John Dillinger was one of the most notorious and dangerous criminals during the Great Depression. His thuggish thievery began what would be the opening salvo of America’s War on Crime. Led by J. Edgar Hoover, the Federal Bureau of Investigation mounted a nationwide campaign against violent crime. Guided by cutting-edge science and police forensics, it would be a turning point in the history of modern crimefighting.

Thug life

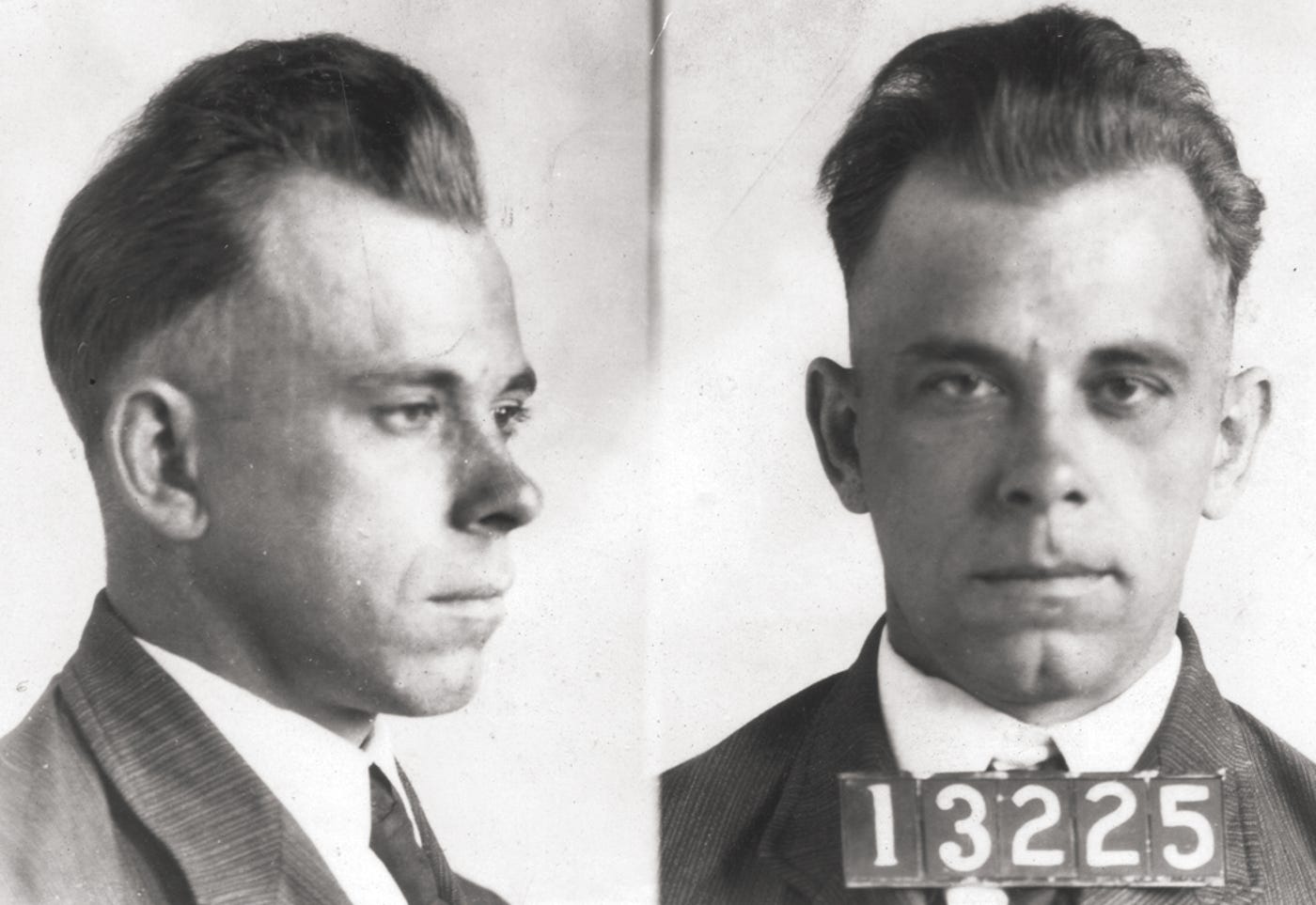

Dillinger was born in 1903. He lost his mother at an early age, leaving him under the paternal despotism of his father. Suffering a troubled adolescence, he enlisted into the Navy, but later deserted. Unemployed, the 21-year-old mugged a grocer in his hometown outside of Indianapolis. The delinquent youth was sentenced to a decade in prison. While in jail, Dillinger was exposed to some of the worst criminals in America. Traumatized by the experience, he vowed to inflict revenge. He sought a life as a bank robber, in order to raise enough money to purchase weapons and break out his prison buddies.

Great Depression

From 1929 to 1933, America’s industrial production dropped in half. 13 million Americans were thrust into unemployment. When Roosevelt became president in 1933, a full quarter of the working population was without jobs. Two million were homeless. Hungry marches grew larger and more numerous. Demonstrations took place across the nation’s largest cities. Workers went on mass strikes. Many Americans blamed the banks for their financial hardship. Because of this animosity toward the banking establishment, much of the public was actually sympathetic to John Dillinger’s thievery. In the popular consciousness, he became an unlikely hero to an entire generation of Americans. Dillinger was not only infamous for his crimes, but also his ability to evade justice. On one occasion, he was arrested while visiting his girlfriend in Dayton, Ohio in September of 1933. His criminal friends broke him out of jail, murdering the sheriff in cold blood. Together, they formed the very first Dillinger Gang. During the Depression, many women turned to a life of crime out of economic necessity. They became romantically involved with bank robbers, in exchange for security and protection. But some women were generally criminals themselves, such as the excitement-hungry Bonnie Parker.

War on Crime

Dillinger’s criminal activity had a dramatic impact on the history and development of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. In a span of eighteen months, Dillinger’s high-profile robberies transformed the FBI’s first Director, J. Edgar Hoover, into a household name. Poverty was at its worst in the Great Plains, which stretched north to south across the middle of America. The region spanned from the Rockies to the Mississippi River. As depicted in Steinbeck’s famous novel Grapes of Wrath, many people in Oklahoma migrated to California in search of of work. The remote Great Plains provided an ideal getaway for bank robbers and criminals. Deserted roads could be driven at 200 miles an hour, which was perfect for criminal escapes. The War on Crime began with the Kansas City Massacre in June of 1933. An outlaw named Frank Nash was arrested by FBI agents in Arkansas, and took him back to Leavenworth prison. But as the FBI agents were ready to put Nash on the train, they were assaulted by a flurry of Tommy gun fire. Six agents were killed. This led the Attorney General and J. Edgar Hoover to declare America’s first-ever War on Crime. They vowed to hunt down the bank robbers and bring them to justice. But this mission would be much more difficult than they anticipated.

Modern policing

Amid the Kansas City Massacre, Dillinger was released from prison in May of 1933. He immediately began robbing banks. At the FBI headquarters in DC, Hoover grew increasingly concerned about the bank robberies, as well as the inability of local police to stop them. Crime had been on the rise since the 1920s. New developments in modern technology gave criminals a decisive edge over their law-abiding adversaries. Thanks to the V8 engine, bank robbers were able to quickly escape crime scenes. Using Tommy guns, the criminals had vastly greater firepower than the ill-equipped county sheriffs. Worse still, there was a lack of collaboration among America’s law enforcement agencies. Because of this decentralized approach, many criminals were able to evade justice by fleeing to nearby counties or across state lines. This made them effectively immune from prosecution or detection. Local sheriffs rarely made requests to extradite criminals from other localities. The existing Bureau of Investigation was corrupt and ineffectual. In 1924, President Coolidge vowed to clean up the Justice Department. Under the new Attorney General Harlan Stone, comprehensive reforms were implemented. The man tasked with the job was J. Edgar Hoover. In order to stop the violent criminals, Hoover transformed the Bureau of Investigation into a modern crimefighting force. He began to train his agents in the use of Tommy guns. He introduced the use of centralized fingerprints and files. From 1933 to 1934, America’s law enforcement and policing underwent a rapid modernization. Before this point, the FBI lacked any powers of arrest. To apprehend a criminal, they had to ask a local sheriff to act on their behalf. Bureau agents did not yet have the right to carry a gun. It was an incredibly inefficient and dangerous way of policing. Finally, after one too many deaths of law enforcement, Hoover and his federal Bureau began to implement some much-needed reforms. Over a pivotal period of about 18 to 24 months were the infamous crimes of Dillinger, Bonnie and Clyde, Pretty Boy Floyd, and other notorious offenders. Almost overnight, America’s law enforcement apparatus was modernized.

Arrest

At the beginning of 1934, Dillinger began to rampage through Chicago. During a bank robbery, he murdered a police detective. He and his wife Billie Frechette fled via Route 66 through Saint Louis to Tucson, Arizona. There, members of his gang were recognized and arrested by local police. Ironically, Hoover’s Bureau had nothing to do with this big-name arrest. Dillinger was extradited to Indiana to stand trial for murdering a police detective. Once Dillinger returned to Indiana in early 1934, he was jailed at Crown Point. When he was taken from the airport to jail, mobs of onlookers crowded around the criminal mastermind. To the astonishment of the press, Dillinger appeared to be a very friendly and straightforward person. He did not seem threatening. Dillinger exploited the widespread hatred of banks, which transformed him into a national figure. He became an almost Robin Hood-like character, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor.

Law and order

Hoover was especially outraged at the prevalence of bank robberies in America. It was an easy way for criminals to get quick access to cash. Gangsters in Chicago were not only successful at their deeds, but also very popular. Figures like Machine Gun Kelly and Pretty Boy Floyd became folk heroes. Hoover hated the way that gangsters were becoming seen as heroes for young people to emulate. So he embarked on a campaign to completely eradicate the menace of gangsterism from America. He devoted the Bureau’s resources to this one mission. Those efforts coincided in a massive media campaign, which generated publicity and visibility for the FBI. For Hoover, the War on Crime was more than just a literal battle. It was a clash of ideas, values, and imagery. With help from agent Melvin “Little Mel” Purvis, Hoover orchestrated a public relations campaign that presented the FBI as the valiant heroes fighting against dangerous criminals. Agents presented themselves as honorable and trustworthy men, who would be worthy of dating one’s daughter. Many of the Bureau’s agents came from a similar background as Hoover. They were well-educated and energetic young men. Most of them were white. The FBI presented its agents as working tirelessly to confront criminals. “The G-Men. This is a Bureau of scientific crime detection. New, modern, up to the minute. In action day and night. The FBI never sleeps,” said one of the Bureau’s public relations videos. This image of the G-men served as a counter-point to the gangsters. FBI agents were presented as more romantic and successful than their criminal adversaries. The reality was a little less glamorous. Many of the Bureau’s agents were inexperienced. Regardless, Hoover’s modern Bureau was a tour de force. One by one, high-profile gangsters were hunted down and brought to justice. Purvis led successful manhunts against Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, and Pretty Boy Floyd. Initially, much of the American public regarded the FBI with suspicion and distrust. But thanks to Hoover’s masterful propaganda campaign, the FBI gained the reputation as a reputable and efficient modern crimefighting agency. FBI agents began to show up in movies. This public relations campaign had a decisive effect on American life, paving the way for law-and-order politics.

Escape from jail

In March of 1934, Dillinger made yet another daring escape from prison. He stole the sheriff’s car, and drove across Indiana’s state laws. This was regarded as a violation of federal law, which allowed the FBI to intervene. Four days after his escape, Dillinger resumed his bank robberies. Popular folklore and legends began to surround this larger-than-life gangster personality. Hoover tasked Melvin Purvis with capturing Dillinger, but it was easier said than done. Whenever Purvis needed wiretaps, he was required to call a lawyer in Washington for directions. His information was often faulty. He had very few informants on the streets of Chicago. For a month, the Bureau searched in vain for Dillinger. But FBI agents managed to find him by accident. Dillinger had moved to Saint Paul in Minneapolis, a haven for bank robbers. There, he formed a second Dillinger Gang with a man named Baby Face Nelson. Nelson was nothing short of a psychopath, giving a crazed crackle as he fired his Tommy gun through the streets. Whereas Dillinger was careful not to murder innocents, Babyface had zero regard for human life. While in Saint Paul, Dillinger and his criminal wife aroused the suspicions of the landlady, who reported them to the local FBI office. At first, her warnings were ignored, but the clever woman was adamant. So the FBI office reluctantly sent two young agents to knock on the door. The wife offered a short distraction, allowing Dillinger to open fire with his Tommy gun. A gunfight erupted between FBI agents and Dillinger’s gang. Dillinger managed to escape, but was wounded in the leg. At this point, the bank robber reached the apogee of his infamy. But this publicity went hand-in-hand with that of Purvis. The sharp-dressed Purvis had an ego of his own, and he loved talking to the press. Despite his hunger for attention, Purvis did not have the skills to match. He raided the wrong apartments, and repeatedly allowed Dillinger to slip away. But the worst would come at Little Bohemia.

Little Bohemia

It was April 22, 1934. After a series of bank robberies, Dillinger and Babyface wanted a weekend away from the action. So they gathered at a small inn far northern Wisconsin, called Little Bohemia. The gangsters took it over for the weekend. But because their faces were so widely spread on the newspapers, the owner instantly recognized them as criminals. Dillinger assured the owner that he had no intentions of harming him, but the innkeeper was far from convinced. He called the FBI in Chicago for help. Melvin Purvis organized an expeditionary team, and went to Little Bohemia. On a cold Sunday afternoon, two dozen FBI agents descended on Little Bohemia by car and plane from Chicago and Saint Paul. The agents were fairly confident that they had Dillinger and Nelson surrounded. At this point, FBI agents had only been carrying guns for six to nine months. They hardly knew how to use the guns, let alone firing them at a criminal. Despite the lack of experience, they were taking on the nation’s most notorious criminal. Immediately, dogs started barking at the agents. Right away, this alerted Dillinger. When three drunk men got in their car to leave the inn, the FBI agents ordered them to stop. But the men did not hear the warnings. The agents unleashed gunfire, killing one and injuring two others. This misidentification allowed Dillinger and Babyface to escape through the back of the inn. About a mile away, Nelson stumbled upon a house, where the FBI agents happened to be at the time. Immediately, the gangster opened fire on the agents. He hijacked their car and escaped. The incident became a national embarrassment for Purvis and the FBI. The Bureau, which was still young at the time, began to be regarded as incompetent amateurs. Even worse, Purvis failed to maintain proper surveillance of Babyface’s wife. So an irate Hoover replaced him with a desk man named Samuel Cowley.

Public enemy

Having evaded the FBI at Little Bohemia, Dillinger became a popular sensation for the national and international press. The media began to look for other bank robbers. One of them was Bonnie and Clyde. Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were a criminal couple from Dallas. They tended to rob small-time drug stores, filling stations, and an occasional bank. As luck would have it, they were killed in May of 1934 by a gang in northwestern Louisiana. This happened at the height of public interest in Dillinger-esque bank robbers. Hoover and the FBI exploited the opportunity to valorize the victory. The Director and his G-men filmed themselves recreating the shootout that killed Bonnie and Clyde. Dillinger was clearly the most preeminent of these public enemies. But his infamy fostered the public’s interest in similar criminals, among them being Bonnie and Clyde, Pretty Boy Floyd, Babyface Nelson, and Machine Gun Kelly. In the spring of 1934, Dillinger’s wife was finally arrested by Purvis. Dillinger was present at the scene, but went undetected by the inexperienced Purvis. Dillinger was deeply grief-stricken by his wife’s arrest. He established a new hideout with a female pimp named Ana Sage. For years, she had run a whorehouse in northern Indiana. Ana was an immigrant from Romania, who was about to be deported. She approached the FBI, and offered to cut a deal. She would inform on Dillinger’s whereabouts, in exchange for not being deported. She, along with a runaway named Polly Hamilton, planned to meet Dillinger at a movie the next night. The next day, the FBI gathered in Chicago to hear from Ana Sage. She planned to meet Dillinger at the Biograph Theater. After the movie, the FBI agents successfully ambushed Dillinger, shooting him dead. With Dillinger gone, the Gangster Era had finally come to an end. Born from its ashes was a newly modernized FBI which, under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover, had become America’s preeminent crimefighting agency.

Learn More