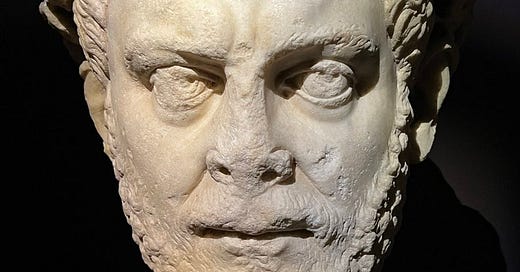

Diocletian: Crisis of the 3rd Century

How the Croatian-born ruler saved the Roman Empire for another 300 years.

It was the crisis of the 3rd century. No longer was Rome the world’s uncontested superpower. Generals and politicians alike vied unsuccessfully for Rome’s imperial throne. Barbarian invasions, civil wars, and peasant revolts all showed the empire was in decline. The economy was in free fall, and the currency had been debased beyond recognition. It was the end of an empire. There were over 20 emperors in 50 years. There was a brief period of stability under Emperor Aurelian in 270 AD, but he was assassinated. Then came Diocletian. He had new ideas about how to rule the empire.

Diocletian was born on December 22, 245 AD in the Roman province of Dalmatia, in modern-day Croatia. He came from humble origins. Most of his early life is unknown. His father was probably a scribe or a former slave. He married a woman named Prisca, and had a daughter with her named Velaria. Given his lack of political connections, Diocletian chose the path of the military. Around 282 AD, he became the head of the Imperial Cavalry, which protected the emperor himself. He was a skilled warrior and commander. When Rome’s emperor died while campaigning against the Persians, Diocletian was next in line for the imperial throne.

The Tetrarchy

Diocletian ruled the empire from 284 to 305 AD. He restored Rome to a position of strength. He was the first emperor in 50 years to survive for a significant time in office. His reign was remarkable, lasting about 20 years. Before him, the average reign was only one or two years, interrupted by constant civil wars. Diocletian’s reign marked a new phase of the Late Roman Empire, known as the Dominate (from the Latin dominus, meaning “lord”), which lasted well into the mid-7th century AD.

Diocletian helped to re-stabilize Rome’s economy and nobility. He was not from the normal senatorial ranks, but he did much to restore traditional Roman society. He came to power on November 20, 284. A lifelong military man, he enjoyed the support of the army.

He realized that the Roman Empire was simply too large to be administered by one man. So, for the first time, he had the empire split into west and east. He established a system known as the Tetrarchy, which divided power among four rulers. Each ruler was given a quadrant of the empire, and tasked with defending its borders.

He selected his trusted general Maximian as one of his junior emperors, called a Caesar. The other was Constantius Chlorus, the father of the famous Constantine. In 286 AD, Maximian was promoted to an even higher rank, called an Augustus, which was on par with Diocletian himself. Galerius was his Caesar in the east.

Diocletian turned Milan into the new administrative center of the empire. In the west, Maximian put down barbarian incursions by the Franks, Saxons, and Gauls. Diocletian fought off the invading Sarmatians in the east. In 296 AD, Persia declared war on Rome, and invaded the buffer state of Armenia. The Persians continued on into Syria. Over the next three years, the Romans struggled to blunt the Persian onslaught. Diocletian also dealt with a revolt in Egypt in 297 AD.

Reforms

During his reign, Diocletian implemented many different reforms. He made tax collection more efficient. The size of the army doubled, from 200,000 to 400,000. The Roman state began to supply its troops. This allowed the state to avoid dealing with Rome’s debased currency. More punishments were imposed for tax evasion, including collective penalties.

Under Diocletian, the imperial economy came under more centralized government control. He sought to re-stabilize the economy through wage and price controls in 301 AD. He passed edicts that forced people to remain in specific jobs. Free tenant farmers suffered greatly from those policies. Commerce and manufacturing were geared toward the needs of the empire’s defense. New taxes helped to strengthen Rome’s regime and army. His drastic economic reforms saved the empire from immediate collapse.

Diocletian connected the empire through a postal system. He reorganized provinces, distinguishing between civil and military ones. He imposed compulsory service on soldiers, bakers, the decurions of town councils, and tenant farmers. He also enforced Rome’s imperial religion.

Like other Roman emperors, Diocletian lavishly sponsored the construction of temples, marketplaces, baths, theaters, and stadiums, which were all used by the public. About 200,000 people regularly received free grain. Entertainment was provided on a grand scale. Public officials believed that, as long as the poor were fed and entertained, they would not revolt against the upper class. This was epitomized by the Roman satirical phrase “bread and circuses.” Stadiums such as the Colosseum and the Circus Maximus were used to host gladiator shows, horse and chariot races, and other forms of public spectacle.

Great Persecution

One of the chief concerns of Diocletian’s reign was the growing power of Christianity in the Roman Empire. None of his predecessors fully embraced the new religion, but tolerated it to varying degrees. Diocletian disliked Christianity, and he favored a return to Rome’s traditional paganism in order to save the empire. He created the Diocletian Baths to revive the old pagan rituals. He fixed temples, and built new ones. He meticulously observed the feast days of Roman paganism, and made sacrifices to the gods. He styled himself as, if not an actual god, at least a favored friend of the gods. As such, the emperor expected Rome’s citizens to offer sacrifices to him, but Christians refused. Christians were blamed for causing bad omens for the empire.

Beginning in the 4th century, he ramped up persecution of the Christians. On February 23, 303 AD, on the feast of the god Terminus, Diocletian officially outlawed Christianity. Churches were burned to the ground. Christians were arrested, and their property confiscated. Christians had no legal rights of redress, and were subject to tortures not inflicted on other Roman citizens. This became known as the Great Persecution, lasting from 303 to 311 AD. Other minority religions were persecuted as well, such as Manichaeism. Schismatic groups, such as the Donatists of North Africa, took a more hardline, dogmatic approach toward Christianity. Diocletian’s persecutions were not effective. Just six years later, his successor converted to Christianity.

Legacy

Diocletian did his best to save the decaying Roman Empire. After suffered a severe bout of illness in 304 AD, the exhausted emperor made an unprecedented step: he resigned. It was made official on May 1, 305 AD. His ingenious system of tetrarchy was ultimately unsuccessful, however, because the subsequent generation of Rome’s leaders were too power-hungry to share power. Still, he managed to preserve the remnants of Rome’s glorious civilization for at least another three centuries.