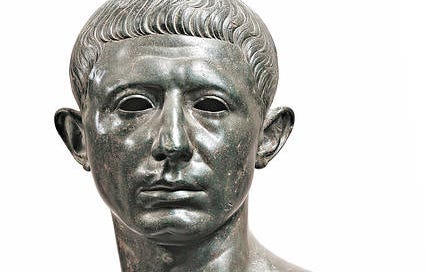

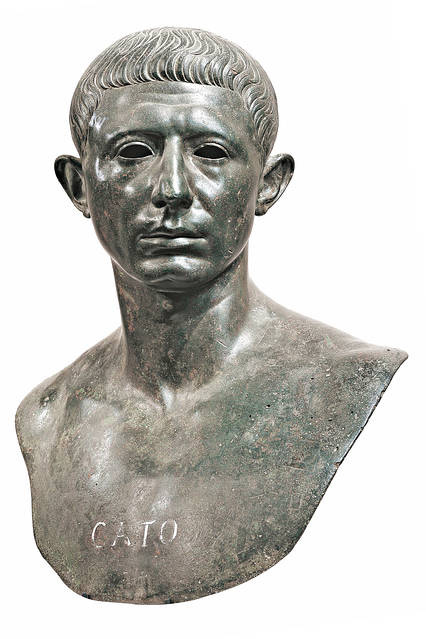

Cato and Caesar: A Roman Rivalry

The fascinating conflict between an ultraconservative Roman senator against the autocratic Caesar.

Cato is one of the most prominent figures of the Late Roman Republic. Famous for his conflict with Julius Caesar, Cato—both in modern times and even in his own day—was the living embodiment of the Roman Republic’s political and social traditions.

Early Life and Education

Cato was born in 95 BC. By the time of his birth, his powerful family had fallen out of prominence. Many of them were killed, and he was an orphan by the age of four, along with his sister Porcia. When his father ran for praetor, Cato and his sister lived with their mother Livia. He was especially close with his half-brother Caepio, and his half-sister Servilia. Servilia later went on to marry Brutus and became Caesar’s mistress.

Cato was a dull and slow-witted child. But he was also thoughtful and deliberate. Even from childhood, he was a deeply moralistic person. Through his life, Cato’s unwavering convictions made it difficult for him to understanding other people’s perspectives. When Cato turned 16, the precocious young man became a priest. This powerful religious role introduced him to the world of Roman politics.

Cato received a typical aristocratic education. He was a student of philosophy, notably Epicureanism and Aristotelianism. He is widely recognized as one of the leading thinkers of Roman Stoicism. He was a powerful oratory who adopted war-like language. He used archaic language that resembled Rome’s republican past.

Cato walked the streets of Rome in his famous toga, without a tunic or sandals. His toga used much more purple than the standard crimson toga. He was an arch-conservative who embodied the very spirit of Rome’s ancestors, the mos maiorum. He did this deliberately, because he believed the Republic had lost its way, and wanted to restore Rome’s former glory.

Caesar and Cataline

Cato became prominent at a time when Rome was the Mediterraean’s uncontested superpower. Despite its vast territory, the Republic was imploding from the inside out. It was a time of upheaval and change. Because of the conquests, Rome’s ultra-conservative culture was being challenged and modified. Cato responded to this by presenting himself as the embodiment of classical Roman virtues, which made the Republic great.

Although there had long been conflict between plebeians and patricians, Rome saw the rise of political factions for the first time in its history. These were not necessarily political parties, in a modern sense. They didn’t have a headquarters or a shared platform. They were all led by members of the same rich, slave-owning elites, but they pandered to different constituencies.

Cato became the public face of the Optimates. The division between the Optimates and Populares began with the rise of a radical populist named Cataline, who called for debt forgiveness and terrorism against the Senate. Cataline was even willing to align with Rome’s foreign enemies to conspire against the Senate.

Cato became an icon of Stoicism, the model of a virtuous Roman citizen. There was a robust debate on what to do with Cataline and his co-conspirators. Should they be executed summarily, because of national security reasons? Caesar persuaded the Senate that the Roman way of life demands the conspirators receive a trial. But Cato managed to persuade the Senate in his favor. In one of his most iconic speeches, Cato lambasted the Late Republic for its moral decline, and demanded immediate execution of the traitors. An angry Caesar, having lost the debates, stormed out of the Senate. He tried to disrupt the Senate’s proceedings, but was unsuccessful. Born was a lifelong enmity between Cato and Caesar. Even the historian Sallust, who was a partisan for Caesar, admired Cato for his uncompromising principles.

A Corrupt Alliance

Cato was the most vocal opponent of Caesar, Crassus, and Pompey, whose alliance was based solely on their shared hatred of the Roman senator. He masterfully used political persuasion to stymie the corrupt ambitions of the Triumvirate.

As tensions grew between Caesar and Pompey, Cato urged the latter not to negotiate with the renegade conqueror. Because Pompey adopted a hardline stance against Caesar, Caesar decided to march across the Rubicon into Rome itself. When Pompey’s forces were bested by Caesar at the fateful Battle of Pharsalus, Pompey fled to Africa. Cato was left alone, without any key allies, to resist Caesar’s advance. Caesar offered to pardon Cato, but the senator refused. To Cato, Caesar was nothing more than a thuggish tyrant who lacked any legitimacy. Cato read from Plato’s Phaedro, before committing suicide as an act of protest against Caesar.

Cato’s Legacy

The bitter rivalry between Caesar and Cato was rooted in deep personal animosity. The senator may have been jealous of the general. Caesar was a very intelligent and gifted orator, who enjoyed massive popularity among the ordinary citizens of Rome. Cato’s own popularity was restricted to the elitist Senate. Cato clashed fiercely with the Triumvirate, and refused to play along with their corrosive influence over Rome’s representative institutions.

For centuries after Cato’s death, the esteemed Roman senator has been recognized as a martyr for the cause of republicanism. He defended the Republic and its institutions, notably the Senate, against the centralized oligarchy of Caesar and his cronies.