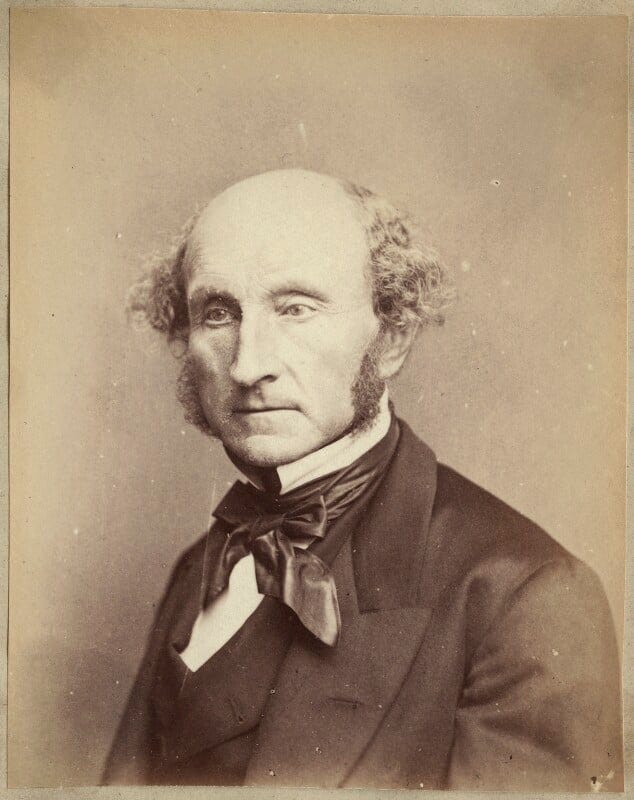

John Stuart Mill: The Classical Liberal

Meet the most influential political thinker of 19th-century England.

John Stuart Mill was the most ground-breaking liberal theorist of the entire 19th century. A prodigy from childhood, Mill made seminal contributions to philosophy, economics, logic, and political science. As a member of British Parliament, he was closely involved in the Empire’s domestic and foreign policy.

Mill was a champion of representative government, women’s rights, secularism, economic freedom, and personal liberty. Many of his ideas are widely accepted today in the West, but there were once extremely radical.

English Radicals

Mill was born in London on May 20, 1806. His father, James Mill, was a Scottish intellectual who followed the utilitarian philosophy of English reformer Jeremy Bentham. The elder Mill wanted his son to become a genius. Bentham, as well as his father James, were foundational influences on John Stuart Mill.

Bentham had been an early advocate for free speech, animal rights, the abolition of slavery, women’s equality, and—perhaps most offensive to Victorian sensibilities—the decriminalization of homosexuality. Bentham’s groundbreaking ideas were regarded as pariahs to polite English society. Bentham and his followers were called Radicals, and were distinct from Tories and Whigs alike.

Inspired by Enlightenment intellectuals, such as Voltaire, Bentham and his followers emphasized the role of reason above tradition and custom. His empiricist psychology, known as associationism, sought to explain consciousness in terms of associations between various perceptual elements. Bentham saw humans as fundamentally motivated by pleasure and pain. His mummified corpse is currently held by the University College in London, whose commitment to secular education he helped inspire.

James Mill

James Mill’s intellectualism earned him the patronage of Sir John and Lady Jane Stewart. He later tutored their daughter. Mill fell in love with this young woman, but the romance could not be had. She was, after all, the daughter of his aristocratic patrons. Right away, this formative experience was the beginning of Mill’s lifelong hatred of England’s rigid social hierarchy. He later named his own daughter Wilhelmina after this forbidden love.

For a short time, Mill became a Presbyterian minister. However, his sermons were deemed too intellectual for the common people. He married a woman named Harriet Barrow in 1805. Together, they had nine children. The family struggled financially, until James Mill published his History of India.

A young genius

Under the hard-driving tutelage of his father James, John Stuart Mill was engulfed in the glories of Western civilization from an early age. He intimately understood Roman history and English government. By age 14, he had read most of the classics of Antiquity. By 16, Mill had skills in economics, politics, history, higher mathematics, logic, and all branches of philosophy.

Mill began working for the British East India Company. This gave him a comfortable income, allowing Mill to pursue his intellectual interests. Mill continued in this role until the Company’s dissolution following the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857.

Mill’s studiousness had severe consequences on his mental health. The English philosopher suffered a nervous breakdown. This forced him to think and live in a healthier way. Going into his twenties, Mill continued to read widely and befriend the leading intellectuals of the age.

In 1836, Mill’s father died of pulmonary attacks, a complication of tuberculosis. John, now 30, was overcome with grief. He fell into a depression, but eventually recovered.

Utilitarianism

In 1838, Mill published an essay on Bentham. Although he was raised in this ethical philosophy, Mill came to feel that Bentham’s utilitarianism was too narrow and cold. Above all else, Mill admired the willingness of his intellectual mentor to question authority.

Mill infused Bentham’s cold philosophy with the warm emotivism of the English Romantics. In them, Mill found an antidote to the austerity of his childhood and education. The arts and philosophies of the Romantics gave Mill a greater aesthetic appreciation for the beauty of the natural world and his own human emotions.

Feminism

Mill was a staunch advocate for women’s rights at a time before they had the right to vote. In The Subjection of Women, Mill objected to the legal subordination of women to men, or vice versa. He saw this as intrinsically immoral, and a primary hindrance to human progress. He called for a new system of perfect equality, in which neither men nor women enjoyed special privileges over the other. Mill criticized the idea that women were “naturally” inferior. He blamed much of women’s lack of progress on their subordination to men through the centuries. Because of his feminism, Mill was viciously mocked by his fellow, mostly male intellectuals.

Much of Mill’s feminism was inspired by his own burning dedication to his lovely wife. Mill met his future wife, Harriet Taylor, in 1830. The beautiful young woman was bright and articulate, but married. Smitten with her from the beginning, Mill eventually became the mutual object of these affections. She liked him too. To avoid scandal, though, they avoided excessive displays of affection in the early years of the marriage.

Harriet lived in a separate residence with her daughter beginning in 1833. This quiet arrangement continued until Mr. Taylor’s death in 1849. Two years later, in 1851, John married the love of his life. During this drawn-out, sexless phase of the marriage, Mill composed some of his best-known works.

Mill’s marriage was a generally happy one, and he was devastated by her death in 1858, just seven years into the marriage. She was the saving grace of his life. Her daughter, Helen, became an actress and kept contact with Mill until his death at the age of 66. Despite being a widower for 20 years, Mill did not remarry or have romances with other women.

Economics

His Principles of Political Economy revolutionized the social sciences, and he is considered the last of the great classical economists. He offered major insights into comparative advantage, international trade, opportunity cost, and theories of innovation.

Unlike his predecessors, Mill paid attention not only to the creation of wealth, but also its distribution. Moreover, he was one of the first to admit the inherent difficulty in predicting economic phenomena.

He sought to position himself between the two extremes of Thomas Malthus and Adam Smith. He stayed away from the gloomy predictions of Malthus that population growth would always outpace production. But Mill also expressed skepticism about the ability of Adam Smith’s proverbial “invisible hand” to efficiently allocate resources. Instead, Mill’s economic analysis proposed a range of alternative possibilities, based on the pace of technology and other hard-to-predict variables.

Mill disagreed with the Social Darwinism of Herbert Spencer, although the two men were personally friends. He helped finance some of Spencer’s books. Mill was also friends with David Ricardo, another famed economist.

While Mill was not a free-market absolutist, he did recognize the pitfalls of collectivist economies and excessive taxation. He supported capitalism and entrepreneurship, which he saw as providing the greatest amount of personal autonomy—the cornerstone of his ethics.

It has been speculated that his wife softened Mill’s stance toward socialism. He later added a chapter about labor to his Principles of Political Economy. However, Mill maintained that competition was necessary for progress, and was generally skeptical of government inference with private business.

Logic

In his System of Logic, Mill argued in favor of individual freedom and public education. He generally rejected syllogism and deduction in favor of the inductive methods of Bacon and Hume. He investigated the idea of causality.

Politics

Mill’s most enduring contributions to Western thought lie in his unique approach to political theory. He was deeply interested in the relationship between the individual and society. In his landmark work On Liberty, Mill argued strongly in favor of personal autonomy and freedom, with very few qualifications. However, he did support compulsory public education, as well as tests for voting rights. The individualist thinker felt that true geniuses could flourish in an atmosphere and culture of freedom.

Death and legacy

Mill spent his final years at Avignon, close to his wife’s grave. He died in 1873, and was buried beside her. Throughout the Victorian era, Mill’s grave was lavished with attention. Despite his Radicalism, the forward-thinking Mill was appreciated by the Victorians as the last great Romantic of the English tradition.

Today, John Stuart Mill is regarded as one of the greatest thinkers to come out of his entire era. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy lauded him as “the most influential English-speaking philosopher of the 19th century.”

Over two centuries later, Mill’s revolutionary ideas continue to inspire liberty movements around the world. In death as in life, he remains a tireless advocate for individual freedom against despotic governments and tyrannical taboos.

Learn More