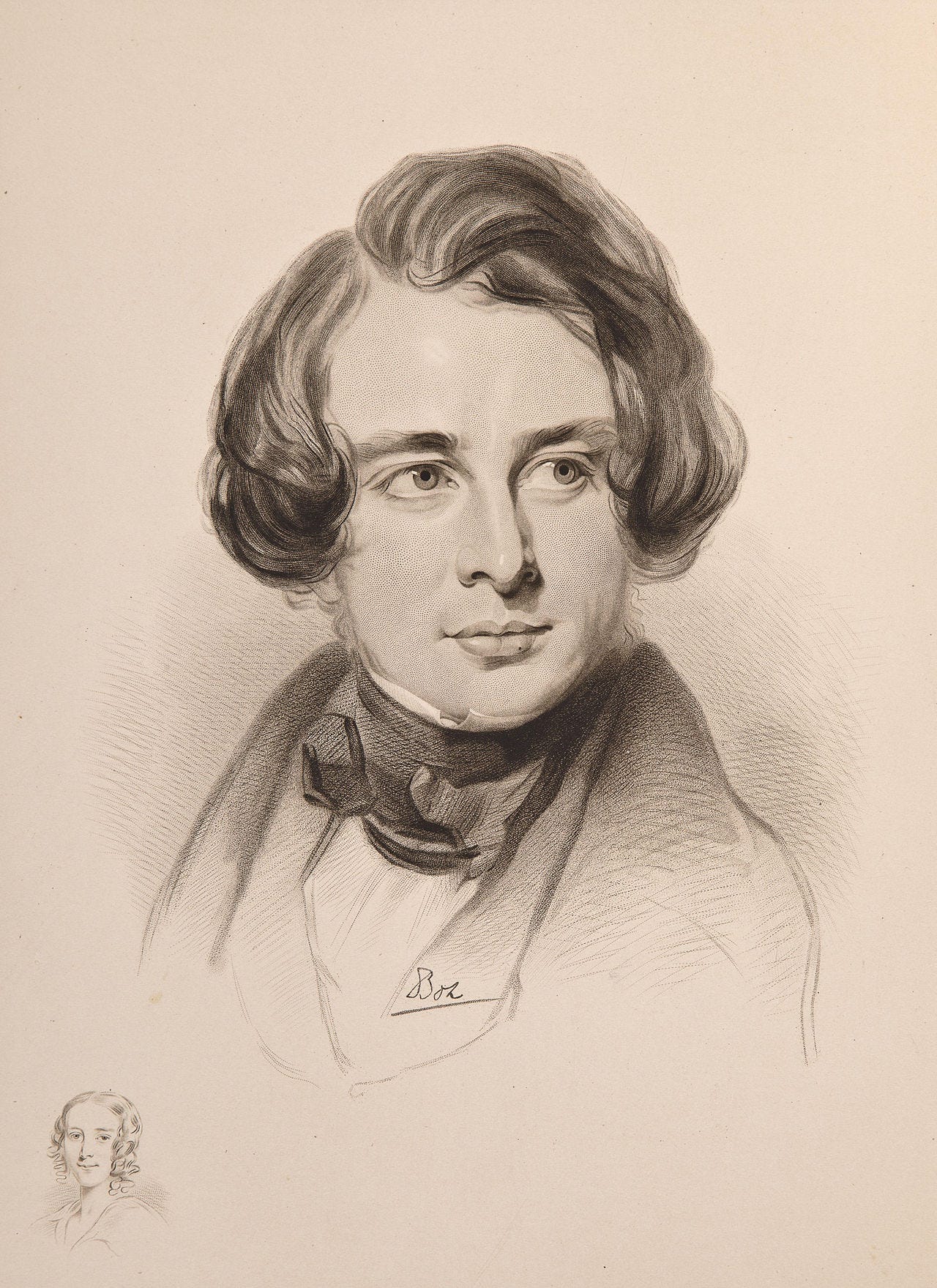

Charles Dickens: The English Novelist

The literary genius behind Christmas Carol, Oliver Twist, and much more.

Dickens came of age during a tumultuous time in English history. The Napoleonic Wars had just come to an end. The rosy optimism of the Victorian Era was just on the horizon. England underwent a massive social transformation, thanks to the explosive growth of the middle class. Dickens was one of those families. Not everyone benefited equally from the Industrial Revolution. Industrial workers lived lives of destitution and hard labor. This social inequality of the working class would later motivate Dickens’ famous novels. As a child, Dickens was quite unremarkable. He showed no early signs of genius. His father served in the British Navy. Young Charles spent his formative years in the cosmopolitan atmosphere of Chatham. He would later look on his childhood with an almost Edenic nostalgia, as a time when he lived in a stable loving family.

Factory years

In 1822, John Dickens, Charles’ father, was transferred to London at a reduced salary. As the debts grew worse, Charles was forced to pull out of school. Years later, he would draw inspiration from his father to create the character of Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield. When Charles was age 12, his father was thrown into the Marshalsea prison for debt. As the eldest male son, Charles was not allowed to move into the prison with the rest of his family. He was instead sent to work in a shoe polish factory. The experience crushed his spirits. He suddenly found himself in the company of uneducated working boys, in a dull and repetitive manual job. The factory years were incredibly hard on young Dickens. It instilled him a feeling of guilt, shame, and incompetence. After about a year, John Dickens managed to scrape together enough money to get out of debtors prison. But his mother still wanted Charles to work, due to financial needs. It left him with deep psychological unease. “Words cannot express the secret agony of my soul,” Dickens later recalled in 1846. “I never afterwards forgot. I never shall forget. I never can forget.”

Law clerk

However, Charles’ fears went unrealized. He was never sent back to the factory. Instead, the 16-year-old began his first career as a clerk in a lawyer’s office. He spent a couple years there, but did not like it. He only enjoyed himself in acts of petty mischief. He found law to be boring. Lawyers are ruthlessly mocked in his novels. As a young clerk, Charles spent his monotonous days copying legal documents. At night, he frequented the theater, and he considered becoming an actor. Instead, he became a stenographer for Parliament. Soon enough, he turned his journalistic attention toward political elections. Traveling by horseback or stagecoach, he attended political rallies across the country. Charles was enormously successful at the job.

First love

In 1830, Dickens met his first serious love, a woman named Maria Beadnell. She would later inspire his character Dara from David Copperfield. The man was smitten with passion. “She was more than human to me,” he confessed in David Copperfield. “She was a fairy, a sylph. I didn’t know what she was. Anything that no one ever saw, and everything that everybody ever wanted. I was swallowed up in an abyss of love in an instant.” The daughter of a London banker, Maria became the obsessive object of Charles’ infatuation. He regularly wrote poems and letters to her. The passion spilled off each page. “I have never loved, and I never can love, any human creature living but yourself,” he wrote to her in 1833. Like many Victorian women, she played with his amorous affections. But Charles was too poor, and he was rebuffed by her family. Dickens was devastated. He fell into a melancholic depression. Nevertheless, Dickens got back into his writing. He began penning short descriptions of London’s daily life, which he submitted for publication. His submissions were frequently found in newspapers, which were always in need of filler content. Working with an artist named George Cruikshank, he collected his writings and published them as an illustrated book. Sold under a pseudonym, it sold well enough to convince Dickens to become a writer. Dickens began to socialize in literary circles. He met a young woman named Catherine Hogarth, the daughter of a well-respected journalist. After a long and tender courtship, Dickens married the girl in 1836. He wanted to build a home to compensate for his own tarnished family. After Catherine got pregnant, her sister Mary moved in with the couple.

Amazing author

Soon enough, Dickens’ literary career began to prosper. He was approached by the publishers Chapman and Hall with an offer. It would become the Pickwick Papers. The concept originated with a small-time comic artist named Robert Seymour. He brought a series of sketches to a publisher about cockney sportsmen. Cockney sportsmen were urban people who clumsily tried to imitate the rural gentry. The publisher decided to hire out an inexpensive writer to produce the idea. They approached Dickens, who eagerly seized the opportunity. When Seymour committed suicide, it allowed Dickens to choose his own illustrator. He picked an artist named Hablot Knight Browne. Dickens redesigned the story, recasting it as a tale of innocence. It followed the adventures of four young bachelors. Genre-wise, it was a typical bourgeois erotic comedy. The Pickwick Papers proved to be enormously popular. It sold 40,000 copies a month, at a time when 300 or 400 sales was typical. Much of Dickens’ success came from the serialized format of his works. By selling his books in parts, it became affordable to the masses of English society. Sold for only a shilling, his books were cheap and popular. Thanks to word-of-mouth gossip, many readers were enticed to purchase the next installment. As Dickens’ writing career took off, he was able to afford his first home at 48 Doughty Street in London. There, he continued to pen his monthly installments of Pickwick. He also began working on two future novels, Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby. Days and evenings were filled with his writing. Sometimes, Dickens wrote from the comfort of his living room, because there was nowhere else to write. The rest of the family continued their ordinary affairs, even as Charles was writing with laser focus. Dickens was restless. He was always thinking about what to writ next. At times, he walked the streets of London for twenty miles in the middle of the night. When Dickens’ name first appeared in print in 1837, he instantly became a celebrity. Still in his twenties, Dickens had emerged as England’s youngest and most promising writer. His works were read by every strata of British society, from the royalty to the working class. But amidst his growing professional success, tragedy struck Dickens. His 17-year-old wife died suddenly of illness. It crushed Charles for the rest of his life. In 1843, Dickens published Martin Chuzzlewit, which mocked the amateurishness of Victorian nurses. The novel sold dismally, and his popularity dropped. To recover, Dickens looked to his Christmas tree for inspiration. What resulted was the famous Christmas Carol. Christmas was in the air in Victorian England. The first Christmas card was invented and sent. The new royal family, Victoria and Albert, popularized Christmas celebrations. The holiday was revived as a season of optimism, youth, and generosity. Dickens wanted his Christmas book to be full of decoration and style. His demands were so expansive, that it dramatically increased the production costs. This ate into his profits.

Crisis of the mind

After publishing Dombey and Son, Dickens transformed into an international phenomenon. He no longer had to worry about money. This prosperity allowed him to be more selective about his writing projects. His newfound affluence did not cut into his creativity. He embarked on his most ambitious project yet, called David Copperfield. It became his most autobiographical novel, but it was difficult for the author to confront his past. “The old, unhappy feeling pervaded my life,” he confessed candidly in the book. “It was as undefined as ever, and addressed me like a strain of sorrowful music faintly heard in the night. There was always something wanting.” By 1850, Dickens’ life was entirely different. He and his wife lived in a fine London house with their ten children. They lived along with Georgina Hogarth, who had replaced the deceased Mary as the household helper. But despite all of these blessings, none could assuage Dickens’ discontent. He grew disillusioned by his marriage and family life. He could not help but feel he was missing out on something. Suddenly, he found a letter from his first lover Maria, asking to see him. Charles was elated. But what he found was a fat, unattractive 40-year-old woman. He was shocked by what he saw. Three years later, she became the basis of the character Flora Finching in Little Dorrit. Still struggling with internal distress, Dickens returned to Chatham, where he purchased his childhood dream home. But he remained restless. He tried to alleviate himself by participating in social reform issues, editing several magazines, and writing theater productions. Dickens’ later works took on a profoundly darker tone unseen in his early writings. Starting with Bleak House, the Dickensian world became one of despondency and despair, mitigated only by a glimmering faith in human goodness. “I want to escape from myself,” Dickens wrote in 1856. “For when I do start up and stare myself seedily in the face, my blankness is inconceivable, indescribable, and my misery amazing.” For Dickens, the cause of his pain was an unhappy marriage. “I believe my marriage has been for years and years as miserable a one as ever made,” he complained bitterly. “I believe that no two people were ever created with such an impossibility of interest, confidence, sentiment, and tender union of any kind between them, as there is between my wife and me.” Like many men, he hated his wife. She was not particularly attractive or intelligent, even though she was nice. He found marriage to be a crushing constraint of his creativity. He fell in love with another woman named Ellen Ternan, a 19-year-old actress he had cast in his play The Frozen Deep. In 1858, Dickens legally separated from his wife Catherine. All but one of the children remained with their father. He all but excommunicated her from his life, and urged his children to stay away from their mother. Meanwhile, Dickens grew more fervent in his affair with Ellen. She presented a new kind of womanhood, one that was more assertive and independent. This was reflected in the strong female characters of Dickens’ later novels. But Dickens’ loneliness was too intense to bear, and his affair with Ellen did little to help.

End of an era

By the 1860s, Dickens had completed some of his greatest works. In A Tale of Two Cities, he told a tale of sacrifice, set in the French Revolution. The dark story of Great Expectations reflected the author’s own repressed passions and secrets. Despite his ailing health, he began to publicly read his most beloved books. His tricks of face and voice brought his characters to life. It earned him considerable amounts of money. By 1867, Dickens decided to embark on a second American reading tour. Although he earned a lot of money, it cost him dearly in terms of physical exhaustion. He returned home to London as a frail, spidery old man. Still, the powerful Victorian novelist was not done yet. He began plans for a new novel, which became The Mystery of Edwin Drood. It would be his last and unfinished novel, because he died of stroke before its completion. He also embarked on a final reading tour in Great Britain. He did so accompanied by a physician, who was sometimes unable to feel any pulse. He was unable to keep food down. Despite his feebleness, Dickens performed with an almost magical vivacity and energy. Dickens died as one of the world’s most beloved literary figures. He received an esteemed burial in the Poet’s Corner of Westminster Abbey.

Learn More