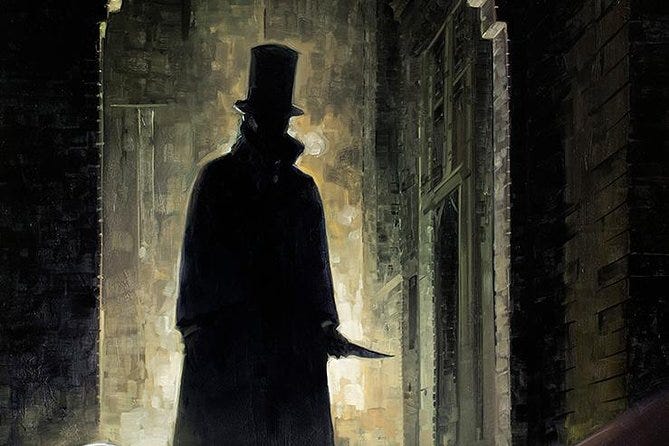

Jack The Ripper: The First Serial Killer

How a series of Victorian murders gave birth to modern police forensics.

Victorian England underwent seismic shifts over the second half of the 19th century. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, many people began moving out of rural homes into crowded cities. But urbanization was accompanied by the rise of urban crime. No one embodies the newfound dangers of modern life in cities than the frightening figure known to history as Jack the Ripper.

London

The year was 1888. London was the world’s largest city. It was the beating heart of the mighty British Empire, which boasted a population of about five million subjects. At the time, most people living in London worked within a walking distance of their homes. Streets were narrow and very heavily crowded, especially in the East End. From 1888 to 1891, the districts of Whitechapel and Spitalfields would be struck by an unthinkable atrocity. Eleven innocent women were brutally murdered by a serial killer, whose identity has never been uncovered. He is simply called Jack the Ripper. However, it is possible that not all of these killings were the work of a single person. The West End was full of horse-drawn carriages, fancy clothing, and the fancy balls of polite society. But that was in the richer part of town. England was sharply divided along class lines. Many areas lacked this kind of opulence and grandeur that we traditionally associate with the Victorian period. The East End was overcrowded, destitute, and full of every sort of criminal activity.

Whitechapel

Whitechapel was an especially unpleasant borough of London’s East End. The tiny area had a population of 75,000 people, spanning an area of 1.5 square kilometers. This means that over 200 people occupied every acre of land at any given moment. It was a working-class area. Working days typically consisted of 12 to 18 hours of hard labor. Weekends did not exist. Employees received barely enough money to survive. Prospects were bleak. Many workers spent their few leisurely hours at the pub, drowning their sorrows in the bottle. Cries of murder and violence were a nightly occurrence. The working women of Whitechapel had few economic opportunities. They could not afford to eat or own a home. Many of them were forced to resort to prostitution. As many as 1,200 prostitutes roamed the streets of Whitechapel alone. People were so poor that they literally lived in the streets. Many of the impoverished had to reside in common lodging houses to receive their food and shelter each night. Those who could not afford beds had to sleep in workhouses or the streets. As an institution, the police was still in its infancy. London’s Metropolitan Police had recently formed, and they were not taken very seriously. Whitechapel was an especially difficult borough to police, and patrols often missed areas.

First blood

Jack’s grisly saga begins in Whitechapel in April of 1888. The first victim was a woman named Emma Elizabeth Smith. Very little is even known about Smith. We don’t know where she came from. Case files from the time indicate that even her close associates didn’t know who she was. She was probably about 45 years old, and claimed to be a widow. Her speech reflected a higher level of education than many of her peers. In the early morning hours of April 3, 1888, Smith was viciously assaulted at the junction of Osborne Street and Brick Lane. Her injuries were severe, but she survived. She made her way to a nearby commons lodge. There, she said she had been attacked by two or three men, including one teenager. She became unresponsive, and died of her injuries at 9am on April 4. This was a full day after her attack. Based on the details of the attack, many modern scholars do not think Smith’s death was the work of Jack the Ripper at all. The criminals were never identified, but the crime is generally grouped together with the Ripper cases, which all took place at Whitechapel.

Another victim

A few months passed without any major disturbances. But on Tuesday, August 7, 1888, another victim was found. Her name was Martha Tabram, another working-class woman. She had been working as a prostitute in the area. An autopsy found she had been killed around 2:30 am. She had been stabbed around her neck, torso, and genitals by a short blade 39 times. Her attacker was right-handed. Tabram’s case was invested by Detective Edmund John James Reed of the London Metro Police. An expedition of soldiers were organized at the Tower of London, but no suspect could be found. It is again unclear whether Tabram’s murder can be connected to the canonical five Ripper cases. Her wounds were stabs, not slashes. However, her murder lacked a suspect and a motive, and they took place near the other five Ripper victims.

Polly

Jack the Ripper struck for the first time on August 31, 1888. The first canonical victim was 43-year-old Mary Ann Polly Nichols. She had a lengthy police record for minor offenses, such as drunkenness, disorder, and prostitution. A former housekeeper, she had recently been fired for stealing from her employer. The woman relocated to a commons lodging just days before her death. She was last seen at 2:30 am by a witness named Emily Holland. Her dead body was discovered by a man named Charles Allen Cross, who was on his way to work. He informed a local constable, who investigated the macabre affair. The post-mortem results were truly horrifying. Both sides of her face were bruised by what was probably a fist. She had missing teeth and a cut tongue. Her throat had been brutally cut twice. One wound was eight inches, while the other was four. Both wounds were cut deep, reaching near her spine. She had nearly been decapitated. The neck was apparently struck first, reducing the blood and causing a quick death. She had been stabbed twice in her genitals, and her stomach had been ravaged by several incisions. Her bowels stuck out from the wounds. The knife of the killer was about six to eight inches in length—a common size knife for cork cutters, shoemakers, or even butchers. The cuts were inflicted in an aggressive downward thrust. No organs were missing. Some wounds were inflicted after her death, suggesting that the culprit had some anatomical knowledge. It all happened in a span of about five minutes. Initial investigations were unable to find anything. The press linked Polly’s murder to the previous two killings, suggesting it might have been the work of a gang. Gangs were common in London’s East End. The Star newspaper speculated it was the work of a single murderer. Although the term hadn’t been coined it, people were now talking about what might be a serial killer. The area was surrounded by butchers, so it would have been easy for even a single blood-stained culprit to evade detection.

Annie

On September 8, 1888, around 6 am, the remains of 47-year-old Annie Chapman were discovered. Having left her lodgings four hours before, she had been raising money through prostitution to pay her rent. Born on September 25, 1840, she was the first of five kids. Her father George Smith was a soldier. She was a heavy drinker from an early age, despite the misgivings of her family. She married John James Chapman in 1869. Troubles with their kids made them turn to drinking. By 1884, their marriage had imploded. She relocated to Whitechapel, surviving on the meager allowances of her former husband. Annie became depressed, losing her will to live. She asked to use the bathroom at a place. The owner heard a woman’s voice and then a thud. Because of the rampant crime, he did not bother to investigate. Her body was discovered by authorities shortly after. Her throat was cut from ear to ear. She had been disemboweled. Her intestines had been pulled out from her stomach and thrown over her shoulders. A post-mortem examination found that part of her uterus was missing, and had been removed with a single slash. The size of the killer’s knife was the same as the Polly murder. This led many people to conclude that the Ripper had struck again. A pathologist named Dr. George Baxter Philipps suggested that the killer had anatomically knowledge in order to remove the uterus with a single cut. But his judgement was disputed by many other medical experts. A witness named Elizabeth Long said she saw Annie talking to a man just 30 minutes before the murder. He was described as over 40 years of age. He was taller than Chapman, who stood at only five feet. He had dark skin. Although he looked poor, he dressed fairly well. He wore a brown deer-stalker hat and a dark overcoat. Panic broke out all over London. The press called the mysterious murderer “Leather Apron.” The name was used for another killer named John Pizer, who was known to terrorize the local working women. After some research, investigators quickly concluded that he was not the murderer. All sorts of theories spread. The Metro Police offered a reward of 100 pounds for any information leading to his capture. In today’s money, that would be about 10,500 pounds. A hairdresser named Charles Ludwig was briefly suspected. But when the Ripper struck twelve days later, it became obvious that the real killer was still at large.

Double event

Things only got worse when, on September 30, 1888, the Ripper killed two more victims. It was Sunday. The body of a 44-year-old Swedish woman named Elizabeth Stride was discovered by a reward at the nearby International Working Men’s Educational Club. Her throat had been cut, and she was laying in a pool of her own blood. Unlike Polly and Annie, her corpse had not been mutilated. The murder had taken place just moments before her body’s discovery. This suggested that the killer was disturbed before he could commit his egregious acts. It also meant that the killer could not be far from the location. 25 minutes before the discovery, Stride had been spotted with a man wearing a hat by Constable William Smith. The suspect had been holding a 1.5 foot long package. Shortly after, a doc worker had spotted Stride speaking with a man of average build, wearing a long black coat. She was heard saying, “No, not tonight.” The body was still warm, suggesting that the Ripper had almost been caught. But the Ripper wasn’t done with his unspeakable crimes. The killer, apparently frustrated, sought out another unfortunate victim. Within an hour of where Stride had been found, the Ripper struck again at 1:45 am. Her name was Catherine Eddowes, a 46-year-old woman who lived in a lodging house on Dean Street. She had been killed a mere 10 minute before her discovery. Her throat was slashed from left to right. The knife was probably at least six inches long. The face and abdomen were gruesomely disfigured. The intestines had been pulled out and thrown over the right shoulder. Her left kidney had been removed, along with most of her uterus. Catherine’s case was looked at by pathologist Dr. Frederick Gordon Brown. Brown concluded that the serial killer had considerable knowledge about the position of the organs. From the placement of the wounds, he could tell the Ripper had knelt to the right of Catherine’s body. Brown argued that these ghastly murders were the doing of a single man. Around 3 am, a blood-stained part of Catherine’s apron had been found in a doorway en route between the two murders. Chalk writing on the wall read, “The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.” The graffiti was quickly removed to prevent any anti-Semitic riots. Because of how common graffiti was, it was not clear if there was really any connection with the Ripper murders. Nevertheless, the ominous wording found its way into the press, generating much discussion. A Hungarian immigrant named Israel Schwartz gave an account of the night. Following Stride’s murder, he had entered Berner Street around 12:45am. Shortly ahead of him, he saw a man walk up to a woman and throw her to the ground without provocation. He crossed the street to avoid getting involved. An onlooker from a nearby pub accused Schwartz of perpetrating the murder, yelling anti-Jewish slurs at him. Israel fled the scene, fearing a case of mistaken identity. Stride died soon after. Schwartz was allowed to see the dead body, and he identified her as the woman he had seen earlier. Schwartz described the man as 30 years old, five-foot-five, with broad shoulders, dark hair, and a brown mustache. This description matched that of Joseph Lawende, a local cigarette salesman. Joseph described the Ripper as dressed like a sailor, of average build, with a fair skin tone and a brown mustache. The congruence between the two descriptions seemed to suggest that the Ripper had changed clothes between the murders, and that the murderer was a local resident.

Letters from Jack

London’s working-class people grew increasingly impatient with the Metropolitan Police. The police force was still new at the time, and was already deeply distrusted by the people. The Mayor of London offered a reward of 500 pounds, which is worth over 50,000 pounds today, for any information on the murderous maniac. On September 27, 1888, the Central News Agency received the so-called “Dear Boss” letter from the Ripper. Written in red ink, the letter taunted the police, and promised to email a woman’s ear to them. The letter is now considered to be a hoax. However, after Catherine’s murder three days later, part of her ear was missing. But the most important thing is that the letter contained the first documented use of the term “Jack the Ripper.” Very quickly, the unnamed killer came to be known by this title. On October 1, 1888, the Central News Agency of London received another item. It is known as the “Saucy Jackie” postcard. Both of these items were hoaxes, and were identified as such by London’s police at the time. In 1931, journalist Fred Best confessed to forging the letter and postcard as a way of maintaining public interest in the case and driving up sales of his publication. Despite their fraudulence, the letter and postcard inspired many other people to write prank letters to the press posing as Jack the Ripper. After Annie Chapman’s murder, George Lusk founded a Vigilance Committee to hunt down the Ripper. He received a letter claiming to be Jack. It came with a package that contained half a human kidney. At first, Lusk thought it was a fake, but he decided to hand it over to the Metro Police. The kidney was confirmed to be of human origin. The person who had this kidney suffered from Bright’s Disease, known today as nephritis. It belonged to a sickly alcoholic woman who had died within the previous three weeks, matching the Catherine Eddowes case. Known as the “From Hell” letter, it is one of the only articles that might have actually been real. The letter differs from the other letters. It is addressed to a specific individual in the community, rather than the police. This suggests that the Ripper had some sort of personal animosity against Lusk or the woman. It was not signed off as Jack the Ripper. The level of literacy of whoever wrote it is lower than the other alleged letters. The handwriting is very erratic-looking. Even as the Ripper went unseen throughout October of 1888, the police worked furiously to apprehend him. They interviewed over 2,000 people, including 300 suspects and 80 arrests.

Mary Jane

On November 9, 1888, the silence was broken. Another victim was found. She was an Irish woman, around the age of 25. Her name was Mary Jane Kelly. She was younger compared to the Ripper’s other victims. She was discovered after the landlord came to collect her six-week late rent. Unlike the other canonical five, she was murdered indoors. Her room was poorly furnished, suggesting she was a woman of little means. She was killed by a rapid slash to the throat. But due to the privacy of the residence, the Ripper had plenty of time to mutilate the corpse. It was estimated that she had been killed between three to nine hours before her discovery. This time, professionals were at the top of their game. Inspector Walter Beck immediately requested help from police pathologist George Bagster Philips. He gave orders preventing anyone from contaminating the crime scene. Photographs of the crime scene reveal some of the most sickening sights imaginable. But the diligence of these investigators pioneered many of the methods still used today by modern police. Investigators determined that the killer had broke into the house around one in the morning. The fireplace burned especially hard, because the Ripper had thrown the woman’s clothes into it. Kelly’s remains were taken to a mortuary, where she could be formally identified and examined. Of all the Ripper’s victims, Kelly’s corpse was mutilated the most. Philips suggested that the carvings took place over a couple of hours. The knife was six inches. He did not think that the Ripper had any scientific or anatomical knowledge at all. Kelly was the last of the Ripper’s five canonical victims.

Autumn of Terror

London broke out in panic. Scotland Yard telegraphed news of the killing, spreading rapidly across the East End. The public grew increasingly restless, aiming their anger at the police for not stopping the killer yet. Mary Jane Kelly is considered the last of the canonical victims, but other murders occurred for the next three years, from 1888 to 1891. Whitechapel was afflicted by another four murders, but it is not clear whether the Ripper was the one who did them. These were Rose Myles, Alice McKenzie, Frances Coles, as well as an unidentified woman’s torso found on Pinchin Street. Due to the similarly brutal nature, the Ripper cases became associated with the Thames Torso Murders a few years before. However, it is generally concluded that the two murderers were different individuals.

What happened?

How on Earth did the Ripper go unpunished for his atrocities? This is because, in the Victorian era, law enforcement lacked the tools they have now. There were no cameras, forensics, or profiling expertise for a murderer of this caliber. Serial killers were not yet a widely understood phenomenon. It didn’t help that the victims were usually strangers, which gave no clues on the Ripper’s origins or motivations. Nor did it help that the British public had a misplaced skepticism and mistrust of the police, which was still a new institution at the time. Investigations were very disorganized. Like the crimes they studied, these were sporadic and unconnected. After Catherine Eddowes was killed in proper London, rather than Whitechapel, two different police forces were working on the Ripper cases. The whole process was sloppy and ineffective. Apart from eye witnesses, no one knew anything about the Ripper. The sensationalism of the media only confused the situation further.

Birth of modern forensics

The Ripper murders were absolutely vile and unspeakably evil. But they are still worth studying, because it yields numerous insights into psychology and criminal studies. Moreover, the Ripper cases occasioned a breakthrough in modern forensics, such as criminal profiling. Horrified by the barbaric murders, Victorian England took immediate steps to clean up the streets. After Mary Jane Kelly’s murder, police patrols nearly doubled in number. This bolstering of police presence may have been ordered by Queen Victoria herself, who was reportedly well-informed about the notorious Ripper atrocities. She personally telegraphed to Prime Minister Gascoyne-Cecil, demanding instant action. Most of the Ripper files were destroyed during the Blitz of World War Two. But enough of them still survive to give us a better picture of how Victorian police operated. At first, the police thought that the murders were done by gangs. But over time, they came to realize that the murderer was a lone assassin, which would explain why so little was known about the murders. Police conducted house-to-house interviews, even asking male suspects outright if they were the Ripper. Investigators took photographs of the victims’ eyes, hoping that the retina would retain the frozen image of the killer. This theory was called optography. It did not take long to realize the falsehood of this forensic method. Police sometimes dressed in plain clothes, which was an early form of sting operation. But they inadvertently gave away their identity as cops because of their police boots. Journalists tried dressing up as women at night, hoping to catch the killer. But this silly method did nothing. Police resorted to offering rewards, but nothing bore any results. Ad hoc testimony offered nothing in the way of concrete knowledge. Evidence was handled haphazardly by many hands, while crime scenes were not even preserved. But because of Jack the Ripper, the London Metropolitan Police transformed from a laughing stock into a serious investigative police force.

Lessons

The sadistic psychopathy of the Ripper demonstrates the tragic reality of human evil in starkly visceral terms. It demonstrates the persistence of barbarism in modern industrial societies, even amid vast improvements in the material standards of living. In some sense, it is a bitter warning against a blind faith in progress and human perfectibility. On the sociological level, such savagery speaks volumes about the rigid class structure of Victorian England. Class is the unspoken factor in the whole ghastly ordeal. Poverty is the root of many evils, including violent murder, involuntary prostitution, alcoholism, and familial instability. By alleviating poverty, we can prevent the conditions which might occasion such shocking atrocities. Jack the Ripper’s macabre deeds are a shocking spotlight into the unspeakable depths of human depravity. But more importantly, these gruesome murders were a landmark in the development of modern policing. Forensics have come a long way since the Ripper’s time. In truly Victorian fashion, the Ripper cases show the moralistic potential of modern technology to punish criminals and create a more just society.

Learn More