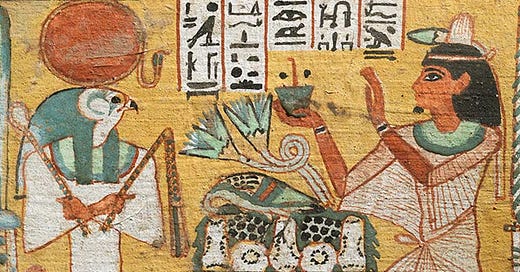

Pyramids, mummies, chariots, weird-looking animal gods. Everyone knows ancient Egypt. This glorious civilization is one of the oldest in human history. One could devote an entire lifetime studying the enthralling mysteries behind the world of the Egyptians.

Here is a brief overview of ancient Egypt, for beginners.

Overview

The Egyptians grew out of the Nile Valley. Our timeline begins with pre-history, around 3100 BC. This was when Upper and Lower Egypt were unified under King Narmer.

Egyptian history is categorized according to periods of political stability, which are interspersed with times of revolution and chaos. The stable periods are the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom. This corresponds with the stages of the Bronze Age.

Egypt reached its apogee during the so-called New Kingdom. From their capital at Nubia, the Egyptians ruled over a sizable portion of the Levant. After this point, their civilization began a period of slow decline. Egypt was then invaded by rival foreign powers, including the Hyksos, the Nubians, Assyria, Persia, and Alexander the Great’s Macedon.

After Alexander’s conquest of Egypt, the Greeks founded the Kingdom of Ptolemy. It ruled over Egypt until the year 30 BC, when Cleopatra gave it over to the Romans.

Prehistory

In the Predynastic and Dynastic periods, Egypt’s climate was much less arid. The iconic scenes of dry desert did not apply then. Large regions were covered with luscious trees and grazing animals. Birds drank from the rivers of the life-giving Nile.

The Egyptians were hunters, and they domesticated many animals fro the first time in human history.

By around 5500 BC, various Egyptian factions began to settle down into agricultural settlements. They relied on livestock for their sustenance. Combs, bracelets, pottery, and beads were produced.

Around the 4th or 3rd millennium BC, Egypt fell under the rule of the Sumerians and Akkadians of Mesopotamia.

Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom of Egypt lasted from 2686 to 2181 BC. Major advances were made in agriculture, which allowed for better farming, population growth, and the emergence of stable political administration.

Grand architecture appeared, such as the famous Giza pyramids and the Great Sphinx. Led by viziers, Egypt’s government officials collected taxes. They organized irrigation projects, which improved the crop yield. They drafted peasants for ambitious construction projects. The Egyptians also insisted a system of justice, which maintained law and order.

As administration became centralized in Egypt, a new class of educated elites emerged. Scribes and other royal officials received vast estates from the King in exchange for services. Pharaohs gave out land grants to local temples and cults, which reinforced monarchical power.

After 500 years of royalism, Egypt’s economy could no longer endure the lavish ostentation of a centralized regime. The power of pharaohs was curtailed and challenged by regional governors, called nomarchs.

From 2200 to 2150 BC, Egypt began to suffer from droughts and political instability. This started what is called the First Intermediate Period. The central government collapsed.

Local leaders, now free from the financial burden of a monarchy, were able to create thriving cultures in Egypt’s provinces. All social classes benefited. Creativity and art flourished. Literature was expressive, optimistic, and breathtakingly original.

As local rulers began competing for power, a new centralized regime slowly spanned out from the city of Thebes. Under the new regime, Egypt entered a cultural and economic renaissance known as the Middle Kingdom.

Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom lasted from 2134 to 1690 BC. Egypt recovered from its woes, and resumed its art, literature, and construction projects.

The capital was moved from Thebes to Itjawy. The Kings of the 12th Dynasty redistributed land and conquered new territory. Rich gold mines fell into their grasp. A Wall of the Ruler was built along the Eastern Delta of the Nile to defend against foreign invasion.

The last of the great rulers, Amenemhat III, allowed for the Semitic-speaking Canaanites from the Near East to settle in the Delta region. These people provided a cheap source of physical labor, especially for Egypt’s mining and construction industries.

The Nile’s flooding strained the economy, and sparked yet another time of chaos. During the Second Intermediate Period, the Canaanites gained prominence in the Delta, and set up a new regime. They began to be known as the Hyksos, which translates to “foreign rulers.” They assimilated into Egyptian culture, and introduced new tools of warfare—including the composite bow and the now iconic horse chariot. Under the new regime, Egypt began to pursue territorial ambitions in the Near East.

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom lasted from 1549 to 1060 BC. These rulers oversaw a period of unprecedented prosperity by securing their borders and strengthening diplomatic ties with their neighbors. These included the mighty empires of Assyria, Canaan, and the Mitanni. Egypt reached its territorial zenith. The pharaohs embarked on a colossal construction campaign to promote the cult of the god Amun, based in Karnak.

Around 1350 BC, Akhenaten instituted his radical religious reforms. He revived the obscure deity Aten as the new Supreme Being of the Egyptian pantheon, and suppressed the worship of other deities. He moved the capital to the new city of Akhetaten, in modern-day Amarna. He introduced a new religious and artistic style. After his death, Egypt’s traditional religious order was restored, and Akhenaten’s legacy was branded as heresy.

Around 1279 BC, Ramesses II acceded the throne of Egypt. He built more temples, statues, and obelisks. He fathered more kids than any pharaoh in history. A fierce military conqueror, he defeated the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh, in modern-day Syria. The two sides agreed to history’s first-ever peace treaty around 1258 BC.

Because of Egypt’s opulence, it became a tempting target for ambitious invaders, notably the Berbers of Libya to the west. An ambiguous collection of pirates known solely as the Sea Peoples invaded out of the Aegean. Egypt was able to repel the invasions, but lost its sovereignty over southern Canaan to the mighty Assyrians. The growing external threats were made worse by domestic turmoil, including corruption, civil strife, and tomb raiders. The high priests of Amun, based in Thebes, accumulated vast estates of land and riches, splintering the kingdom during a Third Intermediate Period. This was when Assyria conquered Egypt, sometime between 671 and 667 BC.

The Assyrians controlled Egypt through a vassal system. These rulers became known as the Saite Kings. The Assyrians themselves were kicked out of Egypt by the powerful Persians. The Egyptians briefly regained their independence in the 4th century BC, but were eventually conquered yet again, this time by Alexander the Great.

Greek Conquest

In 332, Alexander the Great conquered the Persian province of Egypt. The Egyptians greeted the Macedonian as a great liberator. Alexander and his generals established a regime there, known as the Kingdom of Ptolemy. A new capital was set up at Alexandria. This Hellenistic paradise became a center of refined culture and learning, as well as the home to the legendary Library of Alexandria. It was also home to the Lighthouse, which lit the way for ships, thus helping trade. The manufacture of papyrus became a leading industry for Egypt under the Ptolemaic Greek rulers.

Although Egypt was Hellenized, it retained much of its own native culture. The enlightened Greek rulers took great pains to respect the time-honored traditions of the Egyptian populace. This was done to ensure loyalty and respect. They built new temples in traditional Egyptian style, and sponsored traditional cults. Greek rulers styled themselves as pharaohs. Classical Greek sculpture absorbed Egyptian influence. The pantheons of Greece and Egypt were harmonized and syncretized. Despite the Greeks’ efforts to be benign occupiers, native Egyptians led a revolt after the death of Ptolemy IV.

Roman Egypt

Meanwhile, the Romans began to rely heavily on Egypt’s grain supply, and so they got deeply invested in Egypt’s political situation. This prompted the Romans to intervene, annexing Egypt as a province of their own empire. Cleopatra and her Roman lover, Mark Antony, were both defeated at the hands of Octavian at the Battle of Actium around 30 BC.

Now in control, the Romans imposed law and order. They enforced tax collection, and cracked down on piracy. Alexandria grew increasingly important for Mediterranean trade. To the Roman mind, the Egyptian capital became associated with the exotic luxuries of the Orient. Egyptian goods were in high demand.

Beginning in the mid-1st century AD, Christianity began to take hold of Egypt. The Romans dismissed it as just another Oriental cult. But they underestimated the religion of the Nazarene. The Christian faith was fanatically uncompromising in its evangelical efforts to win over new converts. It threatened Egyptian and Greco-Roman pagan customs.

The Romans, worried by the growing threat of Christianity, began to crack down on it. Persecutions intensified, culminating with that of Diocletian around 303 AD. Slowly but surely, Christianity infected and hollowed out the dying Roman Empire. After three centuries, the tables were turned against the enlightened pagans. In 391, Christian Emperor Theodosius banned pagan rites and shut down temples. Christians engaged in mob violence against pagan temples and art.

Egypt’s native culture fell into a death spiral. Although ordinary people continued to speak their language, the Egyptians eventually lost their ability to read hieroglyphs. Temple priests and priestesses evaporated from Egypt’s public life. Temples were converted into churches, or sometimes abandoned altogether.

The Roman Empire was split up in the 4th century, and Egypt became part of the eastern half. The capital was held at Constantinople. In the twilight years of the Empire, Egypt was conquered by the Sassanian Persians in the 7th century AD. It was briefly recaptured by Eastern Roman Emperor Heraclitus, before falling to the Muslim Rashidun caliphate by the mid-century.