Growing up is hard at any time, but it was especially so in ancient Rome.

Birth

First of all, you’d be lucky to be born at all in Rome. Remember, this was before the Industrial Revolution and modern medicine. One in three babies died before the age of 1. When you factor in childhood diseases, 50% of Roman kids died before reaching puberty.

When a baby was born, it would be placed on the ground in front of the father. The father, or pater familias, exercised near-absolute authority over his family, including the right to have his kids executed. If the father didn’t want the kid, he could simply order the baby be left outside. The baby would be named after 8 days (for girls) or 9 days (for boys).

The Romans felt that, in order to produce strong soldiers, they couldn’t coddle their kids. They were bathed in cold water. Babies were tied tightly in cloth. This was done to ensure the baby came out right-handed, since left-handedness was associated with misfortune. Babies’ heads were kneaded by nurses into a pleasant round shape.

A Roman man instructed his wife to breastfeed not only his own biological kids, but also his slave kids. This was done to ensure the loyalty of slaves into adulthood. Babies suffering teething pains had sheep’s brain rubbed onto the gums, which was thought to reduce the pain. Sometimes, they’d be given a gritty substance taken from the horns of snails.

Childhood

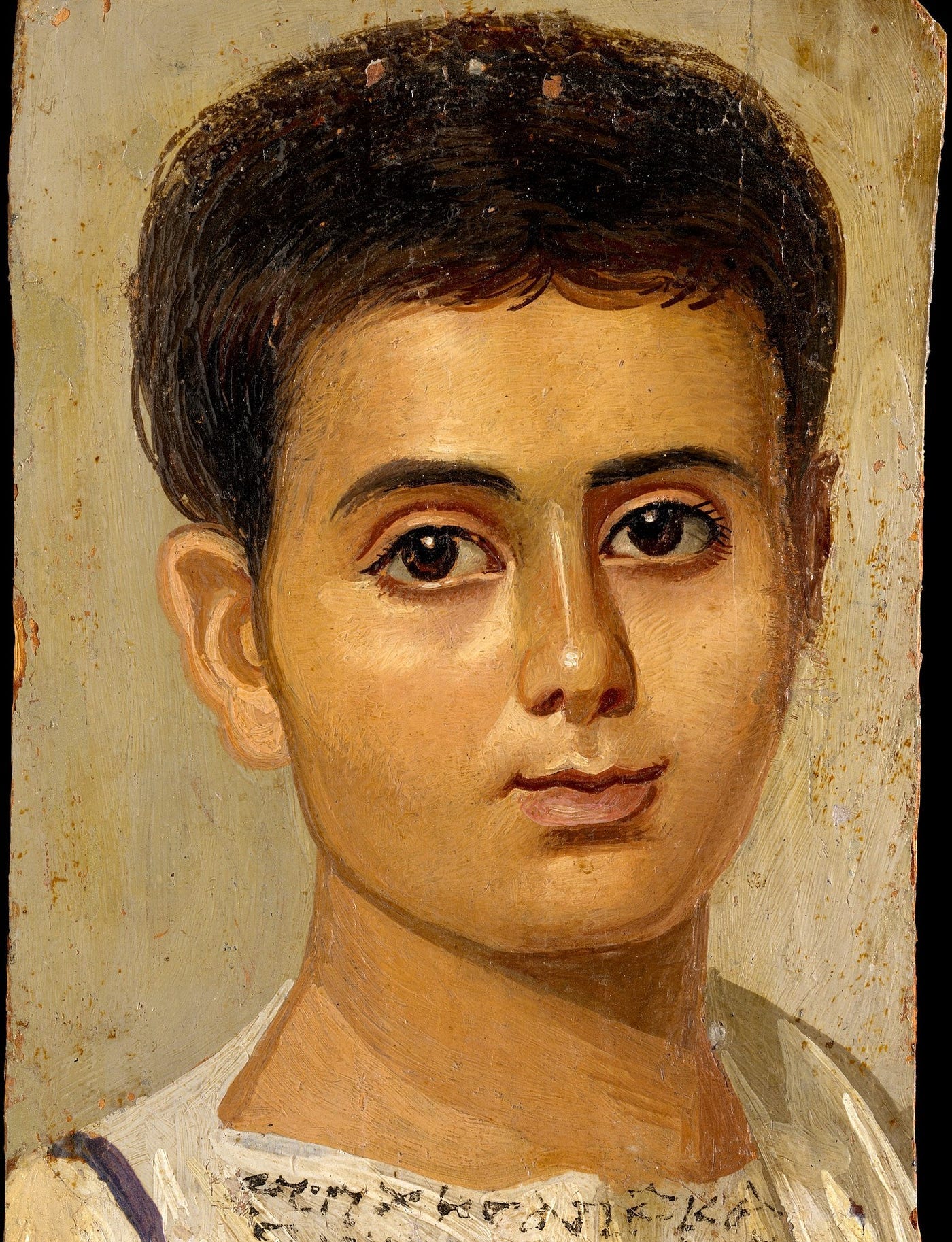

Roman law defined childhood as before the age of 12 for girls, and before the age of 14 for boys. A Roman boy was known as a puer, who wore a distinctive mini-toga with purple-striped edges, called the toga praetexta. Roman boys were usually given a leather bag filled with magical amulets, called a bulla. It was worn at all times around his neck. Ordinary Romans were superstitious people, and they believed children were susceptible to evil influences. To toughen up the boys, they were forbidden from eating lying down, which was the mark of adulthood. They were not permitted to get much sleep, because it was feared to stunt intelligence and growth. A girl was called a puella. The term was also used for women who hadn’t given birth, or were still virgins.

Until the age of 6 or 7, boys and girls were raised together in the family. This included the slave children, who played together with their free masters. Roman boys and girls played with a variety of toys. Ball games and playing with hoops were popular. Kids built sand castles, spun tops, and skipping rocks across water surfaces. Children played with small clay, wood, or even bronze figurines. This included representations of animals, soldiers, and gladiators. Dolls were made of wood and ivory. Birds, dogs, and rabbits were kept as pets. There were games of chance, using spotted dice or animal bones. Romans of all ages enjoyed playing board games, which resemble modern-day backgammon. Some of these games were carved into the steps of public buildings.

Education

Education was led by the father, who taught his sons practical skills for living. This included basic literary and military training. More formal education was reserved for the male offspring of Roman elites. Girls were instructed in domestic chores, such as spinning and weaving.

Roman education was revolutionized after Rome’s conquest of Greece. Exposure to Greek literature and culture raised the expectations of a Roman liberal arts education. Aristocrats were expected to know Greek and Latin, know the literature of both cultures, and give public orations. The hundreds of thousands of enslaved Greeks provided a supply of teachers. Roman students cycled through various teachers. The goal of a Roman’s education was to produce an eloquent speaker.

1) Latin and Greek

Roman children were instructed by a teacher called a pedagogus, an educated household slave who taught Latin and Greek. His main duty was to look after the child, and accompany him in public. These teachers were also tasked with disciplining unruly children, usually by twisting the ear or whacking with a cane. There are many cases where the Roman, after reaching adulthood, would release his old teacher from slavery out of gratitude.

2) Literature and Grammar

Formal education began around age 6 or 7. The new teacher, called a litterator, was a tutor who signed contracts with the child’s parents. Reading, writing, and arithmetic were the subjects. A more advanced tutor was called a grammaticus.

On a typical school day, class began at dawn. The boy had to get up long before this, get dressed, eat a simple breakfast, and walk to school with his pedagogus. There were no actual school buildings. A teacher could rent a shop or an apartment, or else set up a school at a forum or in a colonnade. The teacher sat on a throne-like chair, while the kids sat on simple benches. There were no chalkboards or paper. Instead, students wrote a small, wood-encased wax tablets. They scratched letters into the wax using a metal stylus. There was no official schedule for school. Classes usually ended for the summer, lasting from early June to October. Students were punished by having their hands whacked with a reed cane. The worst offenses were punished by flogging, using a leather whip. But there were some Romans, such as the influential rhetorician Quintilian, who emphasized positive encourage over draconian punishments.

3) Rhetoric and Liberal Arts

The last couple of school years focused on literature, particularly on the works of Homer and Virgil. This phase of education ended around the age of 13.

There was no college or university, but the brightest of Rome’s students could receive additional training by a teacher called a rhetor. This education focused on rhetoric and oratory, essential skills for a life in Roman government or military. The art of persuasion was highly valued by the Romans. Some Romans disliked the idea of an advanced liberal arts education. These ultra-traditionalists, such as Cato the Elder, dismissed it as a carryover from Greek culture. Cato personally oversaw the education of his son, teaching him such skills as literacy, law, javelin throwing, boxing, fighting on horseback, and swimming.

Graffiti, written by non-elites, suggests that the average Roman was at least reasonably literate. Soldiers learned to write, and they wrote letters to their loved ones while campaigning.