Crassus is one of the most significant figures of the Late Roman Republic. He was the very symbol of greed and decadence, as Rome’s civilization drew to an unfortunate and untimely twilight. Regardless, his life is of enormous interest and fascination to modern historians. Crassus’ larger-than-life personality bleeds right off the page. His inflated ego and avarice are too massive to force him into simplistic black-and-white characterizations.

A Rich Man is Born

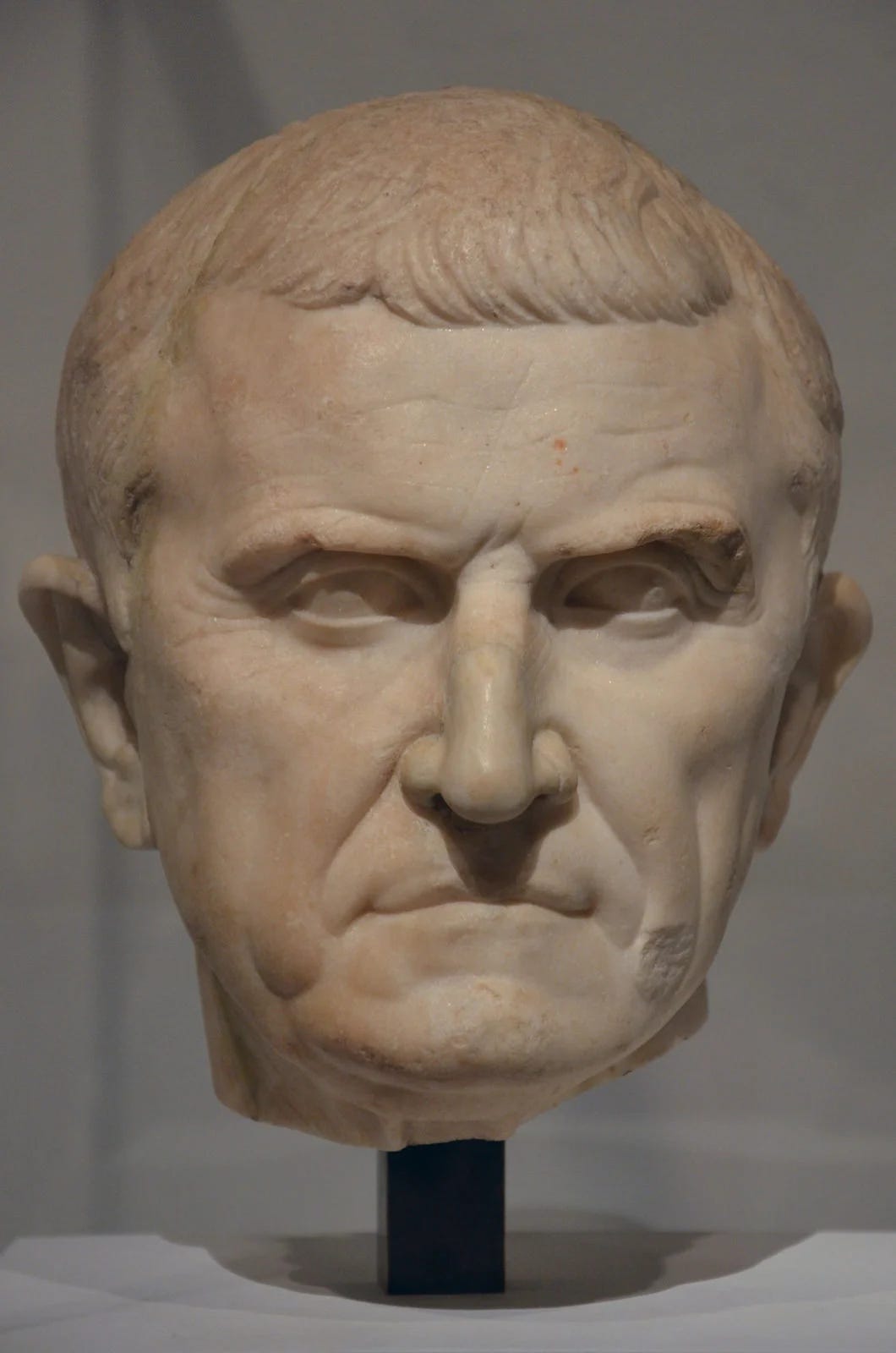

Plutarch gives the most detailed account of Crassus’ life in his Parallel Lives. Marcus Licinius Crassus was born in 115 BC to a prominent Roman family. He was the second of the three sons of Publius Licinius Crassus. His father was a successful man, serving as senator, consul, and a censor. Crassus’ father even had a Roman triumph held in his honor, a public ceremony reserved for only the most illustrious Romans. Upon the death of his parents, Crassus inherited a breath-taking fortune of 300 talents, or about $8.6 million in today’s money.

Sulla’s Civil Wars

Crassus came of age at a time when Rome was engulfed in a bloody civil war between two men, Sulla and Marius. In 88 BC, Sulla, who was consul, was preparing to march into the eastern kingdom of Pontus, ruled by King Mithridates VI. Marius coveted this job, and he pressured Sulla to relinquish command. Much to Marius’ surprise, however, general Sulla responded by marching on Rome. Sulla thus became the first figure in the Republic’s history to seize power by force.

Marius and his fleets managed to retreat to Africa. Back in Rome, Sulla consolidated his power. The Marians managed to seize back the government, purging Sulla’s supporters. Among them were some of Crassus’ relatives. Crassus fled Rome, and escaped to Hispania. For the next few years, he lived in a cave near the sea, where he privately amassed an army. In 84 BC, Cinna, Marius’ second-in-command, launched a surprise attack against Crassus by crossing the Adriatic Sea into Dalmatia. Cinna’s plan backfired, and he was executed by his own mutinous troops. Command of Marian forces was shifted to Marius the Younger, and then to a consul named Carbo.

In 73 BC, Sulla launched a second offensive against the city of Rome. This time, he was joined by Crassus and Pompey. Thanks to Crassus’ military leadership, Sulla’s faction won at the Battle of the Colline Gate in November of 82 BC. This allowed Sulla to declare himself dictator, and he spent the next couple of years hunting down any remaining Marius loyalists. Sulla was quite generous to his own cadre of supporters, Crassus highest among them.

Crassus benefited from Sulla’s political persecutions, enabling him to seize and confiscate the wealth of Marius supporters. “The many virtues of Crassus were obscured by his sole vice of avarice,” Plutarch writes. “And it is likely that the one vice which became stronger than all the others in him weakened the rest.”

The riches of Rome

Crassus earned his fortunes from a variety of sources. One of them was real estate, where he exploited the misfortunes of others to acquire their land. He also profited from slavery, silver mining, and acquiring agricultural land.

However, as Plutarch explains, Crassus was not necessarily an unpleasant character. In fact, he had all the genteel virtues of a traditional Roman aristocrat. The Greek historian described the Roman plutocrat as having “university kindness” and “dignity of person, persuasiveness of speech, and winning grace of feature.” In other words, Crassus was kind, generous, and handsome. He always opened his home to strangers. Unlike modern times, the ancient world had an ethic of hospitality, or xenia, which expected generosity to strangers.

Crassus, the politician

But wealth alone was not enough for the magnanimous Crassus. He was eager for social status. He pursued a career in politics, climbing up Rome’s traditional cursus honorum.

Plutarch writes that Crassus was a typical flip-flopping politician, who saw “very many changes in his political views, and was neither a steadfast friend nor an implacable enemy, but readily abandoned both his favors and his resentments at the dictates of his interests, so that, frequently, within a short space of time, the same men and the smash measures found in him both an advocate and an opponent.” For Crassus, personal benefit was more important than ideology.

There was one individual who sparked Crassus’ bitter envy: Pompey. Pompey was an esteemed military general who, unlike the real estate tycoon Crassus, was widely revered by the Roman public. When told of Pompey’s famous title “the great,” Crassus responded with mocking laughter, “How great?” But secretly, Crassus coveted his own string of military successes.

Killing Spartacus

In 73 BC, Crassus saw an opportunity to gain some military prestige. He was tasked with crushing a slave revolt in Rome, led by the famous gladiator Spartacus. Spartacus and his fellow slaves escaped from a gladiator school in Capua, and led raids against the Italian countryside. Such revolts were common in the ancient world. In fact, Spartacus’ uprising is known as the Third Servile War, because there were at least two such revolts before it. At first, the Roman Senate cared little about the minor revolt. They summoned only small militias and local patrols to hunt down the rebel slaves. None of them could subdue the wrath of Spartacus, who bested his Roman rivals. Spartacus’ numbers continued to swell, as more and more runaways slaves joined their ranks. Even professional legions of Roman soldiers, led by the consuls themselves, were unable to pacify Spartacus’ rebellion. The Senate began to panic. Enter Crassus. A desperate Roman Senate appealed to the rich man to crush Spartacus’ movement. Crassus was promoted to the rank of praetor, and received command of a staggering eight legions.

Crushing the revolt had an adverse effect on Crassus’ moral character. He became increasingly ruthless and brutal. It was a trait that he never displayed before, but which were brought to the surface by the circumstances. One of Crassus’ subordinate commanders, a man named Mummius, defied orders. Mummius was instructed not to engage the slaves in battle, but the overconfident general did so anyway. It resulted in defeat. An incensed Crassus responded by reviving the practice of decimation, where he would have every tenth soldier executed. Crassus inflicted this punishment on an army of 500 men.

Despite the early losses, Crassus managed to recuperate. He trapped Spartacus at Bruttium, and waged a war of attrition. Pompey, who had been busy in Spain, soon arrived with reinforcements. Crassus confronted Spartacus at the decisive Battle of the Silarus River. Despite suffering many losses, the Romans managed to prevail against their slave opponents. Spartacus was killed in battle, along with tens of thousands of his soldiers. Thousands more were imprisoned and later crucified along the Appian Way, on Crassus’ orders. A contingent of 5,000 slaves managed to escape alive from Silarus, but they were mauled down by Pompey’s army. Much to Crassus’ frustration, it was Pompey who received credit for the victory in the eyes of the Senate.

Caesar’s alliance

Crassus returned home to Rome, where he was elected as co-consul with Pompey in 70 BC. However, their joint consulship was fraught with division and tension. Nothing got accomplished.

This changed with the arrival of Julius Caesar, who was able to cement an alliance between the two men. Caesar was a prominent Roman citizen who was climbing the ranks, and he saw the potential of allying with Pompey and Crassus. At first, Pompey was the leader of the alliance. He was Rome’s most celebrated and revered commander. Crassus too was more powerful than Julius; he was the city’s most influential landowner. Both Pompey and Crassus were more powerful than Caesar.

Caesar didn’t want to alienate either of them, so he urged them to forge an alliance against the Senate. Prominent senators, such as Cicero and Cato, were unified in their opposition to all of these military strongmen. So Crassus and his two cronies formed their own counter-alliance, known as the First Triumvirate, around 60 BC.

In the words of Livy, the Triumvirate was a conspiracy of three citizens against the entire Roman society. They did not share an agenda, and their alliance was based solely on pragmatic self-interest. All of them agreed on the need to bypass the Senate and establish autocratic control of the Late Republic. Of the three men, Crassus was the moderate who mediated between Caesar and Pompey. Pompey was a traditionalist, while Caesar was a revolutionary. Crassus held the alliance together by constantly taking the middle ground.

Caesar was the biggest beneficiary of the Triumvirate. With support from the two others, he was elected consul. Caesar gained command of an army, which he used to conquer the Gauls. After a few years of military glory, Caesar began to be detested by his two allies. Despite heavy resistance from the Senate, Pompey and Crassus became co-consuls of Rome in 56 BC. They were assigned governorships of Rome’s overseas provinces. Pompey received two provinces in Hispania, while Crassus inherited Syria. Although the circumstances of this move are not entirely clear to modern scholars, it was a brilliantly orchestrated move by Pompey and Crassus to counter Caesar’s growing influence.

Crassus, the corrupt man that he was, used his governorship to enrich himself. He exerted financial leverage of the Senate through a sordid assortment of bribes, loans, and dishonest business practices. Nothing could satisfy his rapacious desire for wealth. The greedy Crassus expanded his conquests beyond Syria, and prepared to war war against the neighboring Parthian Empire. Parthia was Rome’s chief enemy for the better part of half a millennium. In the mid-3rd century BC, the Iranian Parthians annexed the Greek Seleucid Empire, and rampaged through the Middle East. Parthia expanded westward until it reached Roman territory. The two sides, Rome and Parthia, had previously co-existed for 200 years thanks to the buffer state of Armenia.

This changed in 54 BC, when Crassus was looking for another opportunity for military conquest. It is unclear why the 60-year-old Crassus would embark on such a difficult, frivolous mission. He had been out of action for 20 years, since the time of Spartacus. Was it his greed? Perhaps his envy of Pompey and Caesar? No one really knows.

Crassus’ ambitions went far beyond Parthia. He sought to expand into the Far East, as far as India and Baktria. Thanks to his massive fortunes, Crassus was able to levy his own army for the campaign. In 54 BC, without the Senate’s approval, the ravenous Crassus began his campaign into Mesopotamia. Most cities offered tribute to the Romans, and were their allies. This was especially true of the Greek cities, which had been founded by the Macedonians under Alexander’s reign.

The self-assured Roman general made a number of devastating mistakes, which destroyed his campaign. He refused to invade through Armenia, despite having permission to do so from the kingdom’s leadership. Instead, he invaded through the Euphrates River. Crassus allied with the wrong people, and he ended up suffering a massive defeat at the Battle of Carrhae, one of the worst in Rome’s military history. Despite having numerical superiority, the Romans were slaughtered by the Parthians. Even Crassus himself was killed. According to Cassius Dio, the defeated Crassus was forced to swallow molten gold as a punishment for his greed. By the end of his life, Crassus’ net worth was 7,100 talents, which is about $200 million in today’s money. Some scholars have estimated his wealth in the billions. Whatever the exact amount, he was undoubtably Rome’s richest man.

Legacy

Crassus’ untimely death was a turning point in Rome’s history. It resulted in the collapse of the First Triumvirate, as Caesar and Pompey began to fight each other. It marked the beginning of 250 years of conflict between Rome and Parthia. Last but not least, the Roman Republic was nearing its end. In the historiography of ancient republican writers, people like Crassus represented how affluence led to the decadence and decline of the Romans. To them, Crassus was the very definition and symbol of greed, which hallows out a republic in favor of riches and conquest. But to modern eyes, perhaps he represents something else. The hubristic tragedy of Crassus represents a warning against the convulsive social effects of economic inequality, as well as the folly of vainglorious military adventurism.