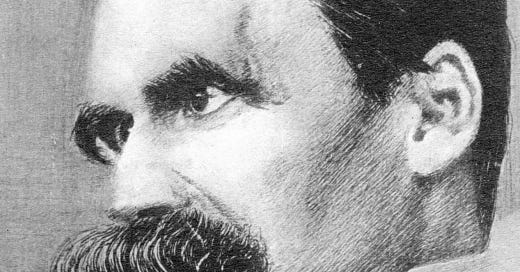

His mustache speaks for itself. The fearless and powerful Nietzsche was one of the most influential thinkers of 19th-century Europe. The German philosopher spoke of such strikingly original concepts as the death of God, the will to power, master-slave morality, the herd instinct, the Übermensch, and the transvaluation of values.

But beneath the facade of ballsy machismo lies a deeply sensitive, thoughtful man, who explored deep questions and gave even deeper answers. He examined life’s most important dilemmas with his laconic wit and larger-than-life charisma. Nietzsche placed Western philosophy on an entirely new, unprecedented foundation.

For him, philosophy was not just dumb words on a dusty page. It hinged on the central question of human existence: the deeply personal need to find meaning in a seemingly indifferent and cruel world.

Nietzsche’s existential ideas were forged in the cauldron of his own personal suffering and anguish. He agonized from his poor physical health, as well as the extinguishment of his brilliant mind in his latter years. Yet in spite of this, the brilliant Superman spent a lifetime grappling with the problem of human tragedy, and how to cope in a world filled with more tears than triumphs.

Early life

Nietzsche was born on October 15, 1844 in the small Prussian town of Röcken. It was the birthday of the Prussian King, Friedrich Wilhelm IV. The monarch became Nietzsche’s namesake.

Nietzsche came from a devout Lutheran family. His father was a working minister, while his mother was a typical Christian homemaker. From an early age, he enjoyed the solitude of reading the Bible. He was referred to by his peers as “the little minister.”

When he was aged 5, Nietzsche’s father died of brain damage. His mother moved the family to Naumburg, when young Friedrich attended a private prep school. After this, he went to the most prestigious boarding school in all of Protestant Germany. He graduated in 1864, and continued his studies at the University of Bonn, where he took up classical philology and theology.

Education

Shortly after beginning his time at Bonn, Nietzsche abandoned the fervent faith of his childhood. This was the result of his intense devotion to truth and higher knowledge. “If you wish to strive for peace of soul and pleasure, then believe,” Nietzsche wrote to his sister. “If you wish to be a devotee of truth, then inquire.” He did not have a single de-conversion experience, but it was the gradual evolution of his thought.

Friedrich fell in love with the pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. “It seemed as if Schopenhauer were addressing me personally,” the German Superman once opined. The youthful and brilliant Nietzsche clashed with his professors. In 1865, he decided to transfer to the University of Leipzig. There, he received acclaim from his peers and teachers alike. Nietzsche’s studies were interrupted when, in 1867, he spent a brief time in the military. He injured himself after trying to mount a horse in 1868. The German philosopher made his way to the University of Basel, where he pursued his love of the classical languages. By 1870, he rapidly rose to the rank of a full-fledged professor.

Birth of Tragedy

Nietzsche met the famous German composer, Richard Wagner, in 1868. He also met Wagner’s mistress, a woman named Cosima. This began the Superman’s lifelong bromance with the epic German composer. Nietzsche often compared Wagner to the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus. He spent a lot of time visiting his musical friend, even spending Christmas together in 1869.

Nietzsche’s reverence for Wagnerian music inspired the Superman to write his first book, The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music.

Just as he begun to travel to the Alps to write, Nietzsche heard news of war between France and Germany. Despite his wishes, the philosopher’s failing eyesight ensured that he would not become a German soldier yet again. To make matters worse, he fell ill with dysentery.

He found himself back at Basel by October of 1871. Nietzsche’s scholarly duties were too much for the man’s failing health. So he applied to the vacant chair of philosophy.

Nietzsche, now aged 27, was prepared to publish his first book, The Birth of Tragedy. It was initially received as an unexceptional, hackneyed work of classical scholarship. His contemporaries accused him of ignorance, distorting facts, and drawing false parallels between the Greeks and the modern world.

Soon after Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, Wagner moved away to Bayreuth. The German philosopher became increasingly uncertain about the value of Wagner’s music. He became concerned about the state of German culture and music. This was discussed on his Untimely Meditations. After attending a Wagner festival, Nietzsche made a break with his musical mentor.

Health issues

As Nietzsche’s health further deteriorated going into the 1870s, the Superman stepped down from his educational duties. He began living with his sister Elisabeth. She got married to an anti-Semite, and planned to move to Paraguay to establish a communistic community. She begged her brother to go with her, but Friedrich was too infatuated with European culture to leave the continent.

Around this time, Nietzsche was preparing to publish his book Human, All Too Human. It was the largest work of his entire oeuvre, with a massive 638 sections. Following its publication, the Superman’s health continued to worsen. This forced him to give up his coveted chair at the University of Basel in 1879. In that year alone, he reported 118 days of migraines.

Nietzsche was no longer able to perform tasks beyond a minimum effort. Around this time, he caught syphilis from a prostitute.

By the end of the year, Nietzsche was suffering in both mind and body. Preparing himself for death, the strong-willed German thinker told a friend, “See that no priest or anyone else utter falsehoods at my gravesite.”

But he managed to make a miraculous recovery, spending the next decade moving between small towns in Northern Italy and the Swiss Alps.

Love of Fate

Nietzsche’s recovery in health coincided with a greater optimism in his philosophy. He spoke more happily about the idea of Fate. “My formula for life is amor fati,” he boldly proclaimed, “not only to bear up under every necessity, but to love it.”

With better health, the Superman began to write with a vigorous and renewed passion. In 1880, he wrote Daybreak. He wrote The Gay Science in 1882, where he famously proclaimed that “God is dead, and we have killed him.”

Friedrich was slowly making his way toward the pinnacle of his ground-breaking philosophy. Shortly before Christmas of 1882, he met a woman named Lou Salomé, whom he deeply loved and admired. The Superman was lovestruck by her. With the help of his buddy Paul Rée, the German Übermensch attempted to propose to the woman of his dreams.

Nietzsche hoped that she would reciprocate his passion, but it was not to be! Although she did not outright reject him, it became increasingly clear that the Superman would not be her amorous lover. To worsen this humiliation, Lou favored his friend Paul as her desired husband.

“This last morsel of life was the hardest I have yet had to chew,” the German philosopher bitterly lamented, “and it is still possible that I shall choke on it… Unless I discover the alchemical trick to turning this muck into gold, I am lost.”

Thus Spake Zarathustra

Filled with unrequited passion and rage, he fled to the Swiss Alps in 1883. Just as Wagner died, the Superman published his book Thus Spake Zarathustra. He regarded it as his masterpiece. “This work stands alone,” Friedrich gloated boastfully. “If all the spirit of goodness of every great soul were collected together, the whole could not create a single one of Zarathustra’s discourses.”

Although today considered a classic of the Western Canon, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra was met with a lukewarm reception among the academics of his day. Paying for the publication himself, he managed to sell a meager 40 copies. Seven more were given away for free.

The book’s failure was a crushing blow to Nietzsche’s already fragile state of mind. But the Superman persisted on. With his eyesight still in decline, he began to write only in short, pithy phrases—called aphorisms. He regarded these later books as commentaries on Zarathustra, which the German considered his magnum opus. Beyond Good and Evil and The Genealogy of Morals soon followed.

Final years

In 1888, the final year of Nietzsche’s sane life, the German thinker continued to write furiously and productively. Among these later works include Twilight of the Idols, Anti-Christ, The Case of Wagner, Ecce Homo, and The Will to Power. Although these classics of Nietzschean philosophy were all penned around the same time, they were episodically published over a span of almost two decades.

Sometime in January of 1889, Nietzsche collapsed suddenly in the streets of Turin. When he awoke, he rushed home and wrote ambiguous letters to his friends. It was enough to cause concern. Nietzsche was found seated at his piano, striking at the keys with his elbows and singing incoherently.

The Superman’s mental state became increasingly erratic and unstable. His physical health continued to collapse. The German philosopher was brought Basel, where he was held at an insane asylum. He was taken into the care of his mother soon after.

Nietzsche died on August 25, 1900. He probably died of the syphilis that he had contracted back in 1870. More recently, some scholars have argued that the German thinker died of degeneration of his cerebral blood vessels, perhaps the same condition that killed his father.

Legacy

The Übermensch’s philosophy is often viewed in sinister connection with the Nazi Party. However, this is because his sister Elisabeth, who had married a rapid Jew-hater, manipulated—and sometimes even fabricated—her brother’s works. Despite the deliberate attempts by Hitler and his genocidal regime to appropriate the mantle of the German Übermensch, the connection is tenuous at best. Nietzsche remains a fiercely independent and individualistic figure—in stark contrast to the intolerable conformism of the Third Reich.

Today, Nietzsche’s ideas continue to inspire and permeate modern pop culture. His refreshing and boldly original insights have rightly solidified the Übermensch’s status among the pantheon of Western thinkers.

Learn More