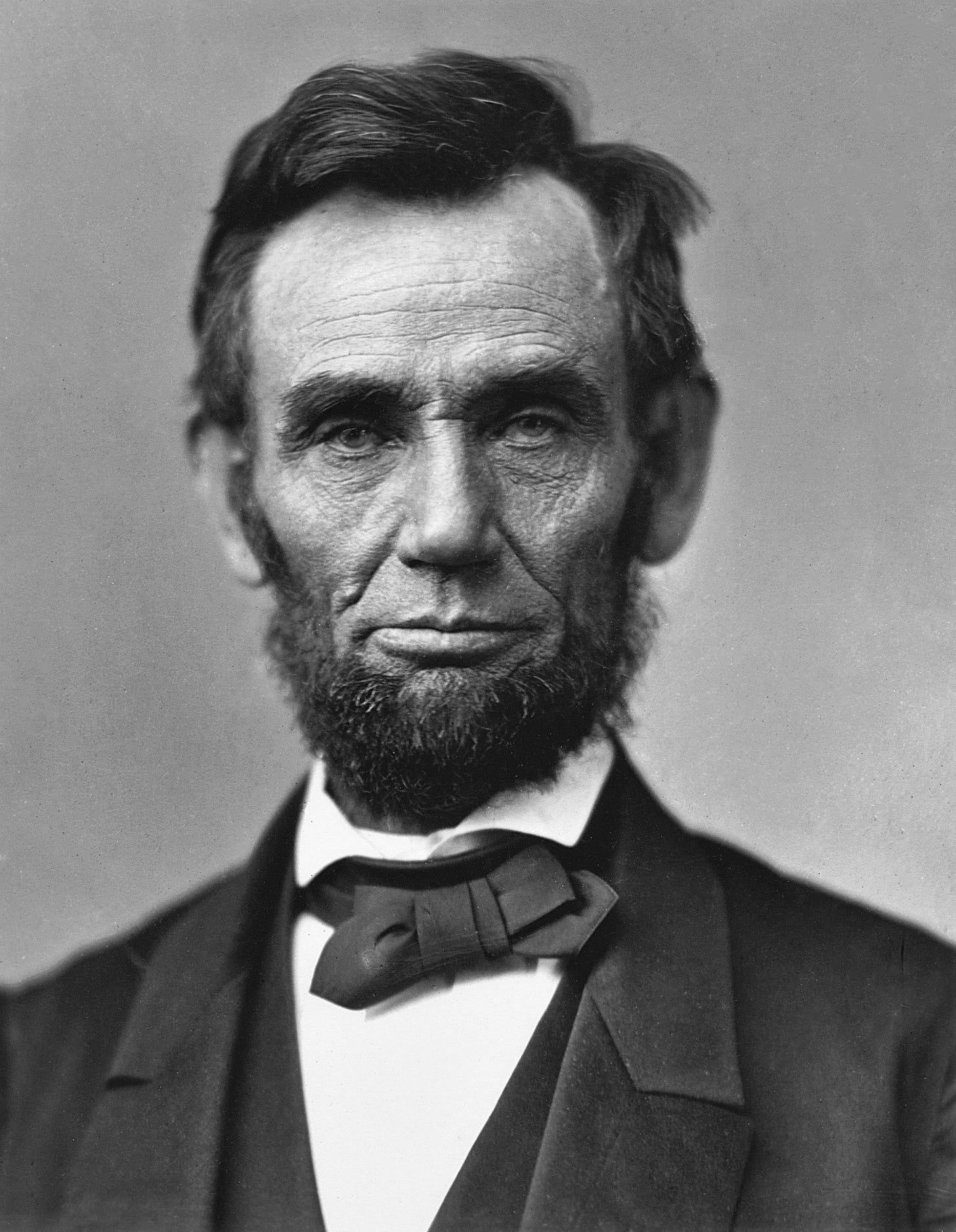

Abraham Lincoln: The Great Emancipator

How one of America's greatest presidents saved the Union and freed the slaves.

If there was ever a single man who embodied the very spirit of the United States, it would have to be the great Abraham Lincoln. Through his masterful Ciceronian rhetoric, Lincoln awakened the conscience of a nation. He united a country, and brought victory in an unprecedented crusade for human freedom. None worked more diligently to eradicate that vile institution of human bondage, which plagued the first century of American history.

Here is the story behind one of America’s greatest political and moral leaders, the magnanimous Abraham Lincoln.

Kentucky farm life

Lincoln was born in the frontier woods of Kentucky. His grandfather came from Virginia in the 1780s, and had been killed by Indians. His son, Thomas Lincoln, raised crops and started his own family. Thomas and his wife Nancy had a son, who was named in honor of the grandfather. His name was Abraham Lincoln.

Abe was born in a small login cabin on February 12, 1809. He spent his childhood in various cabins, as Thomas moved from Kentucky to Indiana in search of better land. From Abraham and his sister Sarah, life was a harsh sentence of manual labor. It was a life that young Abe was desperate to escape. Because of this poverty, he possessed an ambition to obtain a better life. He sought an education, which would allow him to transcend the drudgery of this existence.

Lincoln’s parents

Even worse, Abe hated the way his father treated him. Thomas Lincoln, although not necessarily abusive, used to resort to corporal punishment against young Abe, even for trivial offenses. Abe was treated like a slave himself, and because of this, he came to abhor the vile institution. He was able to identify with the enslaved Africans in the United States.

Lincoln found consolation from the maternal love of his mother Nancy. When he was age 8, she died from drinking infected milk. Later on, Lincoln recalled his mother’s death as the bitterest agony of his entire life. His father, who needed help to raise the two kids, married Sarah Bush Johnston. She had three children of her own, meaning that the crowded cabin of the Lincoln family held seven people. Abe developed a fond relationship with his stepmother, and she even preferred him to her own biological children.

Lincoln’s stepmother encouraged the young boy’s passion for learning. He taught himself how to read and write by the age of 7, using a turkey feather pen and blackberry ink. But Lincoln barely saw the inside of a schoolroom, because his father kept him busy on the farm. Abraham Lincoln had less than a single year’s worth of formal education, but he worked vigorously to educate himself. He walked miles to find and read books. He cared not just about information, but also about forming his own independent thoughts and opinions. Lincoln hated his father. He saw him as lazy, lacking ambition, and anti-intellectual. But by law, Abe had to work for his father until age 21. The second he turned this age, he left the family farm.

New Salem

In 1831, the runaway Lincoln landed in a commercial village in Illinois, called New Salem. It was his first taste of urban life. With a population of 100 people, it had a dynamic intellectual culture. Lincoln got work as a clerk in a general store. He instantly gained popularity because of his honesty, as well as his inexhaustible collection of humorous anecdotes.

Everywhere he spoke, Lincoln captured the attention of the people around him. Whether it was around potbelly stoves at the store, in storefronts, or at courthouses, the effervescent Lincoln was always collecting and telling stories. Lincoln’s great storytelling helped to mask his insecurity about his poor and uneducated origins.

He was something of a loner. He often brooded, and suffered from what he called melancholy. At times, this moodiness verged on clinical depression. He tried to fight back these sad feelings by cultivating his characteristic sense of humor.

Black Hawk War

In 1832, the Indians under Chief Black Hawk waged a war to reclaim their ancestral homelands.

Abraham was one among many American men who eagerly volunteered to put down the rebellion. He was elected as the captain of his local militia. Later in life, he described this as his most enjoyable achievement. It was an enormous ego boost for Lincoln, who often felt ashamed his background. It also gave the future president the first taste of being elected for public office. He didn’t run for the role; he was chosen for it. And, one could say, he was born for such leadership roles.

Entry into politics

When the Black Hawk War ended after a few months, Lincoln set his sights on achieving political office. The 23-year-old ran for state legislature. Just a year before, Lincoln had been, in his own words, “friendless, uneducated, and penniless.” But now, he saw his destiny in the vibrant bustle of American electoral politics.

Lincoln’s bid for office failed, but he tried again two years later. This time, he found success, because of his masterful people’s skills. He had a radiant quality of a wise old man, despite being in his 20s. People trusted him, because he gave off the aura of a wise old sage, or a benevolent grandfather.

Because the state legislature was a part-time job, with part-time pay, Lincoln worked several other jobs. He worked as a surveyor of land. He served as postmaster. He even started his own store, but it went bankrupt. Even amid all those activities, he still found time to teach himself law. Within three years, he managed to earn his law license.

Most of state politics were at the local level. But Lincoln did take a prominent stance on one national issue: slavery. Slavery had existed in America for 200 years, but the persistence of this pestilent institution was quarantined to the rural South. Abolitionists in the North campaigned for its total termination. However, most Northerners were racists who cared little about the happiness of black people.

In Illinois, the legislature condemned the abolitionists as troublemakers. Lincoln criticized this motion, and he denounced slavery as a grave injustice. It was a gutsy move, and was at least partially motivated by his own personal ambition. However, despite his vocal opposition to slavery, Lincoln was forced to admit that the Constitution allowed it. Like many of his Northerner counterparts, he saw no legal way to eradicate slavery.

Springfield

In 1837, Lincoln left New Salem to practice law at Illinois’ capital of Springfield. He rode into town on a borrowed horse, with barely enough money for a place to stay. A store owner named Joshua Speed, who admired one of Lincoln’s speeches, offered a share of his room above the store. He became Lincoln’s closest friend.

Springfield was a dusty frontier town. Hogs freely roamed the streets. Despite this, it was still the most sophisticated settlement Lincoln had seen up to that point. Having grown up in dirty frontier cabins, Lincoln knew little about the etiquette of Springfield’s polite society. He wore rough boots to social functions. He was especially awkward around women. “Springfield women avoid me,” he complained. Lincoln had a tall, spidery physique, standing at six foot four. His movements were clumsy and unattractive.

Lincoln’s women

Despite being one of America’s greatest presidents, the glorious Lincoln was not so successful when it came to women.

In New Salem, Lincoln experienced a budding romance with a beautiful young girl named Anne Routledge, the daughter of an innkeeper. He was heartbroken when she died unexpectedly of typhoid. Many years later, in the White House, the president would recall his love for her.

Lincoln’s next romance was with a woman named Mary Owens. She put on weight, causing Abraham to unfavorably compare the fatting woman to the obese Shakespeare character Falstaff. Mary was not satisfied either, complaining about Lincoln’s lack of affection. The relationship clearly wasn’t working, and their engagement ended in cancellation.

“I will never again think of marrying,” Lincoln said in 1837. “I could never be satisfied with anyone who would be blockhead enough to have me.”

Marriage to Mary Todd

But fate had other plans. Among Springfield’s high society, Lincoln caught the attention of an ambitious young woman named Mary Todd. She was one of the city’s most desirable socialites. The 21-year-old woman came from a rich Kentucky family. At the time, she lived in Springfield with her sister. Mary intended to marry a man who would become America’s president. Attracted by his ambition, she set her sights on Lincoln. Abraham met the girl, but didn’t know what to say. He stood there, mouth agape, unable to speak a word to the woman. His jaw hung open, as the experienced Mary chatted away about every subject possible. The refined Todd could speak about gossip, poetry, politics, Shakespeare, the Bible, and everything in between. They soon became engaged. But Lincoln grew nervous about marriage, and he quickly broke off the engagement. He fell into a deep depression. His friends removed razors from his room, fearing that he would kill himself. But when Lincoln’s friend Joshua Speed entered into a happy marriage, Abraham began to reconsider the marriage question.

Lincoln got married to Mary in one day. There was no glamorous party either. This has led to speculation that Abe had sex with Mary before the wedding, and that it might have been a shotgun marriage. However, there is no hard proof for this claim. According to the wedding’s best man, Lincoln looked like he was going to the slaughter. The 33-year-old became a husband in November of 1842. About nine months later, he had his first child, named Robert.

Historians debate the quality of Lincoln’s marriage. To some historians, he suffered in an abusive relationship. Mary struck him in the face, and threw potatoes and other objects at him. She hit him with stove wood. She chased him out of the house with a knife. However, these claims are of dubious quality because their source, Abraham’s law partner Billy Herndon, hated Mary. Billy might have deliberately exaggerated the marriage’s problems. Other historians think that Lincoln had a very happy marriage. In this view, the couple had an intimate physical and personal relationship.

Mary did have a neurotic streak, however. She grew especially anxious in Lincoln’s absence. She was terrified of thunderstorms and dogs. She suffered from migrations and exhaustion. Even when Abraham was home, he was often moody and distant. He tended to be absorbed by public life, and was not a very warm husband or father.

The Lincolns had a second son, named Edward, in 1846.

Law career

Lincoln, despite his lack of formal education, proved to be an adept lawyer. He spoke plainly, and was able to convince juries. He won them over through the warmth of his personality, as well as his likable self-deprecating humor. He gained a reputation for personal integrity, earning the famous nickname Honest Abe.

Like the man himself, Lincoln’s law office was plain and simple. He kept his important papers in his iconic stovepipe hat. His partner, Billy Herndon, complained about Lincoln’s casualness. Abe would relax himself on the couch and read aloud, much to Billy’s annoyance. But Lincoln insisted that reading aloud helped him retain information better.

As his law practice grew, Lincoln was able to buy a house in 1844 for the price of $1,500.

National debut

Abraham Lincoln made his triumphant entry into America’s national politics in 1846. He won a Whig Party nomination for a seat in Congress. Now in his 30s, Lincoln was enthralled by political life in Washington. So did his wife. There, Abraham experienced his first in-depth encounter with slavery. On his commute to the Capitol, he witnessed slave functions. Women and men were sold off like cattle. Lincoln, a firm believer in America’s ideals of liberty and quality, was taken back by the horrors of the human trafficking. He proposed a referendum to end this abuse, but it won almost no support. After a single term, he found himself back in Illinois.

Being out of politics thrust Lincoln into intense periods of depression. This was made worse by personal problems. Although Abraham was hardly known to hold grudges, he did possess a deep hatred of his father. In 1849, Thomas Lincoln asked to see his son one last time on this Earth. Abraham, who had not forgotten his childhood beatings, refused. Nor did he attend his detested father’s funeral.

Abraham suffered further tragedy when his four-year-old son Edward died of tuberculosis. Mary became pregnant again, and their third son Willie was born in 1850. A fourth child, named Tad, appeared in 1853. Lincoln, once a distant father, now became an indulgent parent. “It is my pleasure that my children are free and happy, unrestrained by parental tyranny,” Lincoln reflected. “Love is the chain to bind a child to his parents.”

Bleeding Kansas

Despite these personal calamities, the idealistic Lincoln kept his eye on politics. In 1854, he seized another chance to break into the national spotlight. This time, the issue would again be slavery. At the South’s instigation, Congress voted to make the large federal territories of Kansas and Nebraska, which had formerly been free, to become open to slavery. Lincoln, like many Northerners, was outraged. Under the Three Fifths Compromise, the slave-holding South possessed political power from their population of enslaved people. Expansion of slavery meant a greater representation in the federal government, at the expense of the largely free North. On moral grounds, Lincoln denounced the institution of slavery. “We called the maxim ‘all men are created equal’ a self-evident truth. Now we are so greedy to be masters, we called it a self-evident lie,” he remarked in 1854.

But Lincoln also had political motivations. Many Northerners feared the expansion of slavery, because they themselves did not want to see black people. Racism was pervasive, even in the North. Even Lincoln himself did not feel the slaves to be equal to whites. He did not think blacks should vote, hold office, sit on juries, or intermarry with whites. Lincoln had his own solution to slavery. He supported paying slaveowners to free their slaves, and then voluntarily repatriating the blacks back to Africa.

Lincoln-Douglas debates

Lincoln’s moderate opposition to slavery earned him massive popularity in the North. Northerners opposed to the expansion of slavery formed a new political party: the Republicans.

In 1858, Lincoln ran as a Republican candidate for the Senate. He challenged Illinois Democrat Stephen Douglas, who wanted popular sovereignty to determine the fate of slavery. The debates between the two men became some of the most iconic in American history.

“A house divided against itself cannot stand,” Lincoln declared. “I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. It will become all one things or all the other.”

By this time, the issue of slavery had already been the cause of political violence between its opponents and supporters. Douglas appeared to have all the advantages. He had a deep baritone voice. He spoke rapidly, with great energy. Lincoln had a high, piercing voice; he lacked his opponent’s onstage presence. He awkwardly bent his knees as a means of emphasis. But despite Lincoln’s awkwardness, the logic of his arguments proved persuasive to many people. He had fine rapport with the crowd.

Lincoln’s debates with Douglas centered on one of America’s most enduring questions: race. Were blacks entitled to the protection of America’s Founding documents? Douglas argued no. Douglas felt that America’s government was intended for civilized white people, and not for the barbarous blacks and Indians. But Lincoln, in a master stroke of political rhetoric, recast the debate in stark moral terms. The future president insisted that slavery and democracy were incompatible, unfavorably comparing the former institution to the divine right of kings.

When Democrats won a majority in the state legislature, Douglas managed to keep his seat. Lincoln retreated back to his legal office, but he knew he had left a lasting mark on the nation.

Election of 1860

Thanks to the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln was catapulted into national stardom. There were talks of his becoming president in the next election. Initially, Lincoln did not take these presidential rumors seriously. But in the coming months, his mood changed.

In 1860, he began touring the nation. Lincoln shocked his audiences with his odd-looking appearance. He was tall and thin. He had disproportionately large hands and big floppy ears. Even Lincoln regarded himself as an ugly person. When a rival called him two-faced, he humorously replied, “If I had another face, do you think I’d wear this one?”

But when the crowds heard Lincoln speak, they were absolutely mesmerized. His anti-slavery speeches were well-received in New York, and was even compared to St. Paul. Many of Lincoln’s supporters began to craft an image of him as a humble, self-made American man from the frontier. Although he hated his farm life, it was good politics for him.

The Republicans held their national convention in Chicago, although Lincoln was not the front runner. However, many delegates felt he was the most electable, because of his moderate stance on slavery.

Lincoln managed to narrowly win the election, with almost zero support from the slave states. The South immediately began talks of armed revolt. Lincoln tried to allay Southern fears that he would not touch slavery in its existing form, but it fell on deaf ears.

Southern Secession

Just before Christmas, South Carolina seceded from the Union. State and state quickly followed. By January, a Northern ship of troops traveled to Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. It was fired upon by the Southern Rebels. The outgoing president, James Buchanan, stood by helplessly, unsure what to do. The nation’s eyes now turned to Lincoln.

Lincoln believed the South’s anger would cool down. However, the new president made it clear that he would not tolerate secession.

Before the election, the president-elect began to focus on improving his appearance. He received advice from an 11-year-old girl named Grace Bedell, who urged him to grow out his beard. The now-iconic beard immediately made Lincoln appear more mature and statesman-like. It disguised the thinness of his face.

Lincoln left for Washington out of Springfield, where he was greeted by his friends before departure. A man who lacked any administrative experience whatsoever, he was now preparing to govern a country at war with itself.

Security was heavy, as the Lincoln family made their two-week journey from Illinois to the capital. En route, the president-to-be learned of the South’s secession. The Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, predicted a long and bloody war. Death threats from Baltimore forced Lincoln to be secretly smuggled into Washington by night. This unpresidential entry made him look like a coward. Because of this humiliation, he became very unconcerned about his own safety for the remainder of his presidency.

Fort Sumter

Having writing his inaugural speech ahead of time, Lincoln continued to cling to the hope of national reconciliation. He appealed to “the better angels of our nature” and “the mystical chords of memory.” But the speech was deemed an aggressive act of war by the South.

That same day, Lincoln received news that Fort Sumter would require reinforcements. He had to decide whether to send in federal troops, or to cede it to the Confederacy.

Lincoln was a man of peace. He did not want war. But he could not give up the fort. He agonized over the decision for many days. Finally, he decided in favor of providing provisions, but not troops. If there would be war, he reasoned, the South would have to fire the first shot. That is exactly what happened on April 12, 1861. The Rebels fired upon the fort, and forced its surrender. Civil war had begun.

News was greeted with euphoria in the North, which was eager to crush the slave-holding South. But the president was hardly gleeful, recognizing that the South’s troops would be a formidable fighting force. He moved quickly, calling up troops and suspending habeas corpus to arrest Southern sympathizers. He ordered a blockade of Southern ports.

Lincoln refused to recognize the legitimacy of secession. He saw it as unconstitutional. The president was careful not to make abolitionism an official goal of the war. He instead cast it as a war to preserve the Union. Because of this, four slave-owning border states remained loyal to the Union. These were Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. “I hope to have God on my side, but I have to have Kentucky,” Lincoln joked. He feared that if the border states defected to the Southern cause, the Northern cause would be lost.

Bull Run

The president wanted to quickly strike at the South, while the North’s morale was still high. He proposed an attack on a vital rail junction in northern Virginia, at Manassas, near Bull Run.

Northern generals warned that their troops were too inexperienced. But the president was confident that the South’s troops were equally unseasoned.

In July of 1861, General Irvin McDowell reluctantly led a Union Army against the Rebels near Manassas. But the Northerners were crushed, and forced into a humiliating retreat. Lincoln suffered his first taste of defeat.

The president replaced Northern command with a promising Union general named George B. McClellan. Known as Little Napoleon, he had an ego to match. Although a superb trainer, he did not wage a single campaign after a full six months. McClellan hated the president’s interference, regarding Lincoln as woefully uninformed in military affairs. The difficult general even snubbed Lincoln to his face. Lincoln wanted the numerically superior Union forces to overwhelm the South on all fronts. But McClellan was opposed. The two men clashed bitterly.

“If McClellan is not going to use the Army of the Potomac, I would like to borrow it,” Lincoln joked scornfully.

Ulysses S. Grant

In sharp contrast to McClellan’s inaction, one Union general shone gloriously in the Western front. His name was Ulysses S. Grant, and he certainly matched the grandiosity of his Homeric hero namesake.

The president took an immediate liking to Grant. Although Grant received criticism for his ruthless tactics at Shiloh, Lincoln was more than willing to overlook any flaws to achieve a speedy victory.

It gave him some optimism. But personal tragedy would strike Lincoln after his son Willie died of typhoid. For two weeks, the president canceled his professional duties to attend to his son. The death of Willie caused the president to burst into tears. But Lincoln could afford little time for mourning.

Emancipation Proclamation

In the West, Grant got bogged down. In the East, McClellan finally made his long-awaited advance toward Richmond, but was harshly driven back by Lee’s Confederates.

Lincoln felt that a drastic change had to be made. To hurt the South, he began to promise freedom to the South’s slave population. There were four million slaves, who were vital to the Confederacy’s war effort. Although Lincoln had earlier felt that the Constitution did not authorize the president to abolish slavery, the Civil War changed those dynamics entirely. As commander-in-chief, he was now at liberty to take extra-legal measures. It also matched his own desire to liberate the slaves for moral reasons.

Lincoln penned his famous Emancipation Proclamation. It pledged that any state still in rebellion by 1863 would have their slaves freed. The president was cautious not to offend the border states, and did not free any slaves in the Union-held territories. But it did encourage many Southern slaves to flee the plantation.

However, it must be noted that Lincoln’s emancipation was not fully well-intentioned. He genuinely viewed blacks as inferiors, and still wanted to send them back to Africa. He especially spoke this way to curry favor with white Northern abolitionists. The president didn’t think that a biracial society was a realistic possibility, despite his principled opposition to slavery.

“If I could save the Union without freeing a single slave, I would do it,” Lincoln explained in August of 1862. “And I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it.”

Antietam

Finally, Lincoln got the victory he was waiting for. McClellan just barely defeated Lee’s forces at the Battle of Antietam, Maryland in September of 1862. Five days later, the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The North’s reaction was varied. Abolitionists and black leaders were thrilled, but angry whites rioted over fear that the former slaves would supplant their jobs. Many Union soldiers, who didn’t care about blacks, deserted the cause. With the Emancipation Proclamation, the Civil War went from a war against insurrection into one against slavery. Lincoln solidified his legacy as the Great Emancipator.

The president lost patience with McClellan, and fired him. He hired a new general, named Ambrose Burnside. However, Burnside did not fear much better. He led a suicidal charge at Fredericksburg, in what became the Union’s worst defeat of US history. Burnside was replaced by General Joseph Hooker, who led the Eastern army into yet another disaster at Chancellorsville.

These defeats left Lincoln ghostlike and broken, according to his staff. But the president never considered giving up. He believed that the American experiment in self-government was far too great to surrender. It was too promising to the rest of the world.

“New birth of freedom”

Lincoln was now forced to rely on black soldiers. Although initially skeptical, the president quickly realized that they were a fearsome fighting force. 180,000 black Americans would fight to save the Union. Their bravery changed Lincoln’s attitudes toward black people and civil rights.

With many blacks dying bravely for the Union, President Lincoln quietly abandoned all talks of repatriating them to Africa. Over the course of 1863, the Civil War finally turned in the North’s favor.

At Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, over three days of bloody fighting that left 40,000 dead and wounded, Robert E. Lee was dealt a deadly defeat. News of the Union’s triumph reached Lincoln on the Fourth of July, the same day that Grant seized Vicksburg, Mississippi.

President Lincoln was invited to give a speech at a veteran cemetery. This became his famous Gettysburg Speech. In just ten sentences, and about two minutes, Lincoln distilled the essence of the Union’s crusade for liberty. Photographs captured the glorious scene of Lincoln speaking, dressed in top hat and beard.

Today, the Gettysburg Address is considered one of the finest speeches in all of American oratory.

Election of 1864

Lincoln entered his re-election year with soaring popularity in the North. But he knew that his chances were tied to the war’s fickle outcomes. So when trouble brewed in the East, he brought in his favorite Western general to bring victory.

Grant knew that the only way to win was to relentlessly attack. He chased Lee across Virginia. The costs were truly astonishing. In just two weeks, Grant lost a third of his 100,000 men. Northern civilians were horrified by these unsustainable casualties. Even Lincoln’s wife saw Grant as a ruthless butcher.

The horrifying bloodshed took a harsh toll on Lincoln, but he continued with the war anyway. Despite pressure from the North, the president refused to accept anything short of unconditional surrender and the abolition of slavery.

Just in time, the election tide turned in Lincoln’s favor. General William Sherman seized Atlanta. The North burst into patriotic fervor, and Lincoln defeated his old general McClellan in a landslide electoral victory.

With Grant and Sherman shoring up victory, the newly re-elected President Lincoln used his influence to abolish slavery permanently. Because the Emancipation Proclamation had been passed as a wartime measure, Lincoln now urged Congress to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery forever.

The president offered peace to the Rebels if they agreed to lay down their arms and end slavery. He even offered compensation for the slaveowners, but they obstinately refused.

End of the war

In his Second Inaugural Address, the philosophically-minded president pondered why God would allow such evil and destruction. Lincoln came to the conclusion that the Civil War was divine retribution for the sin of slavery over the past two centuries.

Having won the Civil War, the great president toured the war-torn Confederate capital at Richmond. Black crowds gathered around him in praise, while the bitter white Southerners refused to greet Lincoln. “Thank God I have lived to see this,” Lincoln said. “Now the nightmare is over.”

By early April of 1865, the Civil War was all but finished. Freedom had prevailed. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. On April 11, he called for clemency toward the Rebels, and urged for black suffrage. “That means nigger citizenship,” a seething John Wilkes Booth complained. “That’s the last speech he will ever make.”

Booth, who came from a slaveholding family in Maryland, was one of America’s favorite actors. But he was also a virulent fanatic for the Confederate cause. He had already been planning to kidnap the president, but now, he was ready to outright murder him.

Lincoln had a premonition of the assassination. He had a strange dream about a dead president in a coffin. This would become a real-life nightmare with his own death soon after.

Assassination

It was April 14, Good Friday. On a carriage ride through Washington, Lincoln was uncharacteristically cheerful. It was a lovely spring day.

Lincoln told his wife about how they had been miserable from Willie’s death and the war. He talked about what they could do to celebrate in times of peace.

That night, the First Couple went to the theater with a senator’s daughter, Clara Harris, as well as her finance named Major Henry Rathbone. At Ford’s Theater, the performance of Our American Cousin had already started. The play stopped in the middle of the performance, as the Lincolns arrived. “Hail to the Chief” was played. The audience rose and cheered.

Meanwhile, Booth was hatching his conspiracy. He planned to go to the theater and murder Lincoln at 10 o’clock. He instructed three conspirators to simultaneously eliminate Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward.

Booth, who was well-known to the theater’s staff, had little trouble breaking into the president’s box. The policemen guarding Lincoln had gone down to watch the play.

Mary leaned in toward her husband affectionately. She put her arm through his, and smiled up at him. “What will Miss Harris think of my hanging on to you?” she asked playfully. “She wouldn’t think a thing about it,” he replied suavely. Little did the president know, it would be his last conversation on this Earth.

As laughter broke out in the third act, Booth walked up behind Lincoln. He pointed a Derringer at the back of the president’s head. Suddenly, a gunshot was heard. As Lincoln’s corpse slumped forward, Major Rathbone tried to seize the intruder, but Booth stabbed him. The rogue actor jumped down to the stage, and shouted, “Sic semper tyrannis.” In Latin, this means, “Thus always to tyrants,” a reference to Brutus’ killing of Caesar in the ancient Roman Republic. Booth then escaped through a back exit.

“They have shot the president,” Mary screamed from the box. An Army surgeon, Dr. Charles Leal, rushed to the shot president and gave artificial respiration. Lincoln’s heart was still beating. Soon, four doctors rallied around Lincoln. They carried him to the nearest bed.

As onlookers screamed from the outside, the doctors were summoned into a boarding house across the street. The bed was too small for Lincoln, who had to be laid diagonally. The doctors all agreed that the wound was fatal.

Mary Lincoln screamed hysterically for her shot husband. Finally, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered her to leave. The president clung on to dear life until 7:22 the next morning, on April 15. He was aged 56. “Now, he belongs to the ages,” Stanton declared.

Funeral

The deceased president’s body was carried back to the White House. The occasion would be remembered as Black Easter.

Having been killed on Good Friday, many Northerners turned Lincoln into a Christ-like martyr. Blacks in the South were especially grief-stricken. But white Southerners saw it as divine vengeance against the tyrannical Lincoln.

Twelve days after Lincoln’s assassination, federal officials tracked down Booth to a tobacco farm in Virginia, where the criminal was shot dead. Four of his conspirators, including one who wounded Seward, were tried and hanged.

Back in Washington, Lincoln’s body laid for three days at the capital. Hundreds of thousands walked by the coffin, and looked at Lincoln’s bruised face.

A week after the assassination, a nine-car funeral train left the Capitol with Lincoln’s body back to Illinois. Crowds were dangerously large in the desire to see the body. In Springfield, Lincoln was laid to rest.

Legacy

Lincoln is widely considered one of America’s greatest presidents.

Had he survived, the benevolent man might have secured greater civil rights in the post-Reconstruction South. There might not have been a need for the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s. Lincoln’s successors were unable to fill his shoes, and the ignominious rise of Jim Crow in the post-war South remains a stain on America’s liberty-loving history.

But still, he achieved more than enough in a single term than most other presidents could dream of. He did the unthinkable. He kept the nation together, and oversaw the much-needed end of slavery. Through his unsurpassed leadership, America’s experiment in republican government remains alive and intact even to this very day.

Learn More

Lincoln is my favorite US president!