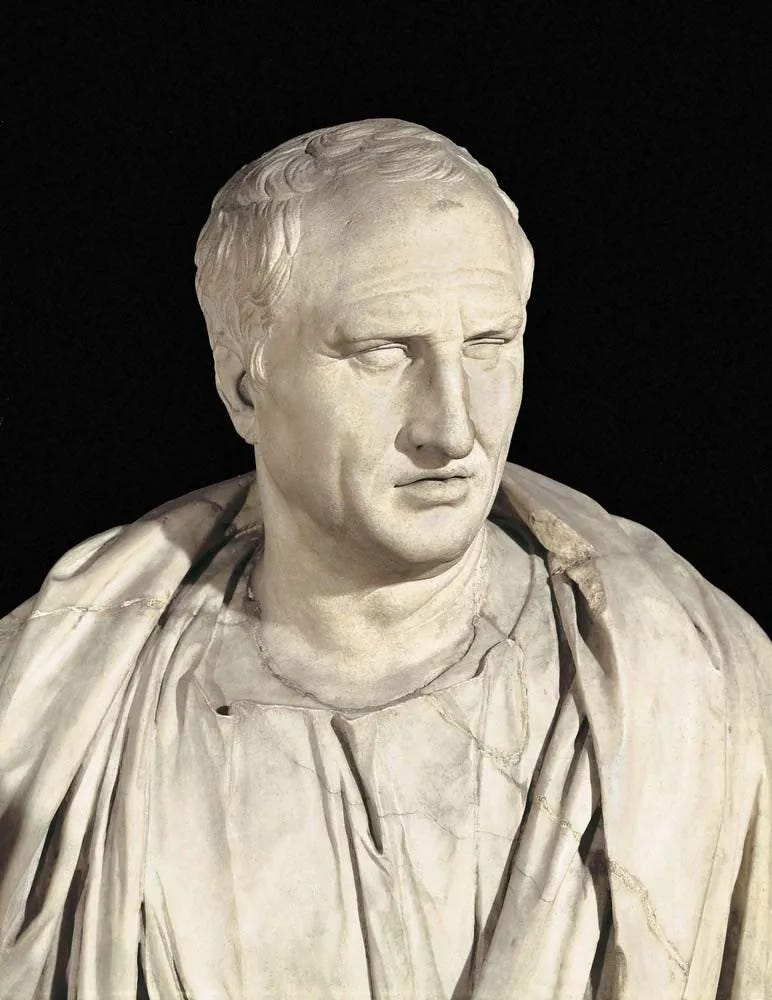

Cicero: The Republican of Rome

How one brave man challenged Caesar's dictatorship and forever shaped Western civilization.

“Let the welfare of the people be the ultimate law” (De Legibus, III, 3).

Cicero is easily one of Western civilization’s most outstanding figures. He was praised by Thomas Jefferson as “the father of eloquence and philosophy.” His very name is a stand-in for masterful oratory, republican virtue, and philosophical excellence.

The larger-than-life personality of Cicero is bequeathed to modern readers through his large corpus of surviving works. His treatises were so esteemed that, after the Gutenberg Bible, they were some of the first documents in human history to be mass-printed.

The Roman Republic

Central to understanding Cicero is a firm appreciation of the glories of ancient Roman civilization. According to Roman tradition, the Eternal City was founded by two brothers, Romulus and Remus, who were raised by a she-wolf. This myth is found in Livy’s History of Rome. Another founding myth claims that Rome was founded by the Trojan hero Aeneas, the son of the goddess Aphrodite and the namesake of Virgil’s epic poem The Aeneid.

Key to Rome’s geopolitical dominance was the superiority and strength of its impressive professionalized military. Roman legions were highly trained and impeccably organized. They were famous in the ancient world for their unsurpassed victories on the battlefield. Legions engaged in aggressive but successful campaigns of expansion under the auspices of Rome’s Senate, and later by Rome’s emperors. The legions of Rome conquered vast territories of what would become Europe. It was one of the largest civilizations in human history.

Despite the vastness of their territory, the Romans maintained a common identity through their unique culture, institutions, and language. Romanitas, as it was called (literally “Romanness”) diffused across the Mediterranean, which the Romans affectionally called mare nostrum (“our sea”).

Unlike their Jewish and Christian counterparts, the pagan Romans were never disrupted by pointless wars of religion. They easily integrated conquered peoples through their practice of religious syncretism. When Rome subjugated Greece, it adopted the myths of the Homeric gods. Zeus became Jupiter. Aphrodite became Venus.

Anomalous among many ancient societies, the Romans pioneered a unique system of political representation, called republicanism. The word “republic” itself comes from the Latin res publica, and Cicero himself was one of the chief exponents of this noble ideology.

In ancient Rome, ordinary people exercised sovereignty through a representative body, known as the Senate. Cicero was a novus homo (“new man”), meaning that he was the first in his family to serve in the prestigious Roman Senate. He was later elected as consul, Rome’s highest political office. Unlike many Romans, Cicero was a self-made man. He was a striking example of meritocracy in a world that was filled with decadence, nepotism, and corruption.

Cataline’s conspiracy

Cicero first made his reputation as a lawyer. His persuasive speeches became defining classics of the Latin language. His literary forms were voracious copied by others. It is something of a miracle that Cicero’s writings have survived at all, given the ferocity of his political enemies. Many of his writings were carefully preserved by the medieval Catholic Church, which regarded the Latin orator as a virtuous pagan.

One of Cicero’s early enemies was a man named Cataline. Cataline came from an entrenched Roman family. He was accused of various crimes, including adultery with a Vestal Virgin. Cicero claimed that Cataline was only spared the death penalty because he bribed the judges at his trial. Cataline lost his bid for the consulship against Cicero, partly because his idea of debt forgiveness was unpopular with Rome’s elites. This prompted Cataline to conspire against Rome’s Republic and overthrow its government.

The plot was unmasked by Cicero, who gave a series of famous speeches against Cataline before the Roman Senate. One of the most famous lines is “Oh the times! Oh the morals!” With this line, Cicero bemoaned the moral degradation of the Late Republic’s ruling class. Cicero successfully mobilized the Senate’s opposition to Cataline, who was forced to flee Rome; he died shortly after in battle. Cicero had Cataline declared an enemy of the state, although it was not technically a legal declaration. Ironically, Cicero’s questionable decree led to his own banishment from Rome. Even Caesar thought banishment was a sufficient punishment for Cataline, but Cicero was an uncompromising hardliner.

Fighting Caesarism

Julius Caesar became one of the Late Republic’s most prominent politicians. The Roman dictator offered to incorporate Cicero into the First Triumvirate, but the senator refused. Cicero saw Caesar as an existential threat to the Republic, and he judged accurately. For his opposition to the Triumvirate, Cicero was exiled from Rome, but he was brought back and pardoned by Caesar.

Although Caesar did not participate in Caesar’s assassination, he was clearly not in favor of the dictator. He was a staunch defender of Rome’s constitution against the unlawful, dictatorial powers of Caesar, who had recently declared himself dictator for life.

In the aftermath of Caesar’s assassination, Mark Antony became consul of Rome. He clashed with Cicero and the Senate, who accused him of dismantling Rome’s constitution. In another set of famous speeches, known as the Philippics, Cicero denounced Antony as a tyrant. The Roman senator pledged his support behind Octavian, Julius Caesar’s adopted nephew and Antony’s chief rival.

Unfortunately, Cicero had made yet another political miscalculation. Octavian was just like Caesar, and he formed a second Triumvirate, this time with Mark Antony and Lepidus. The new alliance ruled Rome with an iron fist, punishing all dissenters with death. Cicero was among those proscribed by the regime. Antony summoned a group of hand-picked assassins to kill Cicero, who had fled Rome. The soldiers found Cicero at his seaside villa, where the Roman orator was beheaded. His decapitated head and hands were brought to Rome, where they were displayed as macabre trophies in the Senate. Antony’s wife, Fulvia, took a further step by pulling out Cicero’s tongue and sticking pins in it, in a final act of revenge.

Legacy

The glorious Cicero is remembered today not only for his golden-mouthed speeches, his supernal eloquence and literary chops, but also for his character and values. He was one of the West’s earliest and most influential spokesman of natural law theory, and he boldly fought on behalf of Rome’s political institutions.

Today, the Latin orator has much to teach us. He was a deep, thoughtful man and a first-rate philosopher. He asked the big questions. He contemplated the nature of God, morality, justice, politics, government, virtue, and the afterlife. All of life’s most pressing existential questions have already been treated by our beloved Cicero, whose insights should be read and understood by all serious students of history.