One of the most enduring concepts bequeathed to us by ancient Rome is the idea of citizenship. Perfected over centuries, Rome’s unique constitutional system reached its complete form by the end of the 4th century BC. Many of our modern ideas about the rights and duties of citizenship, voting, elections, etc. owe their debt to the glories of the ancient Roman Republic.

What is citizenship?

A citizen, to the ancient Romans, was a special legal status that afforded certain rights and privileges. Citizens were always a small minority of the total populace. Even at the height of the Roman Empire, around the 2nd century AD, only 6 million of the empire’s 50 million members were actually citizens. The requirements for citizenship were being a free adult male, and passing the census. By definition, women, children, and slaves were excluded from full citizenship. The census was given to test a person’s age, geographical origin, family, wealth, and moral virtue. For centuries, the Romans were reluctant to extend citizenship, even to the thoroughly Romanized peoples of Italy. But they were forced to do so by the Social War (91-88 BC) of the Late Republic. Even after Rome acquired overseas provinces, the Romans still didn’t want to extend citizenship to the provinces on a large scale. Clearly, it meant a LOT to the Romans!

Symbols

The most visible symbol of citizenship was the classic white toga. This garment originated with the ancient Etruscans. By law, only the citizens of Rome could wear it.

Duties and rights

In the Early and Middle Republics, the two main duties of a citizen was to fight in the army, and to cast votes in elections. Citizens enjoyed equal protection under the law, at least on paper. One of the rights of citizenship was that you could not be punished without a trial. Trials were required to be held in the city of Rome itself. When Christians were persecuted in the empire, the law required that those who were Roman citizens receive their trial in Rome itself. But if not, the local magistrates could deal with it. One of the most potent phrases of Ancient Rome was civis Romanus sum (“I am a Roman citizen”). The phrase instantly granted its speaker certain rights. Cicero recounted one instance where a corrupt governor had a Roman citizen was beaten and tortured. From Cicero’s eloquent recounting, it is vividly clear just how egregious a violation it was for the Roman government to punish one of its own citizens. Citizenship was highly, highly valued. Unlike today, it was not just about which passport you have, or what flag you wave on holidays.

Class conflict

Long before Marx, there was already an idea of class conflict within Ancient Rome. It is called the Struggle of the Orders. It was fought between the rich land-owning patrician class, against the lower commoners, known as plebeians. The struggle lasted from the 6th century BC until 287 BC. The patricians were the most prominent aristocratic families of ancient Rome. Over time, their dominance became institutionalized through laws. This meant that only patricians were allowed to hold high public office. By law, patricians were only allowed to marry their fellow patricians. The vast majority of Roman people were plebeians. Their inferior status led to the eruptive outbreak of social unrest. Because of the conflict, the privileges of the patricians were gradually eliminated over time. However, the patricians did maintain a certain prestige all throughout Rome’s history. It was not until 445 BC that plebeians and patricians were legally allowed to intermarry. Roman citizens were divided up according to their wealth. The Roman government regularly appointed a special magistrate, called a censor, who reviewed the wealth and moral virtue of all Rome’s citizens. If you were rich enough, you could rise up to the status of equestrian (from the Latin eques, meaning “knight”). Knights wore specialized togas with a purple stripe, as well as a gold ring. Their status was instantly recognizable on the streets of Rome. Their togas and rings were the ancient equivalent of a Ferrari. Many knights owned large commercial enterprises. Over time, these wealthy upper-class people gained special privileges in government.

Rome’s constitution

In the analysis of the Greek historian Polybius, ancient Rome derived its power from its unique organization—which he called its constitution. Polybius and other ancient writers admired Rome’s political institutions, because they evolved and perfected over many centuries. Many of these institutions persisted even after the Republic became an Empire. Collectively, Rome’s political offices were known as the cursus honorum (“course of honor”). Rome was ruled by elected political officials, called magistrates. There were minimum age requirements. There were term limits. These offices were collegial, meaning that many people held them at the same time. All of these rules existed to prevent the centralization of power.

Quaestor

The lowest office was called a quaestor. The minimum age was 30. They were involved in financial affairs. Originally, there were only two such officials, but that number eventually ballooned into 20. They were given specific duties regarding taxes and government finances.

Aedile

The next level was the aedile. The minimum age was 36. They were involved in urban affairs. Four officials were elected each year. They oversaw the maintenance and repair of urban infrastructure. They regulated markets to ensure fair trade, and to standardize units of measurement. They also staged public festivals.

Praetor

Above them was the praetor. The minimum age was 39, and they served in judicial functions. The number of praetors grew from one to eight, over the course of the Republic’s life. They were tasked with overseeing courts and legal proceedings.

Consul

The most prestigious post of them all was the consul. With a minimum age of 42, they were the chief executives of Rome. For most of the Republic’s history, consuls likewise served as the generals of armies. Consuls were so important, that their reigns were used to date events.

Lictors

Roman officials had special aides, called lictors, who enforced their orders and cleared the streets for them. As a symbol of Roman power, each lictor carried a fasces, an ax surrounded by a bundle of rods tied together with a purple ribbon. The fasces represented the power of magistrates to enact violence on behalf of the state, as represented by the ax and the beating rods. Furthermore, it is the origin of the word fascism.

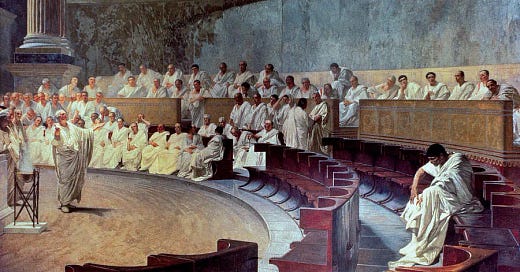

Senate

Finally, there was the Roman Senate. The word senate comes from the Latin senex, meaning “old man.” During Rome’s monarchy, the Senate was an advisory council to the king. They were composed of elderly aristocrats. In the Republic, by contrast, the Senate became one of Rome’s most powerful political institutions. Senators wore togas with a thick purple stripe, which proclaimed their high status. At any given time, there were about 300-500 senators. The only way to become a senator was to first hold a lower public office. Membership was for life. On paper, the Senate’s law-making powers were limited. Its main function was to advise. But in practice, the Senate’s recommendations were effectively the law. Over time, the Senate gained a number of formal powers, particularly regarding foreign policy.

Dignitas

Rome was a deeply competitive society, where male members were expected to vie for prestige and status, which was denoted by the Latin word dignitas. It was something like a celebrity index, in modern terms. To the Romans, a person’s influence and reputation were of the highest importance. To gain dignitas, a person could be elected to office, win on the battlefield, engage in public works, obtain wealth, successfully prosecute a legal case, deliver a good speech, enter into a prestigious marriage, or give generous food denotations to the poor. Sometimes, even negative publicity, such as a sex scandal, could bolster one’s social status in Rome. Dignitas was fleeting, and always had to be renewed. It was also a zero-sum game, because only a few people could enjoy major attention at any given time. It was public, and competitive. It was the most important thing for a Roman aristocrat. The need for dignitas among Rome’s politicians and generals was one of the driving forces behind Roman imperialism.

Tribune of the Plebs

There was one office that was not part of the traditional cursus honorum. This was the Tribune of the Plebs. Their primary duty was to protect and secure the interest of the plebeians. The office was added to diffuse the tensions between the patricians and plebeians. It may have been caused by a mass labor strike. Like the other magistrates, tribunes were elected and served one term in office. They had special powers. They could directly propose legislation to the assemblies. He enjoyed special legal immunity. The most important power was the veto, which enabled the tribune to invalidate laws, revoke actions by other officials, and overturn legal decisions. The powerful privilege was rarely used, but its existence sought to curb the excesses of Rome’s aristocracy.

Patronage

In addition to its formal offices, Rome was run by an unspoken patronage system, which linked together individuals of different classes. It was designed to reduce tensions between patricians, plebeians, freedmen, slaves, citizens, and non-citizens. In this system, powerful men served as patrons to their social inferiors, called clients. Patrons offered financial and legal protection for their clients. They offered free cash and food in times of need. They leveraged their influence to get jobs for their clients, or get them out of legal troubles. Clients received material aid from the patrons. Patrons would receive favors from the clients. They were expected to vote for their patrons. They were expected to attend and applaud the speeches of their patrons. In a ritual known as the salutatio, the poorest clients would greet their patrons in the morning, and perhaps receive food or money. Roman aristocrats gained prestige from the crowd size of their clients. Clients paraded around their patrons at the Forum.

Voting assemblies

Rome was divided up into three voting assemblies, which elected different officials. Elections were held at the Campus Martius. Originally, votes were simply shouted out, but voter intimidation forced the Romans to resort to secret ballots, which were cast into urns. 500 officials perused the area to prevent cheating. The first assembly was the comitia centuriata. They elected consuls, praetors, and censors. They presided over treason trials. Before the Punic Wars, they voted for most legislation. The elective districts were organized into seven classes, based on a person’s wealth, as determined by the census. It is superficially similar to America’s Electoral College. Elections were not really democratic; they were more oligarchic, weighted heavily in favor of the richest citizens. The second assembly was comitia tribuna. Citizens were divided up by geography, into 35 tribes. They elected aediles and quaestors. They voted on most legislation. Winners were based on majorities. It appears democratic, but it was skewed toward the rich, although in more subtle ways. Elections had to be held in Rome, which was dominated by the rich. There were no absentee ballots. Everyone voted in one place. This required time and money. The third assembly was the Concilia Plebs. It was organized like the second assembly, but it excluded patricians. They elected tribunes.