Hyundai: The Korean Car

How a South Korean peasant built one of the world's greatest car brands.

Just a few decades ago, Hyundai was seen as a cheap, junky Korean knockoff car. It was little more than a joke, a punchline. But now, Hyundai offers some of the hottest cars on the market, competing successfully against industry giants like Ford, Honda, and General Motors. Today, it is the world’s third largest producer of cars, behind Toyota and Volkswagen.

Hyundai’s unlikely success was the brainchild of Chung Ju-yung. Despite his humble origins, this South Korean entrepreneur rose to become one of the titans of the global automotive market. Here is the thrilling story behind South Korea’s Hyundai brand.

Poor origins

Chung was born in 1915 in a small village from Tongchon, in modern-day North Korea. At the time, Korea suffered under the harsh colonial yoke of Imperial Japan. His impoverished family barely made their subsistence through long, hard hours of farming. Yung had dreams of becoming a schoolteacher. However, being the oldest of seven kids, necessity forced him to drop out of school at the untimely age of 14 to work alongside his father. From dawn to dusk, he arduously toiled to plant and harvest rice by hand. He raised the livestock, and traveled from town to town selling firewood. Even with all of this hard work, the family could barely afford to eat. They were perpetually one harvest away from utter starvation.

Tired and frustrated by this abject condition, the 16-year-old Yung left his village in search of a better life. He walked long miles through the most dangerous parts of the country, until he arrived at the city of Kowon, which is part of North Korea today. There, they found jobs as construction workers.

Even though his wages were nothing to speak of, Yung was deeply happy. He found it much better than the back-breaking exhaustion of farm life. Furthermore, he was entranced by the prospect of earning and keeping his own money. Unfortunately, it only took two months before his father found him and brought him back to the family’s farm. But the taste of a better life would not leave Yung’s lips. Four times, he escaped to the city of Seoul, what is now the capital of South Korea. The last of these would be permanent.

Seoul food

When Yung arrived in Seoul, he took any job he could find. He worked as a laborer, construction worker, and a handy man at a starch syrup factory. The next year, he found better work at the Bokheung Rice Store. There, he was employed as a deliveryman, delivering rice on his bicycle. Unlike his previous jobs, it was stable. His employers were so impressed by his work ethic, that he rose to the rank of store accountant after just six months. Over the next few years, the store’s owner fell ill, and he sold off the business to his young apprentice. At the age of 22, Yung took over as the rice store’s chief executive.

He changed the store’s name to the KYungil Rice Store. Through his low prices, he managed to attract a strong customer base. The business’ profits rose under his leadership, and became one of the best rice shops in town.

When Imperial Japan seized power, they imposed rice rations on Korea. This was done to provide supplies for the Japanese military, which was at war with China. As a result, many Korean business owners were forced out of the rice trade, including Yung. Forced out, Yung now had to return to his farmland.

Garage shop

Yung managed to return to Seoul in 1940. He tried his luck in a new business venture, one that was free from the restrictions of the colonial Japanese regime. One of these industries was car repairing. His destiny was now paved out for him. Taking out a bank loan, he opened up his next business: the A-do Service Garage.

At the time, the demand for auto repair was very high in the city. But there were only a few shops around, and they usually charged exorbitant prices. Yung himself knew nothing about cars, but he hired out a talented mechanic. The Korean entrepreneur managed to outclass his competition by selling his services at extremely cheap prices. Yung also took great pains to provide the best possible customer service. Yung’s car business soon blossomed, and he had to hire out even more mechanics to keep up with work.

Things were thriving, until an inauspicious fire burned down the entire shop. Equipment, as well as the customers’ cars, were razed to the ground. This thrust Yung into massive debts, which he couldn’t afford to pay. There was only one way out: he took out another bank loan, and reopened shop in a busier part of the city. There, he quickly gained a new following, thanks to his winning formula of cheap prices and personalized care.

Over the next two years, the Garage grew into one of Seoul’s greatest auto repair shops. With over 70 employees, Yung was doing better than ever.

When Fascist Japan invaded Korea in 1942, the new colonial government confiscated Yung’s service garage. The business was merged with a steel plant, in order to fuel Japan’s industrial murder efforts. Tensions were high, and Yung was forced to return yet again to his home village.

Despite losing the car shop, Yung had managed to save up 50,000 wun. He used these funds to start up his new venture.

Birth of Hyundai

When WWII came to an end, Korea gained its independence from the Japanese Empire. With no more government interference in business, Yung was able to restart his auto business in 1946. It was called Hyundai Auto Service Center. In English, the word Hyundai translates to “modern.”

Yung’s first customers were Japanese people and US military trucks. By the end of the year, business had grown so much that Yung’s network nearly tripled from 30 to 80 people. Once again, the Korean businessman demonstrated his entrepreneurial chops. This time, his excellence could not be abated by government obstruction.

By this time, Yung had brought his family to the newly established country of South Korea. Inspired by the high wages of construction workers, he founded his own construction company in 1947. It initially struggled. It built US Army quarters and auxiliary sites, as well as building repairs.

By 1950, the Hyundai company was making progress.

Goryeong Bridge

When North Korea invaded its southern neighbor, Yung was forced to abandon his business and evacuate to Busan. Penniless, he was again left to work a merry-go-round of changing jobs, such as publishing and newspaper delivery. Korea’s newspapers spread word that the UN was on the way to liberate the South from the invaders. It was their only hope for freedom.

One day, Yung stumbled upon a “help wanted” sign of the US Army. At the time, US forces were in need of local construction experts. Yung was eager to help. He began building barracks for thousands of American troops. It was the start of a very constructive business relationship with the US Army. Bigger and bigger projects followed. He remodeled a US quarter in South Korea, and built a lodging for US presidents visiting the country.

By the war’s conclusion, Chung’s commercial enterprise was in first place to hand orders from the US Army. Ravaged by the invasion, South Korea was left as one of Asia’s poorest nations, even below that of North Korea. In response, the US provided billions of dollars to reconstruct the South’s economy. Chung saw the opportunity to negotiate a lucrative contract with the US. He helped rebuild South Korea’s Goryeong Bridge in 1953.

However, Chung had bit off more than he could chew. He lacked the knowledge, equipment, and safety regulations for such a massive task. Workers died from accidents. Progress was slow. The country’s skyrocketing inflation chewed away at his budget. Running out of money, he was forced to take out more loans. His brothers even sold off their houses to help finance workers. In spite of these setbacks, construction continued to take place until the bridge was completed. But by the end, Yung and his family were left humiliated and out of cash. Seeing his brothers reduced to destitution, Yung renewed his efforts for financial stability. He vowed to create the biggest company the country had ever seen.

“I had no intention whatsoever of abandoning my business,” he later recalled. “I had failed because I was lacking and in need of more experience. However, I brushed it off and simply thought of it as an expensive lesson.”

Rebuilding South Korea

The Goryeong disaster would have positive effects as well. Hyundai received a high credit score from South Korea’s Ministry of Interior, which allowed him to gain sizable loans for expanding his business. He acquired essential knowledge about heavy equipment and advanced machinery. Thanks to his partnership with the US Army, Yung was able to directly purchase many of his needed supplies. At the time, this type of equipment was monopolistically owned by South Korea’s government; private business were banned from importing them overseas. This gave Yung a huge advantage over his business competitors.

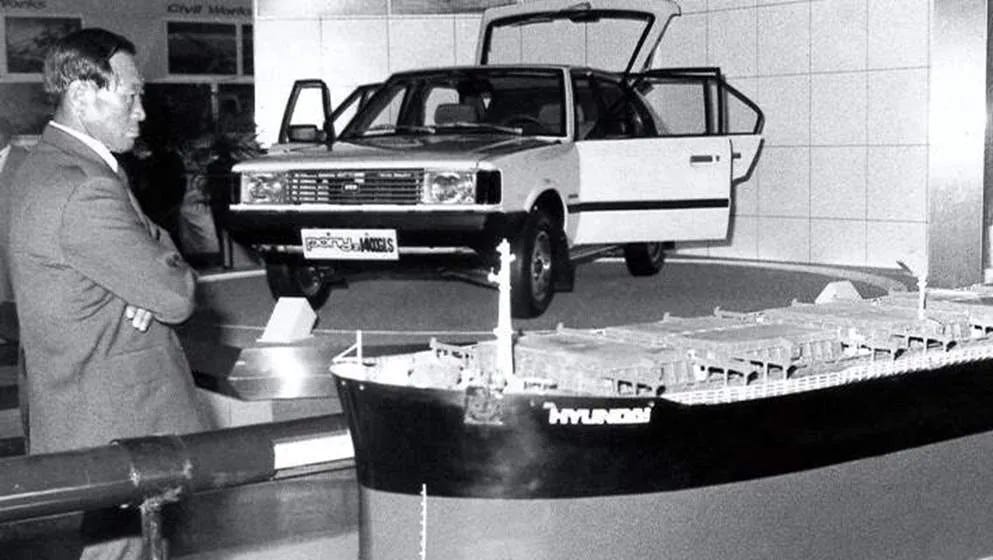

Under Yung’s direction, Hyundai took an active role in constructing roads, bridges, dams, and buildings in post-war South Korea. Hyundai was a jack of all trades, producing a vast array of industrial products. This included ships, store chains, and electronics, as well as offering financial services. All of this activity turned the company into one of South Korea’s most powerful business entities. With his newfound power, Yung took Hyundai beyond South Korea into the international market. He rapidly rose to become one of the largest firms in the industry, raking in billions of dollars from overseas projects. This included Saudi Arabia’s Jubail Industrial Harbor and Bahrain’s Arab Shipbuilding and Repair Yard.

By 1960, Hyundai had risen to become a major competitor in the auto industry. In a span of two decades, Yung’s Hyundai company went from a failing business into a vast global conglomerate. But this is not solely because of Yung’s acumen. His company received plenty of special privileges handed out by South Korea’s government, including financial subsidies, loan guarantees, and tax breaks to grow and diversify the company. Nevertheless, Yung’s relentless entrepreneurship made him one of the country’s most competent titans of industry, and the government knew it.

Hyundai Motors

In the 1960s, South Korea’s government adopted a new policy that forbade foreign automakers from operating in the country, unless they engaged in joint ventures with local business. This policy ensured that the Koreans would gain valuable knowledge about the production of cars. The county largely lacked the technology and resources to start an auto industry without foreign assistance.

Seeing the opportunity, Chung decided to reenter the car market. He founded the Hyundai Motor Company in 1967. Yung struck a deal with Ford, licensing the use of their vehicles and setting up a large assembly plant in Ulsan.

The Cortina

In less than six months, the Hyundai Factory was completed. They released their first car, the Hyundai Cortina. It was no different than the Ford Cortina, which was popular in Britain. While the model was a success in Britain, it was failure in South Korea. Cortinas were designed for asphalt, but Korea’s poor roads made these cars impossible to drive. The Cortina became a laughing stock, mocked ruthlessly by the Korean populace. Customers stopped making payments, and angrily demanded refunds.

To make matters worse, Hyundai was struck by severe floods in September of 1969. Four feet of rainwater inundated and submerged the factory. Rumor held that the company was selling water-filled Cortinas, which further damaged Hyundai’s reputation and sales. It was brought to the brink of bankruptcy.

Chung refused to cave in. “I’ll never take down a single Hyundai sign with my own hands,” he declared defiantly. “Even if a business is struggling and everything seems hopeless, I will make it work. If I start something, I’m going to see it through.” For the next few years, Yung continued to produce vehicles.

The Pony

As time elapsed, South Korea began to improve its roads. So did the reputation of the Cortina, which saw increased sales. It was not long before another Ford model would be brought to Korea.

Ford was growing more frustrated by Hyundai. The American company didn’t like that Korea was selling its Cortinas abroad, and it refused to share its profits with Hyundai.

Chung was dissatisfied for his own reasons. He felt that Ford was merely using his company as a puppet to acquire cheap labor. Furious, the Korean titan terminated the contract in 1974. He was now determined to build his own car, on his own terms.

After breaking ties with Ford, Chung set up a new relationship with Mitsubishi. He wanted to appropriate their engines and rear axles. Yung hired a group of talented European engineers to design Hyundai’s next vehicle: the Hyundai Pony.

The Pony was able to move along unpaved roads, and it sold for the affordable price of $5,900. It became an instant success in South Korea, becoming the country’s first mass-produced car. It performed so well, that four out of every ten cars were Ponies.

Now bolstered with confidence, Chung and his team began to export their model to the global marketplace. They sold quite well, and were especially popular in Canada. The Pony did not appear in America, because it failed federal emissions standards.

The Excel

In 1985, Hyundai released their Excel model. This time, it successfully passed American emissions standards. Finally, Hyundai was able to break into the US auto market.

Sold at just $4,995, the Excel was half the price of a typical new car. It sold 168,000 in the US alone; a million more Excels were sold worldwide.

The Excel was a major breakthrough for Korea’s car industry, with Hyundai at its helm. Despite this, Chung’s company lagged behind other brands in terms in quality and reliability.

The American public derided them as cheap Korean knockoffs with barely any features. Hyundai’s cars earned an unglamorous reputation for frequent breakdowns. Their sales plummeted, with Hyundai becoming little more than an American punchline. Americans joked that Hyundai stood for “Hope you understand nothing’s drivable and inexpensive.”

Quality cars

To turn itself around, Chung and his company worked tirelessly to produce their own engines and auto parts. Going into the 1990s, Hyundai produced another string of models, including the Accent, the Sonata, and the Elantra. While these models struggled to gain sales, they eventually caught up to other brands through their innovative car features.

Hyundai went on to acquire Kia Motors in 1998. This joint venture marked a turning point in Hyundai’s history. By 2004, it had risen to the point of tying Honda as having the second-best initial brand quality in the industry—just behind Toyota.

In his later years, Chung devoted himself to philanthropy. He ran for president. Using his stature as a globally respected businessman, he attempted to negotiate a rapprochement between the two Koreas. Chung died in 2001, leaving control of the company to his sons.

Even with their modern reforms, Hyundai continued to have a reputation for cheapness. So they announced a new policy of providing ten years of warranty for hundreds of thousands of miles on all vehicles sold in the US. Thanks to this, sales rose rapidly. Hyundai is now one of the leading car brands of the 21st century.