Did the Romans Have Orgies?

The truth is a little less sexy.

In the modern imagination, ancient Rome is often conceived as a lustful, hedonistic paradise of orgiastic, erotic pleasure. This happy, life-affirming pagan ethos is often contrasted with the morbid monkishness of Christian chastity and Victorian morality.

The truth about Antiquity, however, is a little less sexy. The Romans generally adopted a traditional view of marriage, and they imposed many taboos on sexuality. Marriage was generally between one man and one woman, two adults living together and sharing property for their common offspring. Most of these Roman restrictions on sexuality had to do with practical considerations, rather than any transgressions of the mind. It was vastly different from the Augustinian view, where lustful desire itself is deemed sinful.

The most striking difference between modern and ancient marriage, according to classicist Mary Beard, is the stark double standard for men and women. Despite its legal protections for women, Roman society was deeply patriarchal. This was long before feminism and women’s rights of any kind. Men were generally seen as having absolute authority over the family, and enjoyed more latitude to engage in extramarital dalliances. Female chastity, on the other hand, was strictly mandated. Only the highest-born women enjoyed rights of property ownership and voting—although, to be fair, most male Romans were also excluded from such political participation.

Unfamiliar and foreign as it may be, the ancient Roman perspective of marriage and sexuality can still provide guidance and inspiration for modern people. Today, the brothels at Pompeii are among Italy’s most popular attractions for modern-day tourists.

Marriage rules

To get married in Rome, all you had to do is declare your intention to marry. That’s it!

The Romans regarded marriage as a political tool, in order to cement ties between two noble families. It was not “marriage for love.” Marriages were generally arranged by the pater familias. The father had to give his approval to his kids’ marriages. Politicians got married and divorced based on their shifting political alignments. Children were married off for political reasons, sometimes as young as babies. To curb this, the Romans later passed a law that set a minimum age of 7 for marriage. The Romans allowed marriage of close family members, such as first cousins. From the early Empire onward, uncles could even marry their nieces.

Roman law did not recognize marriages to foreigners, slaves, or freedmen. Until fairly late in Roman history, at 217 AD, Roman soldiers were not allowed to marry at all. But it was still common for Roman troops to form long-term relationships with women, and for couples to live together in de facto common law marriages. Such informal unions caused resentment within the ranks of Rome’s military. Soldiers complained that their wives couldn’t inherit their property, and that their kids were considered illegitimate in the eyes of the Roman state.

Marriage was seen as a religious duty to produce children, to ensure that the family gods would continue to be worshipped. A bride-to-be typically dedicated her childhood toys to the household gods, signifying her transition from childhood to womanhood. As children, Roman girls wore ponytails. But on her wedding day, her hair would be coffered into a six-strand cone.

Monogamy?

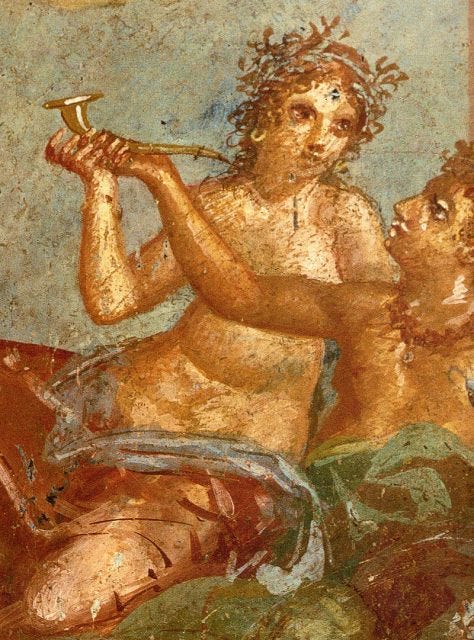

Nominally, a Roman marriage was expected to be monogamous. In practice, men were given more freedom within the marriage to enjoy extramarital affairs with other women, and sometimes even with other men. As long as those men were not freeborn Roman citizens, no one cared. It was actually expected. In the Roman view, men were seen as highly intimate beings that constantly needed to be satisfied. Soliciting escorts was not taboo, and many showed up in large numbers at parties and celebrations. Same-sex relations among men were not frowned upon. It was common for men, both bachelors and married alike, to engage in intercourse with all genders.

Female chastity

Although women did have affairs, it was not quite as socially acceptable to the Romans. Female chastity was highly valued, probably because of paternity concerns. The Vestal Virgins were Rome’s official female priesthood. Those virgins were selected from an early age out of noble families, and excepted to live a life of celibacy. They kept alive the flames of the Temple of Vesta. These women enjoyed special privileges not afforded to other Roman females, including the right to own property and to vote. Their chastity was so highly regarded, that anyone who broke the vow could be stoned or left to die.

The Roman family

The Romans understand a household as a basic unit of law and economics. A familia was a group of citizens, including their slaves, living under the same roof—usually a rural estate.

Richard Epstein, a law professor at New York University, explained the Roman concept of pater familias in a YouTube video for the Federalist Society. Rome was always a patrilineal system, meaning that a person’s family membership is recoded through the father’s lineage.

In individual households, the Roman male was expected to be the head of the home. Men were essentially mini-emperors, who distributed the rights and duties within the household. This was subject to his own discretion. Women were expected to obey and respect their husbands. Kids had to gain the father’s approval to enter business contracts.

The children (filii) of the family included all biological and adopted children of the household’s father. When the kids became adults, they could not acquire the rights of the father while he was still alive. Legally, any property acquired by individual family members belonged to the family’s estate, controlled solely by the father.

Over time, the absolute authority of the father became more moderate. The power over life and death was abolished. The right of punishment became more moderate. The sale of children became restricted to cases of extreme necessity. Under Emperor Hadrian, any father guilty of filicide was stripped of his citizenship, his estate, and permanently exiled.

Consent

The Romans didn’t have a modern concept of consent for sex. Rape was generally taboo, and the topic does appear in their mythology—notably the stories of Lucretia and the Sabine Women. However, they generally didn’t care much about age, especially for women. The legal age for girls to marry was just 12 years old, although lifespans were admittedly much shorter. For boys, it was 15, but it was not uncommon for men to wait until their mid-to-late 20s to get married. It was commonly held that a man was not mentally balanced until the age of 26. Girls were thought to be much more mature, and more prepared for the complexities of marriage.

Love or money?

In ancient Rome, marriages were arranged. This was long before the 19th century, which promoted the Romantic view of marrying for love. To the Romans, marriage was a political institution that solidified ties between powerful families. It was a way of maintaining and reinforcing social status, as well as mutual benefit for the respective families.

Ceremony

For most of the Republic, the most common form of marriage was the manus (“hand”) marriage. A manus marriage received its name from the fact that the woman was regarded as a piece of property that passed from the hand of her father to that of her husband. In this type of marriage, Roman women had no rights. Any property she owned was under her husband’s control. A woman was considered the legal equivalent of a daughter to her husband. The husband had all the powers of a pater familias, including over life and death. There were three ways that a manus marriage could be contracted:

1) Noble marriage

The first was the confarreatio, an elaborate marriage between patricians. Such marriages were celebrated by the sharing of cake and bread. This type of marriage reinforced the patriarchy of Rome’s society, as the bride was given by her father’s hand directly to the groom. Before the wedding, omens were read. The ceremony took place at the bride’s father’s house. The room would be decorated with flowers and tapestries. A priest and 10 witnesses would gather to officiate the event. The bride and groom would be joined together by a vow received by a matron. The ceremony usually took place just before sunrise, which symbolized the couple’s new life together. After the ceremony, the bride and groom would sit down while the priest made an offering to Jupiter. The two would then share spelt cake. After feasting with family and guests, a procession would take place into their new place of residence. As they walked, the bride would drop coins to honor the spirits of the roads, as well as her new husband. The husband would throw sweets into the crowd. Today, that tradition still exists as wedding guests who throw rice. Once the newlyweds reached their home, the groom would carry the bride over the threshold, and offer her water and fire as essential elements of their new home. The bride would then kindle her first fire, and then everyone feasted again until the night was over. It was an all-day celebration.

2) Purchased marriage

The second was the coemptio (“by purchase”). A bride could be literally sold off into marriage by her family. The groom symbolically gave money to the bride’ father. The husband essentially purchased the woman as a piece of property. It was more common among plebeians.

3) Marriage by cohabitation

The third type was usus, or a use-based marriage. It arose out of long-term cohabitation between partners. After leaving together for a year, the woman would be passed into the control of her husband in a manus marriage. This type of marriage was the most common among ordinary, poor Romans.

Loopholes in a usus marriage were sometimes exploited by fathers to maintain legal custody of their married daughters. This ensured that a daughter would not lose her dowry. It was known as a marriage sine manu (“without the hand”).

Although rare in the Republic, there was another type of usus marriage: the free marriage. In it, the woman retained all her own property and was free from her husband’s control. If the couple separated, the woman would keep all of her property.

The ring

To symbolize an engagement, a man placed an iron ring on the middle finger of the left hand of his wife. This is because, when Roman doctors did dissections of bodies, they believed there was a nerve which ran from the fingers to the heart. Wearing wedding rings is still practiced today.

Divorce

Divorce was common, and also totally accepted. There was no shame in divorce, and remarriage was often encouraged. Although this attitude gradually changed, couples were initially permitted to leave the union at anytime, as long as both parties consented. In practice, though, men were the ones who could unilaterally end the relationship. Once the divorce was decided, the woman would simply take back her dowry and leave her husband’s home. That would be the end of it.

Taboos

Romans were generally free to engage in sex. The only exception to this rule was a handful of taboos. One of them was incestum, or sex with a family member. The second taboo was raptus, or rape. For obvious reasons, it was forbidden to kidnap a woman for the purpose of having sex. However, this taboo applied even to women who went willingly, because they could not lawfully do so without their father’s consent. Women were still seen as men’s property. The third taboo was stuptrum, or misconduct. This included consensual affairs with one’s fellow freeborn Roman citizens. The fourth and final taboo was castitas, referring to women who chose a life of chastity, such as the Vestal Virgins. Such women were not allowed to back out of their vows. In most cases, breaking such a vow would result in the death penalty. Usually, the choice of chastity was made by the women’s families, when they were only about the age of 5 or 6. So those vows were hardly voluntary.

As strange and archaic as Roman norms may seem today, some of them are still practiced in various forms. Dowries still exist in many countries. In some places, minors are allowed to marry with parental consent, including several US states. There are still countries where girls are forced into marriages at the father’s insistence. Barbarism knows no age, but none can deny that the Romans contributed much to the progress of human civilization.