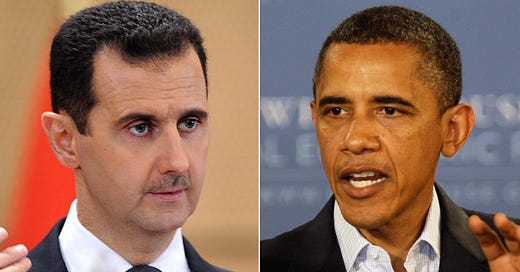

It was 2011. The Arab Spring was in full swing. Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya erupted with democratic movements. In Cairo, Mubarak stepped down from power. Bashar al-Assad, the dictator of Syria, appeared to be next in line.

Revolution of Dignity

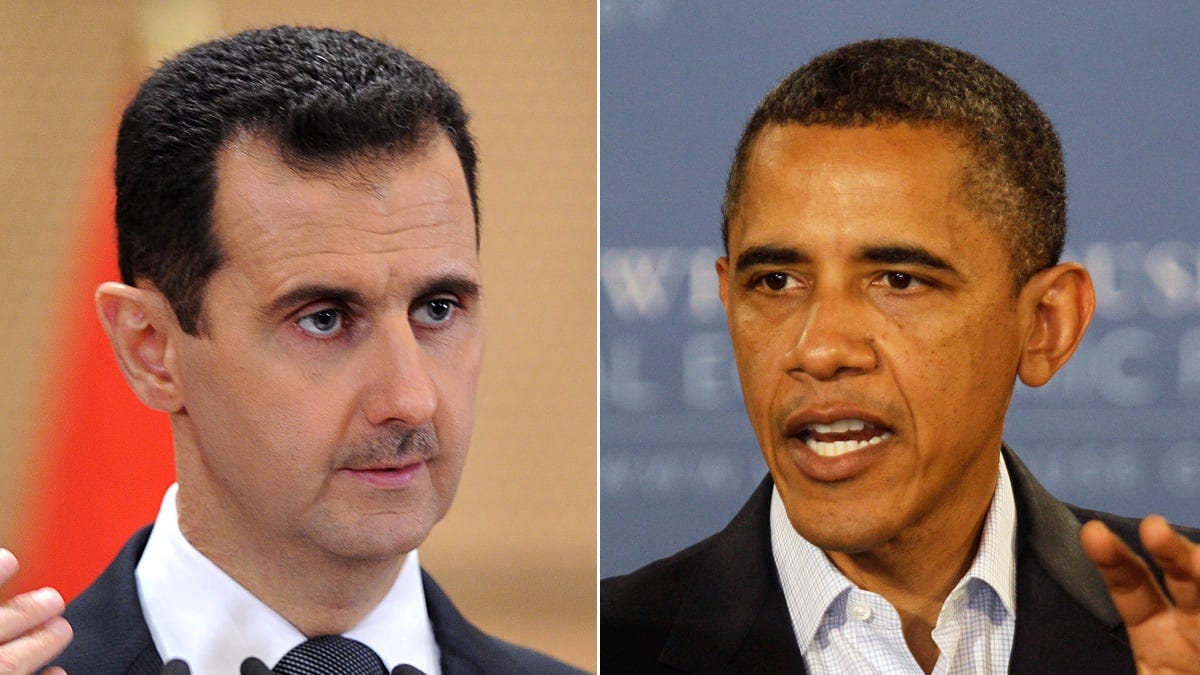

Syrian protestors congregated at the Haria market in Damascus. It was a secular movement, demanding democracy and national unity. Within a matter of weeks, tens of thousands more joined the protests. They enjoyed the enthusiastic support of the US. Americans sent an ambassador to Syria, in the hopes of ensuring a peaceful transition into democracy. But Assad unleashed tanks on the people. Back at the White House, Obama was outraged. “The Syrian regime has chosen the path of murder and mass arrest of its citizens,” the president chided. “The Syrian people have shown their courage in demanding a transition to democracy.” Obama laid out an ultimatum. “President Assad now has a choice. He can lead that transition or get out of the way.” At this early stage, the Obama administration, although supportive of the Syrian protestors, did not feel the need for America to intervene. The White House was confident that Assad’s regime would collapse in a matter of weeks. This optimistic belief was shared by Israel, the Muslim Brotherhood, and Turkey alike. But Assad refused to relinquish power. He brutally crushed the protests. Now, the Syrians had to resort to armed resistance. Assad countered with the brutal force of helicopter gunships, long-range artillery, and eventually bombers. A brutal civil war was at play.

Syria’s civil war

The Obama White House listened closely to the assessments of the CIA. CIA Director Dave Petraeus took note that Assad’s Shiite allies, Iran and Hezbollah, were rallying to the regime’s side. The Iranians airlifted aid to Damascus, while Hezbollah instigated more turmoil in neighboring Lebanon. Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard provided crucial contributions to shore up Assad’s governmental forces. Senator McCain called for airstrikes against Syria, hoping to create safe havens for the anti-Assad rebels. But the Obama administration was wary of this choice. After airstrikes against Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, the democratic movement failed to organize a stable government. An estimated 70,000 Americans would be needed to wipe out Assad’s formidable Russian-supplied air force defenses. The president also had to consider the legality of invading a sovereign nation. Beyond the White House itself, another Middle Eastern war was the last thing anyone wanted in America. Plus, Obama had other priorities, such as healthcare reform. The situation only grew worse, as al-Qaeda affiliates from Iraq poured into neighboring Syria. These new fighters were well-financed and more radical than ever. They would eventually become ISIS. The terrorists were financed by their Sunni co-religionists in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton wanted to ensure that these extremists would not overtake the more moderate elements of the Syrian opposition. But the moderates were hopelessly disorganized and outmatched.

Covert conflict

The Obama administration debated on how to distinguish between the moderate and extremist elements of the Syrian opposition. To manage the crisis, Petraeus recommended a covert action to arm the Syrian rebels from secret bases in Jordan. It gave the White House plausible deniability for any legal challenges to overthrow a sovereign government, or if the weapons turned up in the wrong hands. Petraeus’ proposal was endorsed by Secretary Clinton and Defense Secretary Leon Panetta. Obama’s administration was deeply divided on what to do. Recent history seemed to provide contradictory lessons. The Balkans showed how US intervention could prevent a humanitarian catastrophe and depose dictators. The Iraq War, on the other hand, demonstrated the limits on American military power. The strongest advocate for arming the rebels was Samantha Power, the head of Obama’s newly formed Atrocities Board, and author of the book A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. Taking lessons from the Balkans and Rwanda, Power was adamant that America needed to intervene in Syria. But some of Obama’s advisers vocally warned against it. By the fall of 2012, Aleppo was still up for grabs, even as the rebels suffered heavy losses. Finally, Obama made up his mind. Against the advice of the State Department, the president announced his decision not to get involved in Syria.

Chemical weapons

In early 2013, Assad appeared publicly for the first time in six months. Addressing his supporters, the Syrian president lambasted the rebels as unhinged lunatics. “They call it a revolution,” Assad scoffed, “but it has nothing whatsoever to do with revolutions. A revolution needs thinkers. A revolution is built on thought. Where are their thinkers?” “They are a bunch of criminals,” he declared of the rebels. As he spoke those words, Assad’s air force was assaulting schools, hospitals, and breadlines. After two years of war, more than 60,000 Syrians had already been killed. Hundreds of thousands were forced to flee their homes. Refugee camps appeared in Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey. Russia and Iran continued to back Assad, and most Western nations did want to get involved. Without anyone to stop him, Assad took an audacious new step. The Ba’athist dictator prepared to deploy chemical weapons against his own people. It was a calculated move to completely diffuse all dissent. When asked by the press, President Obama explained that any use of chemical weapons by Assad’s regime would change his mind on intervention. He had effectively laid down a red line against Assad. The Syrian rebels were highly encouraged by Obama’s off-the-cuff remarks. Despite Obama’s threat, Assad remained defiant. The chemical weapons began as isolated incidents. Then it escalated into a pattern of larger use. Phosphorus bombs rained down on the people. The Assad regime used sarin, a vicious nerve agent that causes asphyxiation by lung paralysis. American intelligence estimated that up to 1,400 people were killed, including women and children.

Red Line

Obama now felt under pressure to enforce the red line. “The indiscriminate slaughter of civilians, the killing of women and children and innocent bystanders by chemical weapons, is a moral obscenity,” Secretary of State John Kerry announced boldly. “President Obama believes there must be accountability for those who would use the world’s most heinous weapons against the world’s most vulnerable people.” The president ordered the military to get ready. But Obama began to have doubts. The British Parliament refused to back the US-led intervention. Obama reluctantly chose to ask Congress for authorization of a strike on Syria. Before the Obama administration could intervene in Syria, the Russians offered a peace proposal for Assad to relinquish his chemical arsenal. Obama, who hated the idea of intervention in the first place, eagerly accepted a negotiated settlement.

ISIS

Back in Syria, extremists exploited America’s decision not to attack. They convinced the Syrian rebels that the West and its regional allies had completely abandoned them to Assad’s whims. By January of 2014, most of the Syrian moderates simply defected to the extremist cause. ISIS emerged as the strongest of these fringe factions. They wrestled control of the provincial capital of Raqqa, in northeastern Syria. The city of a million people became the capital of a new caliphate. Six months later, ISIS crossed into Iraq, seizing the country’s second-largest city of Mosul. They were warmly welcomed by the Sunni residents. The fall of Mosul came as an utter shock to US officials. Facing almost no resistance, the heavily-armed ISIS fighters moved deeper into Iraq, capturing town after town. They chased down thousands of Christians, Yazidis, Shabaks, Turkmen, and other minorities from their homes. In Tikrit, the birthplace of Saddam, they rounded up and massacred 1,700 Shia soldiers. The terrorists posted the video online. In August, ISIS captured an American journalist named James Wright Foley. They released a video titled, “A Message to America,” where they beheaded the man. Now, the foreign threat became a domestic one. After three years of trying to avoid another Middle Eastern war, President Obama announced his intention to deal with ISIS. He declared the Islamic state to be a threat both to the region and the US. Obama assembled an international coalition. He authorized airstrikes in Syria for the first time. For four months, the US launched airstrikes against ISIS-occupied Iraq. Kurdish volunteers from Iraq and Syria fought against the caliphate. Only after brutal fighting, the Coalition finally managed to kick ISIS out of Kobani, Syria. ISIS responded by blending into the civilian population. This meant that only a ground force could dislodge the Islamic state. By the final years of Obama’s presidency, Syria had exploded into an unsolvable problem. After five years of civil war, over 220,000 Syrians had died. Half of Syria had been forced from their homes. Inspectors suspected that Assad still possessed sarin gas. The Syrian dictator weaponized chlorine as well.

Learn More