Hannibal vs. Rome: The Second Punic War

How one Punic general nearly brought Italy to its knees.

In the second of three Punic Wars, Rome was brought to near extinction at the hands of its bitter rival, Carthage.

Carthage in Spain

Since the end of the First Punic War ended in 241 BC, Rome had gained possession of Sicily. But Carthage, while bruised, was far from defeated. Carthage still held the coast of North Africa, from Morocco to Libya. Carthage still had a voracious appetite for conquest. The only question was which way to expand.

The First Punic War had blunted Carthage’s northward expansion. To the south, there was only the empty wasteland of the Sahara Desert. To the west was the Atlantic Ocean. To the east was the powerful Hellenistic kingdom of Egypt.

The logical choice for Carthage was to move across the Strait of Gibraltar into Spain. Carthage had long held several outposts along the Spanish coast. They sought to use those posts to expand further into the peninsula. The leader was Hamilcar Barca, who had successfully led Carthage’s war efforts in Sicily, until he was betrayed by the lack of support from his own government. He now applied his military skills to subdue the Celtabarian tribes of Spain.

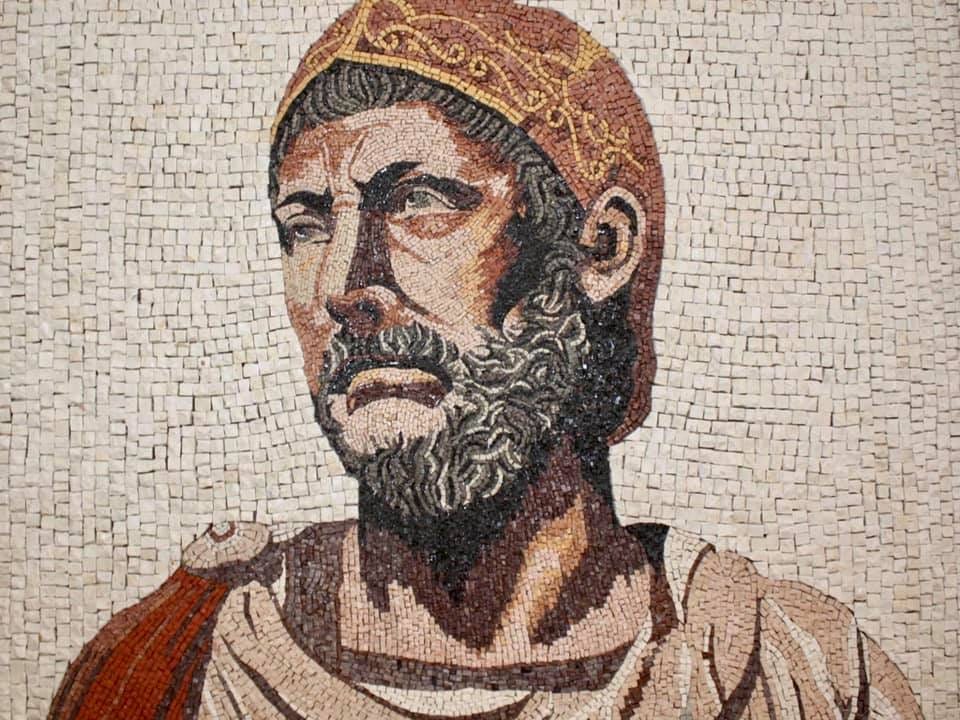

Hamilcar established what amounted to a personal empire in Spain. The tribal people were useful recruits, and he amassed a formidable army to inflict revenge against Rome. Hamilcar died in 229 BC, probably while crossing a river during a military expedition. This left command to his 26-year-old son, the legendary general Hannibal, who continued his father’s work. Despite his young age, Hannibal was already displaying his gifted military genius.

Post-war Rome

Meanwhile, the Romans overcame their fear of the Gauls, and expanded northward at their expense. They defeated the Gauls at the Battle of Telamon in 225 BC, adding the Po River valley to their territory.

As Carthage expanded northeast from Spain, the Romans advanced from the southwest from Italy. Another collision between the superpowers seemed imminent. Again, the locus of conflict was determined by geographic concerns.

War was nearly averted by a peace treaty, where Carthage promised not to advance north of the Ebro River. Southward was the town of Saguntum, which signed an agreement with Rome. Saguntum raided some nearby territories, which belonged to Hannibal and Carthage. In retaliation, Hannibal inflicted his wrath on the town. Rome decided it had to come to the aid of its ally. The Second Punic War began, in 219 BC.

Carthage was enraged, viewing Rome as unfairly meddling in its own Punic sphere of influence. Rome, by contrast, saw itself as accepting the invitation to defend an ally. Saguntum deserves some blame too, because it entered a provocative alliance with Rome, and it foolishly raided into Punic territory. The mismanagement of the three powers led yet another war.

Hannibal’s war

At the start of the war, Rome appeared to have the advantage. Rome’s army enjoyed an endless supply of manpower from the Italian mainland. Even at sea, Carthage no longer enjoyed its monopoly on naval power. Despite these initial advantages, Rome was nearly wiped off the face of the Earth in this war. This was because, this time, Carthage had a secret weapon: Hannibal.

Hannibal knew that Carthage couldn’t defeat Rome in a traditional conflict. He couldn’t wait for Rome to take the initiative. He also knew of Rome’s manpower advantage, thanks to its Italic allies Hannibal felt that, somehow, he had to cut off Rome’s vast supply of manpower reserves. He embarked on a bold plan: to invade Italy itself. If he could win a few decisive victories on Roman soil, Hannibal reasoned, the other Italians would revolt against their Roman master.

There was a practical problem on how to get there. Hannibal couldn’t use the sea, because of Rome’s now-powerful fleet. The only choice was to march from Spain, across the Alps, down into Italy. The Alps were a dangerous option. They were icy. There were landslides. They were filled with murderous tribal people. It was believed to be impossible to cross the Alps. But not for the mighty Hannibal!

In early May of 218 BC, Hannibal and his 40,000 troops, and 37 elephants, crossed the Alps. Incredibly, he made it! But only 26,000 men survived, and only one elephant. The Romans were shocked and alarmed by Hannibal’s surprise attack. They quickly whipped together 40,000 men under the command of both consuls to fight Hannibal.

At the Battle of the Trebia, in 218 BC, Hannibal’s genius shone. He craftily lured the two Roman commanders into a fatal trap. The Romans were badly beaten. The next year, in 217 BC, the Romans hastily assembled yet another army to hunt down Hannibal. Hannibal again surprised the Romans. He moved through the marshlands of the Arno River. He lost sight in one his eyes, due to the swampy conditions.

Having broke into Italy’s heartland, Hannibal raided towns and destroyed farms. The Romans rushed after him. Hannibal lured them into the foggy shores of Lake Trasiemene, where his Punic troops pounced on the unprepared Romans. The Romans were butchered by Hannibal’s calvary, and many of them drowned in their hasty retreat.

Battle of Cannae

The Romans were more alarmed than ever. They turned to Fabius Maximus, a seasoned general who was appointed Rome’s dictator. Fabius decided on a new strategy. He cautiously avoided any open battle with Hannibal’s men. It was a war of attrition. The Romans took advantage of the time to amass large armies. But Rome came under the influence of hot-headed politicians, who decided to overwhelm Hannibal with a larger-than-life army. They wrongly believed that numerical superiority would result in an inevitable triumph against Hannibal, apparently not realizing Hannibal’s military prowess. A colossal Roman army of 80,000 men marched out, led but by both consuls.

By this point, Hannibal had made his way into south-central Italy. The Romans caught with him on August 2, 216 BC. This became the notorious Battle of Cannae, which showcases Hannibal’s unprecedented military leadership skills. Most ancient armies fought by placing their best troops in the middle, and their cavalry at the sides. The Romans coalesced their masses of heavy infantry into a deep block, with small cavalry units on the flanks. Their strategy was simple. The Romans believed their horde of men would pummel Hannibal’s forces through brute force. Hannibal outsmarted them. His formation slowly and cleverly engulfed the unsuspecting Romans, who had wrongly thought they had won the battle. In a single battle, Hannibal’s men crushed 65,000 Romans. It was one of the bloodiest days in military history. More Romans died in this single day than Americans in 20 years of Vietnam. Even Gettysburg was only 15% of the Roman losses at Cannae.

Hannibal’s unique strategy of double envelopment has since been widely imitated. It was the basis of Germany’s Schlieffen Plan in WWI. The Nazis were inspired by it. In the Gulf War, Norman Schwarzkopf invoked Cannae as his model.

The Battle of Cannae was one of the darkest moments in Roman history. Rome panicked. Hannibal seemed to be an invincible enemy. The Punic general marched to Rome’s gates, but the Romans barricaded themselves and refused to surrender. Hannibal, lacking supplies for siege, begrudgingly retreated in order to keep his men feed.

Fabian strategy

After the disaster at Cannae, the Romans returned to Fabius’ strategy. The Romans raised new armies, but strictly avoided battle. They were determined not to give Hannibal the opportunity to kill more Romans. The Fabian strategy was a brilliant one. Hannibal continued to wander aimlessly, forced to scavenger for food. Everywhere he went, so did the Romans. Fabius became known as Cunctator (“the delayer”).

Hannibal had invaded Italy, and won decisive victories on Roman soil. There was only one part left of his plan. He hoped that Rome’s Italian allies would exploit Rome’s weakness and revolt. He counted wrong. In the aftermath of Cannae, some Italian states defected to Hannibal. Usually, they were the more recent additions to Rome’s Republic. But the vast majority of Italians stayed faithful to Rome. Rome’s policy of generosity and inclusion finally bore fruit. Hannibal’s plan became a massive failure. He was stuck roaming up and down Italy, looking for someone to fight. This went on for 12 years.

Scipio

Rome raised more armies, which it summoned to Spain. Roman command fell to a young man named Scipio, who was something of a military genius himself. He conquered Carthage’s provinces in Spain. The water was just shallow enough for Scipio to climb over the unguarded walls. Scipio came to be seen as favored by the gods, a view the general encouraged among his men.

Hannibal’s brother, Hasdrubal, brought reinforcements to Hannibal. Had they arrived, Rome might have been vanquished. But the Romans intercepted and destroyed them. The Romans beheaded Hasdrubal, and threw his severed head over the walls into Hannibal’s camp. He was devastated.

By 206 BC, Scipio had destroyed the rest of Carthage’s Spanish holdings. Two years later, in 204 BC, Scipio led an invasion of North Africa. Jealous senators refused to supply Scipio, but Scipio simply called up volunteers, who happily obliged his request. In Africa, he picked up even more allies, notably the powerful Kingdom of Numidia. With Numidia’s help, Scipio marched toward Carthage. Carthage recalled Hannibal from Italy to defend the city. Despite winning every single battle, in spectacular fashion, a humiliated Hannibal was forced to withdraw from Italy.

Hannibal and Scipio engaged in an epic showdown at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. Scipio’s army was well-trained and out for blood. Hannibal’s men were demoralized and exhausted. For the very first time, Hannibal was defeated. Carthage surrendered in 201 BC, bringing the Second Punic War to a close.

A Carthaginian peace

This time, Rome was determined not to have another war. Carthage was forced to pay 10,000 talents over 50 years. Carthage had surrender almost all of its territory. The city itself was only permitted to keep a small army and a token fleet of 10 ships. Numidia became a Roman client kingdom. Parts of Spain and North Africa were reorganized as Roman provinces.

In order to defeat Hannibal, the Romans had been forced to professionalize their army. Soldiers served year round under Scipio. They were supplied with new equipment and tactics, including a new sword. When in Spain, Scipio had been impressed by the shorter swords of the Spanish tribes. The Roman gladius, as it came to be called, soon became a symbol of Roman imperialism.

Scipio received a lot of dignitas, and was hailed as Rome’s savior. He gained the sobriquet Africanus, meaning “conqueror of Africa.” For the first time, the balance of Rome’s aristocracy tilted in favor of just one man: Scipio and his family.

After the defeat at Zama, Hannibal became a politician back in Carthage. Tired of war, the former general became a tireless advocate of peace. He tried to reform Carthage’s corrupt government. His efforts were successful in wiping out nepotism. When rumors spread that Hannibal was planning yet another war against Rome, the Romans came back to Carthage to arrest him. The Punic general evaded their custody, and fled to the Hellenistic Kingdom of Syria, ruled by Antiochus III. Antiochus, who was at war with Rome, made Hannibal an admiral in his navy. He then became an adviser to the eastern Kingdom of Bithynia, another enemy of Rome. In 183 BC, the Romans caught up with him. Tired of running, and now in his mid-60s, Hannibal committed suicide by drinking poison.