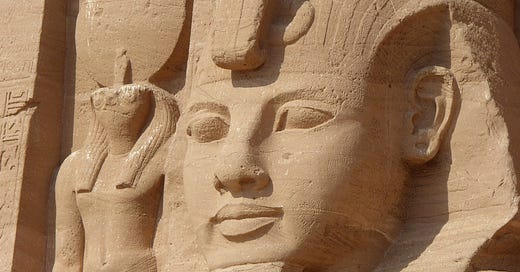

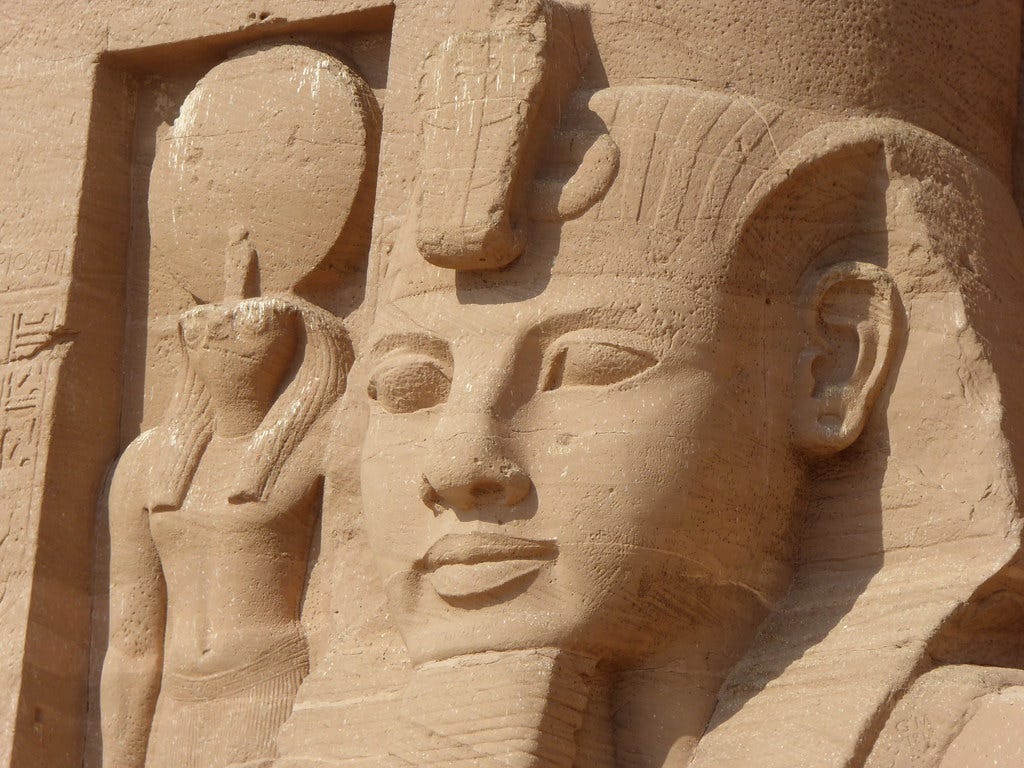

The Great Builder

The second half of Ramses’ reign was characterized by ambitious architectural achievements. Temples, obelisks, and statutes were erected to honor the pharaoh and the gods. This was a departure from Egypt’s traditional emphasis on giant pyramids and royal tombs. The Egyptians worshipped the gods Amun, Ra, Ptah, and Horus. Ramses’ construction projects across Egypt, from the 1260s onwards, sought to connect his royal family with those traditional deities. In the 1240s, after ruling for three decades, Ramses became the object of his own religious cult. The King was celebrated by Sed festivals each year. It was dedicated to the Egyptian wolf god Sed. The festival originated as a ritual murder of the king, but this macabre regicide was replaced by a more benign celebration of Egypt’s pharaoh. Under Ramses, the Sed festival was held at Thebes for the first time in 1249 BC. It was held every three years for the rest of Ramses’ life. He went on to celebrate an unprecedented number of those festivals. At Thebes, Ramses built a necropolis. The Ramesseum took about twenty years to complete. He ordered construction work at Saqqara, not far from the Great Giza Pyramids. There, Ramses enlarged the Temple of Serapis. It was a religious center for the cult of Apis, a bull deity believed to be the physical incarnation of Ptah, who was himself the god of crafts, merchants, and the deceased. Recent archeological discoveries at Saqqara unearthed the Tomb of Ptah-M-Wia, a grand vizier and treasurer in Ramses’ government. The pharaoh’s monumental architecture had a clear political purpose. It was designed to reinforce Egyptian culture in the conquered regions. The crowning jewel of Ramses’ architecture was the temple complex at Abu Simbel. There, he had ordered the construction of two temples back in the mid-1260s. Those took twenty years complete. One of the temples was dedicated to Ramses himself. The smaller temple was built in honor of Ramses’ consort, Queen Nefertari. Upon its completion in 1244 BC, the Great Temple bore the inscription, “The Temple of Ramses, beloved of Amun.” The Temple was designed in a way where it would be flooded with sunlight each year on February 22 and October 22. Those dates might have commemorated the birth and coronation of Pharaoh Ramses. Sculptures and reliefs decorated the interior with scenes of Ramses’ military campaigns, notably the Battle of Kadesh. Four colossal statues adorn the Temple, all of which depict King Ramses. Those statues are among the most famous icons of ancient Egypt.

Death

Despite six decades in power, the last twenty or so years of Ramses’ rule were unremarkable. He suffered from various ailments in old age, including arthritis, atherosclerosis, and dental problems. Ramses probably died in 1213 BC, in the 66th year of his reign, about age 90. This was an extraordinary long age to live. He was interred in the Valley of the Kings. Due to tomb raiding, his remains were moved away from Thebes. His mummified body continues to be studied by modern scholars. Ramses was succeeded by his son Merneptah. This was unusual, because the boy was Ramses’ thirteenth son. But because Ramses lived so long, many of his older sons had already died by that point. Merneptah was already aged in his 60s, and only ruled as Egypt’s pharaoh for ten years. The most notable event of Ramses’ son’s reign was an Egyptian victory against the Libyan tribes at the Battle of Perire in 1208 BC. Ramses’ dynasty died out in 1189 BC. It lasted for little more than a hundred years, most of which were in Ramses’ own lifetime. But in recognition of Ramses’ distinguished reign, monarchs of Egypt’s 20th Dynasty adopted the regal name of Ramses. In total, eleven pharaohs took the name Ramses. The last of them died around 1077 BC.

The Exodus

There is speculation that the mighty Ramses was the antagonist of the Exodus Story in the Bible. The Exodus narrative is one of the oldest sections of the entire Old Testament, and is central to both Judaism and Christianity. In this famous biblical story, the Jews are depicted as slaves living in the Land of Goshen. In the Book of Genesis, Joseph, the son of the Hebrew prophet Jacob, is sold into slavery in Egypt by his brothers. Over the next several generations, a large community of Jewish slaves emerged under the yoke of the Egyptian pharaohs. That is where the Book of Exodus begins. In Exodus, the prophet Moses is placed in a reed basket and sailed down the Nile River by his mother Jochebed, after the pharaoh ordered the murder of Jewish children as a means of population control. Moses is then found and adopted into the pharaoh’s household, where he gains the affections of the Egyptian King. But Moses clashes with the pharaoh’s biological son. This leads to the realization that Moses was adopted. He emerges as the leader of the Israelites, who parts the Red Sea as the pharaoh’s forces attempt to chase him. But there is no strong evidence to really connect Ramses II to the Exodus narrative. The Book of Exodus makes no efforts to identify any historical figures in Pharaonic Egypt at the time. The historicity of the Old Testament is open to speculation. A wide range of pharaohs has been proposed as the biblical villain. In cinema, Ramses is often depicted as the default candidate for the Exodus pharaoh. He appears in the famous movie Ten Commandments from 1956, where he is depicted by the actor Yul Brynner. There are many reasons for this choice. Ramses was the most prominent of pharaohs during the time period. He had an unusually lengthy reign. He also engaged in military conquests of the Levant, which would fit in with the narrative of oppressed Israelites. Besides those basic details, however, there is no conclusive evidence to connect Ramses to the biblical story.

Bronze Age Collapse

After Ramses’ death, the New Kingdom went into a period of decline. Starting around 1200 BC, the Eastern Mediterranean and Levant were struck by a series of foreign invasions, known by the anonymous label of Sea Peoples. There is no modern consensus on who those people were. They possibly came from Italy, southern France, or the northwestern Balkans. The Dorians came from northern Greece around this time. The presence of these new peoples was an immediate threat to the Late Bronze Age world, and began to destabilize Egypt and other nearby societies. This phenomenon is collectively known as the Bronze Age Collapse. Many of the region’s most powerful states either declined or outright disappeared. The Hittite Empire splintered into smaller successor states over the 12th century BC. Mycenae and the Minoans were almost entirely destroyed. Over two centuries of chaos, entire cities were abandoned. Famines struck many regions. The New Kingdom of Egypt managed to survive, although it suffered from civil wars and territorial decline. A new set of regional powers emerged, dominating what had been Pharaonic Egypt. This included Nubia, Egypt’s southern enemy.

Tomb

His tomb was discovered in the late 19th century. The Rosetta Stone had been recently deciphered, ushering in a new golden age of Egyptology. The tomb was discovered at Deir el-Bahari in 1881, near Thebes. Like many royal tombs, the Tomb of Ramses was found looted. Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb about forty years later. Ramses’ tomb is significant for the inscriptions found on the sarphogaus, which lists Ramses’ various names and titles, and provides an inventory of his burial goods. The inscriptions indicate that Ramses was not immediately interred at Deir el-Bahari, and was first laid to rest in the tomb of his father Seti I. It remained there for eighty years, until his body was relocated. The death mask and sarcophagus might have been repurposed from one of his successors, Horemheb, the last ruler of the Eighteen Dynasty. Renovations were carried out on Ramses’ tomb for many years. Royal tombs were something like shrines.

Shelley poem

The pharaoh was the subject of Percy Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias.” The English Romantic invoked Ramses as a symbol of how all powerful rulers must eventually decline or die. It was Shelley’s reflection on the decline of Napoleon’s Empire, who had fallen from power a few years before. News circulated at the time that the British Museum had acquired one of the colossal heads of Ramses from the ancient Egyptian necropolis.

Nasser’s Egypt

Abu Simbel was the site of one of the world’s most extraordinary relocation projects in history. In the 1950s, the new government of General Abdel Nasser, who had seized power in Egypt following the Revolution of 1952, attempted to build a new dam at Aswan in order to control the annual flooding of the Nile. The floods, and the creation of what would have been named Lake Nasser, threatened to submerge Abu Simbel. To avoid this, Nasser’s Egypt asked UNESCO to move the temple in 1959. This petition was granted. Over the next several years, Swedish engineers relocated the ancient Egyptian site on behalf of Nasser’s government. It was an incredibly complex task, and the site had been cut up and reconstituted piece by piece.

Legacy

Ramses continues to be widely regarded as one of Egypt’s greatest pharaohs. His life and legacy remains a staple of Egyptology studies. The Great Pharaoh extended Egypt’s borders to its greatest expanse in two centuries. He conquered much of the Levant, Syria, and part of Mesopotamia. He defeated the mighty Hittite Empire, establishing Egyptian hegemony over the rich coastal cities of Canaan and Syria, such as Tyre and Sidon. The peak of his success was the Battle of Kadesh and its ensuing peace treaty. In the popular imagination, Ramses embodies both the splendor and ephemerality of worldly political power. His memory continues to color International politics to this day, especially in his homeland of Egypt. The mighty Egyptian leader oversaw one of the ancient world’s most formidable empires. He was also a masterful propagandist, whose larger-than-life architecture continues to shape and define our modern understanding of ancient Egypt.

Learn More